Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hematologic Disorders

Acquired Thrombophilia - Coagulation Disorders

ACQUIRED

THROMBOPHILIA

Antibodies

to phospholipids are common, acquired causes for thrombophilia (hypercoagulable

states). The most common anti-bodies present against phospholipids are either

lupus or anti-cardiolipin antibodies. Both of these antibodies can be

transient, resulting from infection or certain medications. Most thrombotic

events are venous, but arterial thrombosis can occur in up to one third of the

cases. Patients who persistently test positive for either antibody and who have

had a thrombotic event are at significant risk for recurrent thrombosis

(greater than 50%). Recurrent throm-boses tend to be of the same type—that is,

venous thrombosis after an initial venous thrombosis, arterial thrombosis after

an initial arterial thrombosis.

Another

common acquired cause for thrombophilia is cancer. Specific types of stomach,

pancreatic, lung, and ovarian cancers are most commonly associated with

thrombophilia. The type of thrombosis that results is unusual. Rather than deep

vein throm-bosis or pulmonary embolism, the thrombosis occurs in unusual sites,

such as the portal, hepatic, or renal vein or the inferior vena cava. Migratory

superficial thrombophlebitis or nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis can also

occur. In these patients, anti-coagulation can be difficult to manage in that

the thrombosis can progress despite standard amounts of anticoagulation.

Medical Management

The

primary method of treating thrombotic disorders is antico-agulation. However,

in thrombophilic conditions, when to treat (prophylaxis or not) and how long to

treat (lifelong or not) can be controversial. Anticoagulation therapy is not

without risks; the most significant risk is bleeding. The most common

anticoagulant medications are identified in the following section.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Along

with administering anticoagulant therapy, concerns in-clude minimizing any risk

factors that predispose a patient to thrombosis. When risk factors (eg,

immobility after surgery, pregnancy) cannot be avoided, prophylactic

anticoagulation may be necessary.

Unfractionated Heparin Therapy.

Heparin is a

naturally occurringanticoagulant that enhances AT III and inhibits platelet

function. To prevent thrombosis, heparin is typically given as a subcuta-neous

injection, two or three times daily. To treat thrombosis, heparin is usually

administered intravenously. The therapeutic effect of heparin is monitored by

serial measurements of the acti-vated partial prothrombin time; the dose is

adjusted to maintain the range at 1.5 to 2.5 times the laboratory control. Oral

forms are being evaluated, but their absorption remains variable (Money &

York, 2001).

A

significant potential complication of heparin-based ther-apy is heparin-induced

thrombocytopenia (HIT). Antibodies are formed within the body against the

heparin complex. The actual incidence of HIT is unknown, but it is thought to

occur in as many as 5% patients receiving heparin (Kelton, 1999). Whereas most

patients remain asymptomatic, a significant pro-portion of those individuals

with serologic HIT develop actual thrombocytopenia. A decline in platelet count

typically devel-ops after 5 to 8 days of heparin therapy, and the platelets can

drop significantly, although in most instances the level stays higher than

50,000/mm3. These patients are at

increased risk for thrombosis, either venous or arterial, and the thrombosis

can range from DVT to myocardial infarction, CVA (brain at-tack, stroke), and

ischemic damage to an extremity necessitating amputation. The risk for

development of HIT appears to be increased when heparin is used at higher

concentrations (ie, ther-apeutic versus prophylactic dosage) and with

preexisting comor-bidity, such as underlying cardiac disease.

Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin Therapy.

Low

molecular-weightheparin (LMWH; eg, Dalteparin, Enoxaparin) is a special form of

heparin that has a more selective effect on coagulation. Based on its

biochemical properties, LMWH has a longer half-life and a less variable

anticoagulant response than does standard heparin. These differences permit

LMWH to be safely administered only once or twice daily, without the need for

laboratory monitoring for dose adjustments. The incidence of HIT is much lower

when LMWH is used. In certain conditions, the use of LMWH has allowed

anti-coagulation therapy to be moved entirely to the outpatient setting. Many

cases of uncomplicated DVT are being managed outside the hospital setting. LMWH

is also being increasingly used as “bridge therapy” when patients receiving

anticoagulation therapy (war-farin) require an invasive procedure (eg, biopsy,

surgery). In this sit-uation, warfarin is stopped and LMWH is used in its place

until the procedure is completed. After the procedure, warfarin therapy is

resumed. LMWH is discontinued after a therapeutic level of war-farin is

achieved.

Warfarin (Coumadin) Therapy.

Coumarin

anticoagulants (war-farin; eg, Coumadin) are antagonists of vitamin K and therefore

interfere with the synthesis of vitamin K–dependent clotting factors. Coumarin

anticoagulants bind to albumin, are metabo-lized in the liver, and have an

extremely long half-life. Typically, a patient is initially treated with both

heparin (either the unfrac-tionated form or LMWH) and warfarin. When the

international normalized ratio (INR) reaches the desired therapeutic range, the

heparin is stopped. The dosage required to maintain the therapeutic range (typically

using an INR of 2.0 to 3.0) varies widely among patients and even within the

same patient. Frequent mon-itoring of the INR is extremely important so that

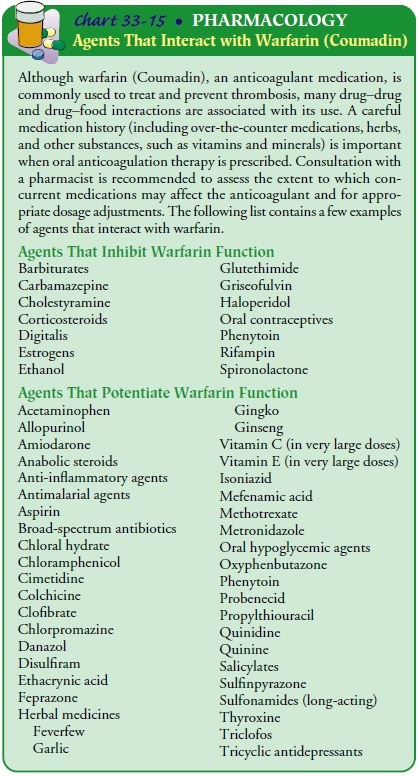

the dosage of warfarin can be adjusted as needed. Warfarin is affected by many

medications; consultation with a pharmacist is important to as-sess the extent

to which concurrently administered medications, herbs, and nutritional

supplements may interact with warfarin. It is also affected by many foods, so

patients need dietary instruc-tion and may benefit from consultation with a

dietitian when re-ceiving warfarin therapy. See Chart 33-15 for a listing of

agents that interact with warfarin.

Nursing Management

Patients with thrombotic disorders should avoid activities that promote circulatory stasis (eg, immobility, crossing the legs). Ex-ercise, especially ambulation, should be performed frequently throughout the day, particularly during long trips by car or plane.

Medications

that alter platelet aggregation, such as low-strength aspirin, may be prescribed.

Some patients require life-long ther-apy with anticoagulants such as warfarin

(eg, Coumadin).

Patients

with thrombotic disorders, particularly those with thrombophilia, should be

assessed for concurrent risk factors for thrombosis and should avoid concomitant

risk factors if possible. For example, use of tobacco and nicotine products

exacerbates the problem and should be avoided.

Just

as for other conditions, patients with thrombotic disor-ders, particularly

thrombophilia, should know the name of their specific condition and understand

its significance. In many in-stances, younger patients with thrombophilia may

not require prophylactic anticoagulation; however, with concomitant risk

fac-tors (eg, pregnancy), increasing age, or subsequent thrombotic events,

prophylactic or lifelong anticoagulation therapy may be re-quired. Being able

to provide the health care provider with an ac-curate health history can be

extremely useful and can help guide the selection of appropriate therapeutic

interventions. Patients with hereditary disorders should be encouraged to have

their sib-lings and children tested for the disorder.

When

patients with thrombotic disorders are hospitalized, fre-quent assessments

should be performed for signs and symptoms of beginning thrombus formation,

particularly in the legs (DVT) and lungs (pulmonary embolism). Ambulation or

range-of-motion ex-ercises as well as the use of elastic compression stockings

should be initiated promptly to decrease stasis. Prophylactic anticoagulants

are commonly prescribed.

Related Topics