Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hematologic Disorders

Anemia - Management of Hematologic Disorders

Management of Hematologic Disorders

Commonly

encountered blood disorders are anemia, polycythe-mia, leukopenia and neutropenia, leukocytosis, lymphoma,

mye-loma, leukemia, and various

bleeding and coagulation disorders. Nursing management of patients with these

disorders requires skill-ful assessment and monitoring as well as meticulous

care and teach-ing to prevent deterioration and complications.

ANEMIA

Anemia,

per se, is not a specific disease state but a sign of an under-lying disorder.

It is by far the most common hematologic condi-tion. Anemia, a condition in

which the hemoglobin concentration is lower than normal, reflects the presence

of fewer than normal RBCs within the circulation. As a result, the amount of

oxygen delivered to body tissues is also diminished.

There

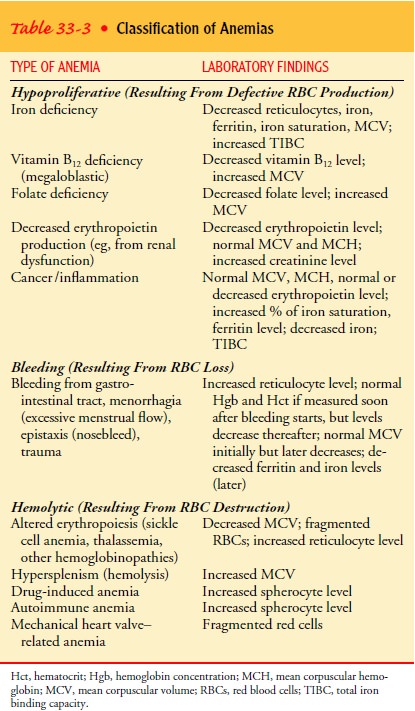

are many different kinds of anemia (Table 33-3), but all can be classified into

three broad etiologic categories:

•

Loss of RBCs—occurs with bleeding, potentially from

any major source, such as the gastrointestinal tract, the uterus, the nose, or

a wound

•

Decreased production of RBCs—can be caused by a

defi-ciency in cofactors (including folic acid, vitamin B12, and iron) required for

erythropoiesis; RBC production may also be reduced if the bone marrow is

suppressed (eg, by tumor, medications, toxins) or is inadequately stimulated

because of a lack of erythropoietin (as occurs in chronic renal disease).

•

Increased destruction of RBCs—may occur because of

an overactive RES (including hypersplenism) or because the bone marrow produces

abnormal RBCs that are then de-stroyed by the RES (eg, sickle cell anemia).

A

conclusion as to whether the anemia is caused by destruc-tion or by inadequate

production of RBCs usually can be reached on the basis of the following

factors:

•

The marrow’s ability to respond to the decreased

RBCs (as evidenced by an increased reticulocyte count in the circu-lating

blood)

•

The degree to which young RBCs proliferate in the

bone marrow and the manner in which they mature (as observed on bone marrow

biopsy)

• The presence or absence of end products of RBC destruction within the circulation (eg, increased bilirubin level, decreased haptoglobin level)

Classification of Anemias

Anemia

may be classified in several ways. The physiologic ap-proach is to determine

whether the deficiency in RBCs is caused by a defect in their production

(hypoproliferative anemia), by their destruction (hemolytic anemia), or by

their loss (bleeding).

In the

hypoproliferative anemias, RBCs usually survive nor-mally, but the marrow

cannot produce adequate numbers of these cells. The decreased production is

reflected in a low reticulocyte count. Inadequate production of RBCs may result

from marrow damage due to medications or chemicals (eg, chloramphenicol,

benzene) or from a lack of factors necessary for RBC formation (eg, iron,

vitamin B12, folic acid,

erythropoietin).

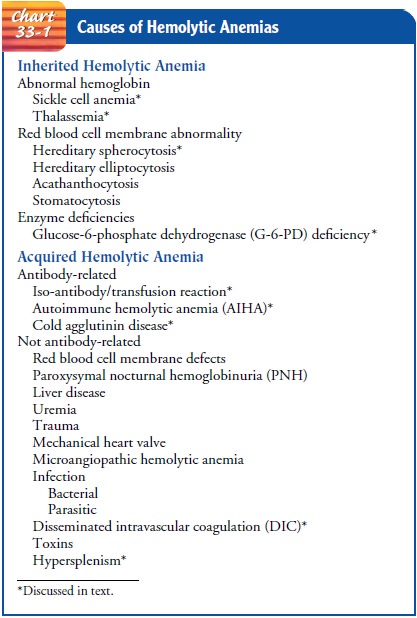

Hemolytic

anemias stem from premature destruction of RBCs, which results in a liberation

of hemoglobin from the RBC into the plasma. The increased RBC destruction

results in tissue hypoxia, which in turn stimulates erythropoietin production.

This increased production is reflected in an increased reticulocyte count, as

the bone marrow responds to the loss of RBCs. The released hemo-globin is

converted in large part to bilirubin; therefore, the biliru-bin concentration

rises. Hemolysis can result from an

abnormality within the RBC itself (eg, sickle cell anemia, glucose-6-phosphate

dehydrogenase [G-6-PD] deficiency) or within the plasma (eg, immune hemolytic

anemias), or from direct injury to the RBC within the circulation (eg,

hemolysis caused by mechanical heart valve). Chart 33-1 identifies the causes

of hemolytic anemia.

Clinical Manifestations

Aside

from the severity of the anemia itself, several factors influ-ence the

development of anemia-associated symptoms:

•

The speed with which the anemia has developed

•

The duration of the anemia (ie, its chronicity)

•

The metabolic requirements of the individual

•

Other concurrent disorders or disabilities (eg,

cardio-pulmonary disease)

•

Special complications or concomitant features of

the con-dition that produced the anemia

In general, the more rapidly an anemia develops, the more severe its symptoms. An otherwise healthy person can often toler-ate as much as a 50% gradual reduction in hemoglobin without pronounced symptoms or significant incapacity, whereas the rapid loss of as little as 30% may precipitate profound vascular collapse in the same individual. A person who has been anemic for a very long time, with hemoglobin levels between 9 and 11 g/dL, usually has few or no symptoms other than slight tachycardia on exertion and fatigue.

Patients

who customarily are very active or who have significant demands on their lives

(eg, a single, working mother of small chil-dren) are more likely to have

symptoms, and those symptoms are more likely to be pronounced than in a more

sedentary person. A patient with hypothyroidism with decreased oxygen needs may

be completely asymptomatic, without tachycardia or increased cardiac output, at

a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL. Similarly, patients with coexistent cardiac,

vascular, or pulmonary disease may develop more pronounced symptoms of anemia

(eg, dyspnea, chest pain, muscle pain or cramping) at a higher hemoglobin level

than those without these concurrent health problems.

Finally,

some anemic disorders are complicated by various other abnormalities that do

not result from the anemia but are in-herently associated with these particular

diseases. These abnor-malities may give rise to symptoms that completely

overshadow those of the anemia, as in the painful crises of sickle cell anemia.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

A variety

of hematologic studies are performed to determine the type and cause of the

anemia. In an initial evaluation, the hemo-globin, hematocrit, reticulocyte

count, and RBC indices, particu-larly the mean corpuscular volume (MCV), are

particularly useful. Iron studies (serum iron level, total iron-binding

capacity [TIBC], percent saturation, and ferritin), as well as serum vitamin B12 and folate levels, are

also frequently obtained. Other tests include hap-toglobin and erythropoietin

levels. The remaining CBC values are useful in determining whether the anemia

is an isolated problem or part of another hematologic condition, such as

leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Bone marrow aspiration may be

performed. In addition, other diagnostic studies may be per-formed to determine

the presence of underlying chronic illness, such as malignancy, and the source

of any blood loss, such as polyps or ulcers within the gastrointestinal tract.

Complications

General

complications of severe anemia include heart failure, paresthesias, and

confusion. At any given level of anemia, patients with underlying heart disease

are far more likely to have angina or symptoms of heart failure than those

without heart disease. Com-plications associated with specific types of anemia

are included in the description of each type.

Medical Management

Management

of anemia is directed toward correcting or control-ling the cause of the

anemia; if the anemia is severe, the RBCs that are lost or destroyed may be

replaced with a transfusion of packed RBCs (PRBCs). The management of the

various types of anemia is covered in the discussions that follow.

Related Topics