Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hematologic Disorders

Procuring Blood and Blood Products

Procuring Blood and Blood Products

BLOOD DONATION

To

protect both the donor and the recipients, all prospective donors are examined

and interviewed before they are allowed to donate their blood. The intent of

the interview is to assess the general health status of the donor and to

identify risk factors that might harm a recipient of the donor’s blood. Donors

should be in good health and without any of the following:

•

A history of viral hepatitis at any time in the

past, or a his-tory of close contact with a hepatitis or dialysis patient

within 6 months

•

A history of receiving a blood transfusion or an

infusion of any blood derivative (other than serum albumin) within 6 months

•

A history of untreated syphilis or malaria, because

these dis-eases can be transmitted by transfusion even years later. A person

who has been free of symptoms and off therapy for 3 years after malaria may be

a donor.

•

A history or evidence of drug abuse in which

substances were self-injected, because many intravenous/injection drug users

are hepatitis carriers and because the risk for human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV) is high in this group

•

A history of possible exposure to HIV; the

population at risk includes people who engage in anal sex, people with multiple

sexual partners, intravenous/injection drug users, sexual partners of people at

risk for HIV, and people with hemophilia

•

A skin infection, because of the possibility of

contami-nating the phlebotomy needle, and subsequently the blood itself

•

A history of recent asthma, urticaria, or allergy

to medica-tions, because hypersensitivity can be transferred passively to the

recipient

•

Pregnancy within 6 months, because of the

nutritional de-mands of pregnancy on the mother

•

A history of tooth extraction or oral surgery

within 72 hours, because such procedures are frequently associated with

tran-sient bacteremia

•

A history of exposure to infectious disease within

the past 3 weeks, because of the risk of transmission to the recipient

•

Recent immunizations, because of the risk of

transmitting live organisms (2-week waiting period for live, attenuated

organisms; 1 month for rubella; 1 year for rabies)

•

A history of recent tattoo, because of the risk of

blood-borne infections (eg, hepatitis, HIV)

•

Cancer, because of the uncertainty about

transmission of the disease

•

A history of whole blood donation within the past

56 days

Potential

donors should be asked whether they have consumed any aspirin or

aspirin-containing medications within the past 3 days. Although aspirin use does

not render the donor ineligible, the platelets obtained would be dysfunctional

and therefore not useful. Aspirin does not affect the RBCs or plasma obtained

from the donor.

All

donors are expected to meet the following minimal re-quirements:

•

Body weight should exceed 50 kg (110 pounds) for a

stan-dard 450-mL donation. Donors weighing less than 50 kg do-nate

proportionately less blood. People younger than 17 years of age are

disqualified from donation.

•

The oral temperature should not exceed 37.5°C (99.6°F).

•

The pulse rate should be regular and between 50 and

100 beats per minute.

•

The systolic arterial pressure should be 90 to 180

mm Hg, and the diastolic pressure should be 50 to 100 mm Hg.

•

The hemoglobin level should be at least 12.5 g/dL

for women and 13.5 g/dL for men.

Directed Donation

At

times, friends and family of a patient wish to donate blood for that person.

These blood donations are termed directed dona-tions. These donations are not

any safer than those provided by random donors, because directed donors may not

be as willing to identify themselves as having a history of any of the risk

factors that disqualify a person from donating blood.

Standard Donation

Phlebotomy

consists of venipuncture and blood withdrawal. Standard precautions are used.

Donors are placed in a semi-recumbent position. The skin over the antecubital

fossa is carefully cleansed with an antiseptic preparation, a tourniquet is

applied, and venipuncture is performed. Withdrawal of 450 mL of blood usually

takes less than 15 minutes. After the needle is removed, donors are asked to

hold the involved arm straight up, and firm pressure is applied with sterile

gauze for 2 or 3 minutes or until bleeding stops. A firm bandage is then

applied. Donors remain recumbent until they feel able to sit up, usually within

a few min-utes. Donors who experience weakness or faintness should rest for a

longer period. Donors then receive food and fluids and are asked to remain

another 15 minutes.

Donors

are instructed to leave the dressing on and to avoid heavy lifting for several

hours, to avoid smoking for 1 hour, to avoid drinking alcoholic beverages for 3

hours, to increase fluid intake for 2 days, and to eat a healthy meals for 2

weeks. Specimens from this donated blood are tested to detect in-fections and

to identify the specific blood type (see later discussion).

Autologous Donation

A

patient’s own blood may be collected for future transfusion; this method is

useful for many elective surgeries where the po-tential need for transfusion is

high (eg, orthopedic surgery). Pre-operative donations are ideally collected 4

to 6 weeks before surgery. Iron supplements are prescribed during this period

to prevent depletion of iron stores. Occasionally, erythropoietin (epoetin-alfa

[Epogen, Procrit]) is given to stimulate erythro-poiesis to ensure that the

donor’s hematocrit remains high enough to be eligible for donation. Typically,

1 unit of blood is drawn each week; the number of units obtained varies with

the type of surgical procedure to be performed (ie, the amount of blood

anticipated to be transfused). Phlebotomies are not per-formed within 72 hours

of surgery. Individual blood compo-nents can also be collected.

The

primary advantage of autologous transfusions is the pre-vention of viral infections

from another person’s blood. Other ad-vantages include safe transfusion for

patients with a history of transfusion reactions, prevention of

alloimmunization, and avoid-ance of complications in patients with

alloantibodies. The policy of the American Red Cross requires autologous blood

to be trans-fused only to the donor. If the blood is not required, it can be

frozen until the donor needs it in the future (for up to 10 years). The blood

is never returned to the general donor supply of blood products to be used by

someone else.

The

disadvantage of autologous donation is that it may be per-formed even when the

likelihood that the anticipated procedure will necessitate a transfusion is

small. Needless autologous dona-tion is expensive, takes time, and uses

resources inappropriately. Moreover, in an emergency situation, the autologous

units avail-able may be inadequate, and the patient may still require

additional units from the general donor supply.

Contraindications

to donation of blood for autologous transfusion are acute infection, severely

debilitating chronic disease, hemoglobin level less than 11 g/dL, hematocrit

less than 33%, unstable angina, and acute cardiovascular or cere-brovascular

disease. A history of poorly controlled epilepsy may be considered a

contraindication in some centers. Patients with cancer may donate for

themselves.

Intraoperative Blood Salvage

This

transfusion method provides replacement for patients who are unable to donate

before surgery and for those undergoing vas-cular, orthopedic, or thoracic

surgery. During a surgical proce-dure, blood lost into a sterile cavity (eg,

hip joint) is suctioned into a cell-saver machine. The RBCs are washed, often

with saline solution, and then returned to the patient as an intravenous in-fusion.

Salvaged blood cannot be stored, because bacteria cannot be completely removed

from the blood.

Hemodilution

This

transfusion method is initiated before or after induction of anesthesia. About

1 or 2 units of blood are removed from the pa-tient through a venous or

arterial line and simultaneously replaced with a colloid or crystalloid

solution. The blood obtained is then reinfused after surgery (Kreimeier &

Messmer, 2002). The advan-tage of this method is that the patient loses fewer

RBCs during surgery, because the added intravenous solutions dilute the

con-centration of RBCs and lower the hematocrit. Patients who are at risk for

myocardial injury, however, should not be further stressed by hemodilution.

COMPLICATIONS OF BLOOD DONATION

Excessive

bleeding at the donor’s venipuncture site is sometimes caused by a bleeding

disorder in the donor but more often results from a technique error: laceration

of the vein, excessive tourniquet pressure, or failure to apply enough pressure

after the needle is withdrawn.

Fainting

is common after blood donation and may be related to emotional factors, a

vasovagal reaction, or prolonged fasting be-fore donation. Because of the loss

of blood volume, hypotension and syncope may occur when the donor assumes an

erect position. A donor who appears pale or complains of faintness should

im-mediately lie down or sit with head lowered below the knees; he or she

should be observed for another 30 minutes.

Anginal

chest pain may be precipitated in patients with un-suspected coronary artery

disease. Seizures can occur in donors with epilepsy, although the incidence is

very low. Both angina and seizures require further medical evaluation.

Many

people have the misconception that donating blood can cause AIDS and other

infections. Potential donors need to be ed-ucated that the equipment used in

donation is sterile, a closed sys-tem, and not reusable; they are at no risk

for acquiring such infections from donating blood.

BLOOD PROCESSING

Samples

of the unit of blood are always taken immediately after donation so that the

blood can be typed and tested. Each do-nation is tested for antibodies to HIV 1

and 2, hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human

T-cell lymphotropic virus, type I (anti-HTLV-I/II). The blood is also tested

for hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAG) and for syphilis. Negative reactions

are required for the blood to be used, and each unit of blood is labeled to

certify the results. A new testing method, using nucleic acid amplification testing

(NAT), has increased the ability to detect the presence of HCV and HIV

infection, because it directly tests for genomic nucleic acids of the virus

itself, rather than for the presence of antibodies to the virus (Korman, Leparc

& Benson, 2001). This testing significantly shortens the “window” of

inability to detect HIV and HCV from a donated unit, further ensuring the

safety of the blood. Blood is also screened for CMV; if it tests positive for

CMV, it can still be used, except in recipients who are neg-ative for CMV and

who are immunocompromised (eg, BMT or PBSCTrecipients).

Equally

important to viral testing is accurate determination of the blood type. More

than 200 antigens have been identified on the surface of RBC membranes. Of

these, the most important for safe transfusion are the ABO and Rh systems. The

ABO system identifies which sugars are present on the membrane of an

indi-vidual’s RBCs: A, B, both A and B, or neither A nor B (type O). To prevent

a significant reaction, the same type of RBCs should be transfused. Previously,

it was thought that in an emergency sit-uation in which the patient’s blood

type was not known, type O blood could be safely transfused. This practice is

no longer ad-vised by the American Red Cross.

The Rh

antigen (also called D) is present on the surface of RBCs in 85% of the

population (Rh-positive). Those who lack the D antigen are called Rh-negative.

RBCs are routinely tested for the D antigen as well as ABO. Patients should

receive PRBCs with a compatible Rh type.

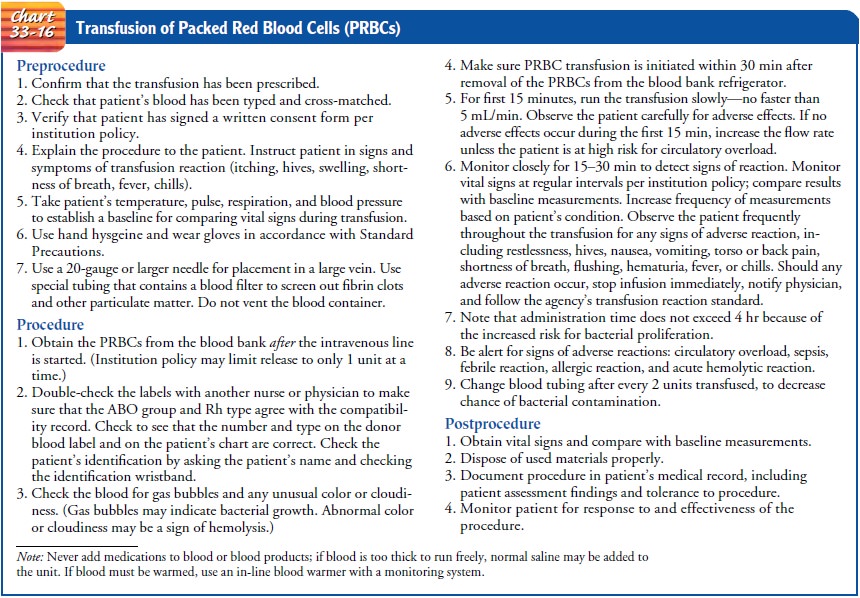

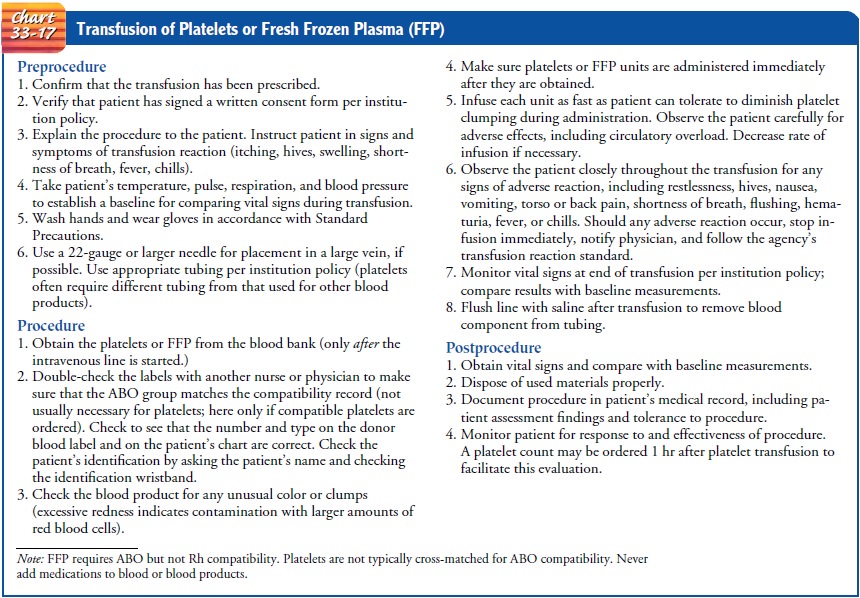

TRANSFUSION

Administration

of blood and blood components requires knowl-edge of correct administration

techniques and possible complica-tions. It is very important to be familiar

with the agency’s policies and procedures for transfusion therapy. Methods for

transfusing blood components are presented in Charts 33-16 and 33-17. Potential

complications of transfusion follow.

Setting

Although

most blood transfusions are performed in the acute care setting, patients with

chronic transfusion requirements often can receive transfusions in other

settings. Free-standing infusion cen-ters, ambulatory care clinics, a

physician’s office, and even the home may be appropriate settings for

transfusion. Typically, pa-tients who need chronic transfusions but are

otherwise stable physically are appropriate candidates for outpatient therapy.

Ver-ification and administration of the blood product are performed much as in

a hospital setting. Although most blood products can be transfused in the

outpatient setting, the home is typically lim-ited to transfusions of PRBCs and

factor components (eg, factor VIII for patients with hemophilia)

Pretransfusion Assessment

PATIENT HISTORY

Patient history is an important component of the pretransfu-sion assessment to determine the history of previous transfu-sions as well as previous reactions to transfusion. The history should include the type of reaction, its manifestations, the in-terventions required, and whether any preventive interventions were used in subsequent transfusions. It is important to assess the number of pregnancies a woman has had, because an in-creased number can increase her risk for reaction due to anti-bodies developed from exposure to fetal circulation. Other concurrent health problems should also be noted, with careful attention to cardiac, pulmonary, and vascular disease.

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT

A

systematic physical assessment and measurement of baseline vital signs are

important before transfusing any blood product. The res-piratory system should

be assessed, including careful auscultation of the lungs and for use of

accessory muscles. Cardiac system as-sessment should include careful inspection

for any edema as well as other signs of cardiac failure (eg, jugular venous

distention). The skin should be observed for rashes, petechiae, and

ecchy-moses. The sclera should be examined for icterus. In the event of a

possible transfusion reaction, a comparison of findings can help differentiate

between types of reactions.

Patient Teaching

Reviewing

the signs and symptoms of a potential transfusion re-action is crucial for

patients who have not received a transfusion be-fore. Even for those patients

who have received prior transfusions, a brief review of signs and symptoms of

potential transfusion reac-tions is advised. Signs and symptoms of a possible

reaction include fever, chills, respiratory distress, low back pain, nausea,

pain at the intravenous site, or anything “unusual.” Although a thorough

re-view is very important, it is also important to reassure the patient that

the blood is carefully tested against the patient’s own blood (cross-matched)

to diminish the likelihood of any untoward reac-tion. Such assurance can be

extremely beneficial in allaying anxi-ety. Similarly, it can be useful to

mention again the very low possibility of contracting HIV from the transfusion;

this fear per-sists among many people.

Related Topics