Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hematologic Disorders

Pathophysiology of the Hematologic System

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

OF THE HEMATOLOGIC SYSTEM

Most

hematologic diseases reflect a defect in the hematopoietic, he-mostatic, or RES

systems. The defect can be quantitative (eg, in-creased or decreased production

of cells), qualitative (eg, the cells that are produced are defective in their

normal functional capac-ity), or both.

Gerontologic Considerations

In

elderly patients, a common problem is decreased ability of the bone marrow to

respond to the body’s need for blood cells (RBCs, WBCs, and platelets). This

inability is a result of many factors, in-cluding diminished production of the

growth factors necessary for hematopoiesis by stromal cells within the marrow

or a diminished response to the growth factors (in the case of erythropoietin).

When an elderly person needs more blood cells (eg, WBCs in infection, RBCs in

anemia), the bone marrow may not be able to increase production of these cells

adequately.Leukopenia (a de-creased

number of circulating WBCs) or anemia can result. In the elderly, the bone

marrow may be more susceptible to the myelo-suppressive effects of medications.

Anemia

is the most common hematologic condition affecting elderly patients; with each

successive decade of life, the incidence of anemia increases. Anemia frequently

results from iron deficiency (in the case of blood loss) or from a nutritional

deficiency, partic-ularly folate or B12 deficiency or protein-calorie malnutrition;

it may also result from inflammation or chronic disease. Manage-ment of the

disorder varies depending on the etiology. Therefore, it is important to

identify the cause of the anemia rather than to consider it an inevitable

consequence of aging. Elderly people with concurrent cardiac or pulmonary

problems may not tolerate ane-mia very well, and a prompt, thorough evaluation

is warranted.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Many

hematologic conditions cause few symptoms. Therefore, the use of extensive

laboratory tests is often required to diagnose a hematologic disorder. For most

hematologic conditions, contin-ued monitoring via specific blood tests is

required because it is very important to assess for changes in test results

over time.

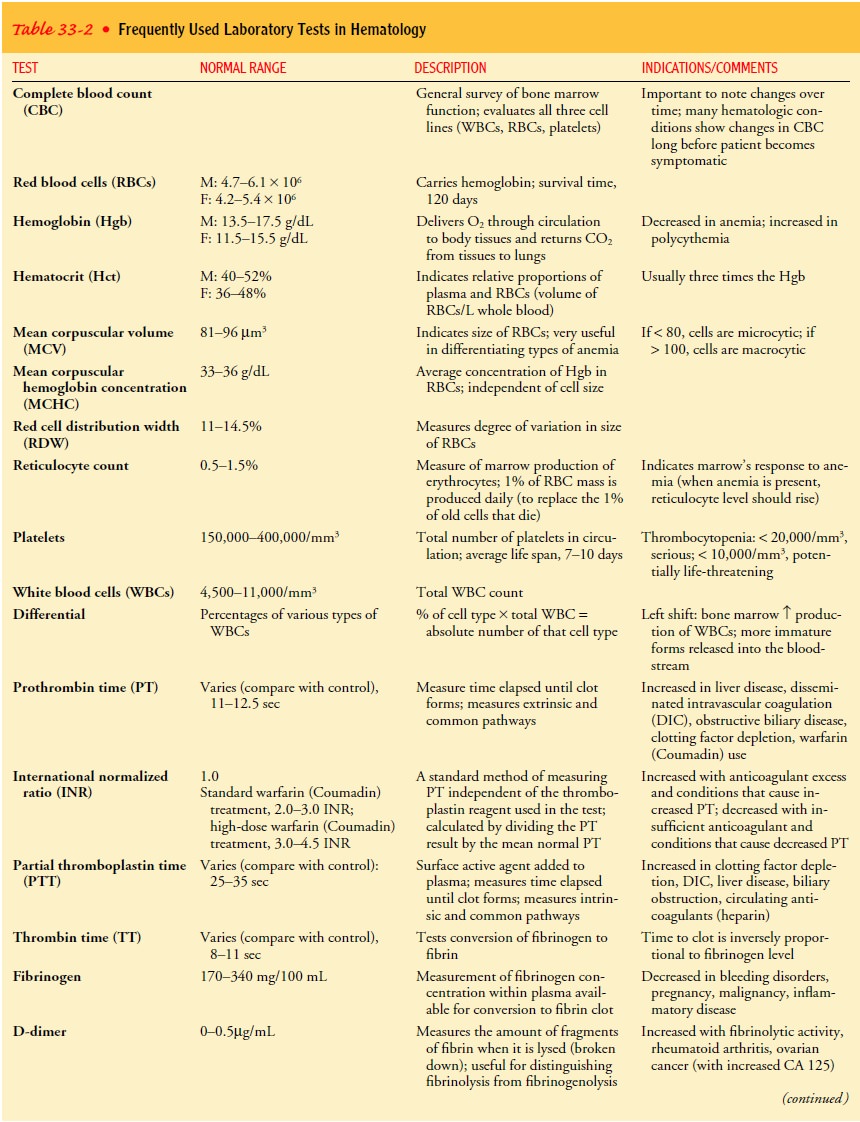

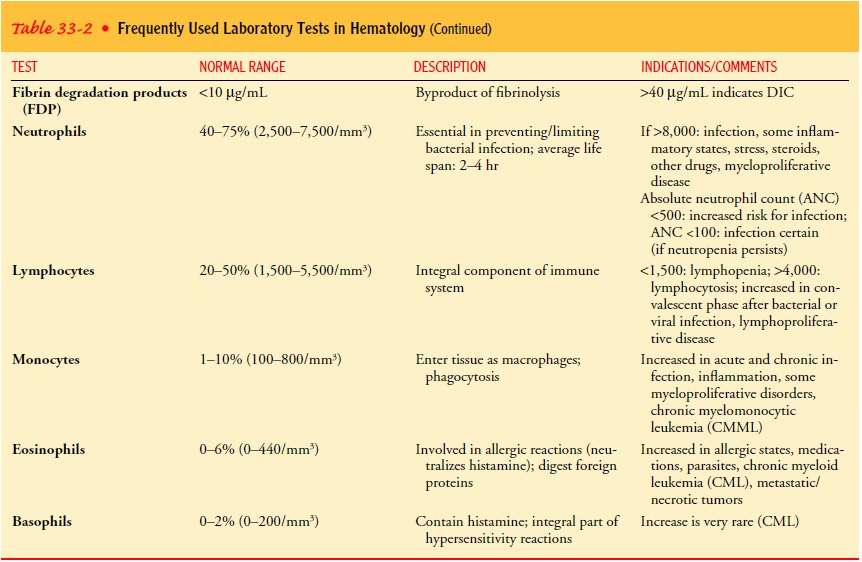

HEMATOLOGIC STUDIES

The

most common tests used are the complete blood count (CBC) and the peripheral

blood smear (Table 33-2). The CBC identifies the total number of blood cells

(WBCs, RBCs, and platelets) as well as the hemoglobin, hematocrit (percentage of blood consisting of RBCs), and RBC

indices. Because cellular morphology (shape and

appearance of the cells) is particularly important in most hematologic

disorders, the physician needs to examine the blood cells involved. This

process is referred to as the manual examination of the peripheral smear, which

may be part of the CBC. In this test, a drop of blood is spread on a glass

slide, stained, and examined under a microscope. The shape and size of the RBCs

and platelets as well as the actual appearance of the WBCs provides useful

information in identifying hematologic conditions. Blood for the CBC is

typically obtained by venipuncture.

BONE MARROW ASPIRATION AND BIOPSY

The

bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are crucial when addi-tional information is

needed to assess how an individual’s blood cells are being formed and to assess

the quantity and quality of each type of cell produced within the marrow. These

tests are also used to document infection or tumor within the marrow.

Normal

bone marrow is in a semifluid state and can be aspi-rated through a special

large needle. In adults, bone marrow is usually aspirated from the iliac crest

and occasionally from the sternum. The aspirate provides only a sample of

cells. Aspirate alone may be adequate for evaluating certain conditions, such

as anemia. However, when more information is required, a biopsy is also

performed. Biopsy samples are taken from the posterior iliac crest;

occasionally, an anterior approach is required. A mar-row biopsy shows the

architecture of the bone marrow as well as its degree of cellularity.

Most

patients need no more preparation than a careful expla-nation of the procedure,

but for some very anxious patients, an antianxiety agent may be useful. It is

always important for the physician or nurse to describe and explain to the

patient the pro-cedure and the sensations that will be experienced. The risks,

benefits, and alternatives are also discussed. A signed informed consent is

needed before the procedure is performed.

Before

aspiration, the skin is cleansed as for any minor surgery, using aseptic technique.

Then a small area is anesthetized with a local anesthetic through the skin and

subcutaneous tissue to the periosteum of the bone. It is not possible to

anesthetize the bone itself. The bone marrow needle is introduced with a stylet

in place. When the needle is felt to go through the outer cortex of bone and

enter the marrow cavity, the stylet is removed, a syringe is at-tached, and a

small volume (0.5 mL) of blood and marrow is as-pirated. Patients typically

feel a pressure sensation as the needle is advanced into position. The actual

aspiration always causes sharp but brief pain, resulting from the suction

exerted as the marrow is aspirated into the syringe; the patient should be

forewarned about this. Taking deep breaths or using relaxation techniques often

helps ease the discomfort.

If a

bone marrow biopsy is necessary, it is best performed after the aspiration and

in a slightly different location, because the mar-row structure may be altered

after aspiration. A special biopsy nee-dle is used. Because these needles are

large, the skin is punctured first with a surgical blade to make a 3- or 4-mm

incision. The biopsy needle is advanced well into the marrow cavity. When the

needle is properly positioned, a portion of marrow is cored out, using a twisting

or gentle rocking motion to free the sample and permit its removal within the

biopsy needle. Patients feel a pres-sure sensation but should not feel actual

pain. The nurse should instruct the patient to inform the physician if pain

occurs so that additional anesthetic can be administered.

The major hazard of either bone marrow aspiration or biopsy is a slight risk of bleeding and infection. The bleeding risk is some-what increased if the patient’s platelet count is low or if the patient has been taking a medication (eg, aspirin) that alters platelet function.

After the marrow sample is obtained, pressure is applied to the site for

several minutes. The site is then covered with a sterile dressing. Most

patients have no discomfort after a bone marrow aspiration, but the site of a

biopsy may ache for 1 or 2 days. Warm tub baths and use of a mild analgesic

(eg, acetaminophen) may be useful. Aspirin-containing analgesics should be avoided

because they can aggravate or potentiate any bleeding that may occur.

Related Topics