Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hematologic Disorders

Nursing Process: The Patient With Acute Leukemia

NURSING

PROCESS: THE PATIENT WITH ACUTE LEUKEMIA

Assessment

Although

the clinical picture varies with the type of leukemia in-volved as well as the

treatment implemented, the health history may reveal a range of subtle symptoms

reported by the patient be-fore the problem is manifested by findings on

physical examina-tion. Weakness and fatigue are common manifestations, not only

of the leukemia but also of the resulting complications of anemia and

infection. If the patient is hospitalized, the assessments should be performed

daily, or more frequently as warranted. Because the physical findings may be

subtle initially, a thorough, systematic as-sessment incorporating all body

systems is essential. For example, a dry cough, mild dyspnea, and diminished

breath sounds may in-dicate a pulmonary infection. However, the infection may

not be seen initially on the chest x-ray. The lack of neutrophils delays the

inflammatory response against the pulmonary infection, and it is the

inflammatory response that causes the x-ray changes. The platelet count can

become dangerously low, leaving the patient at risk for significant bleeding.

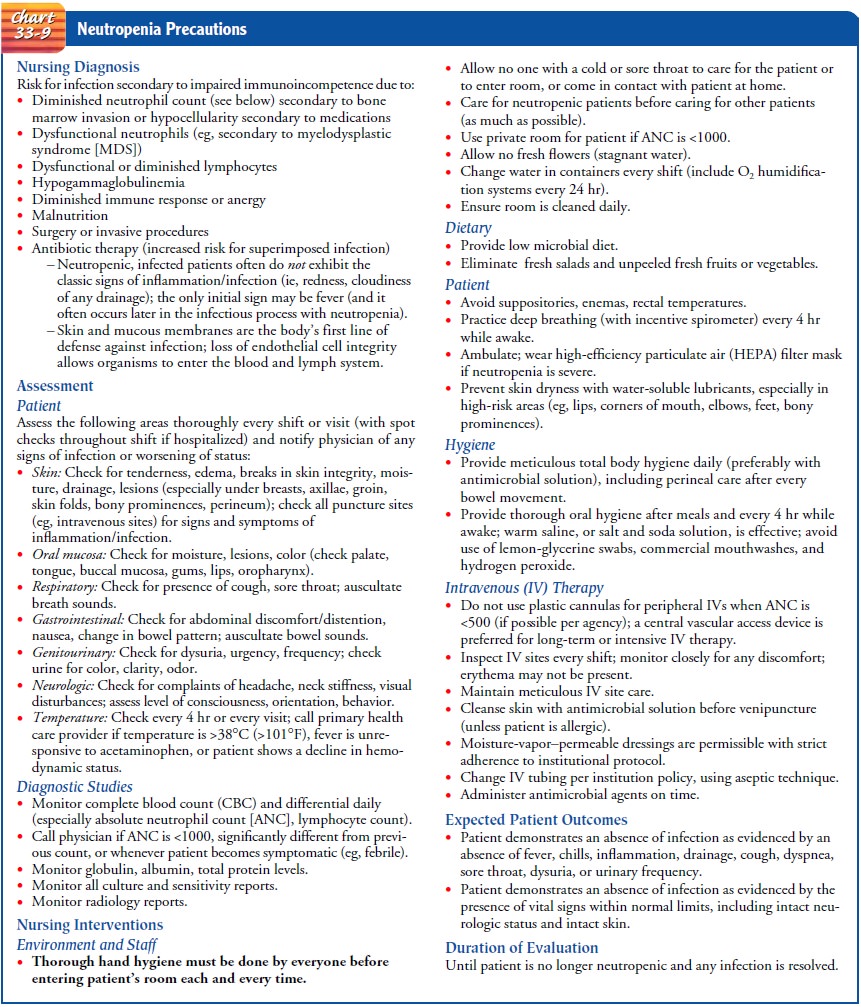

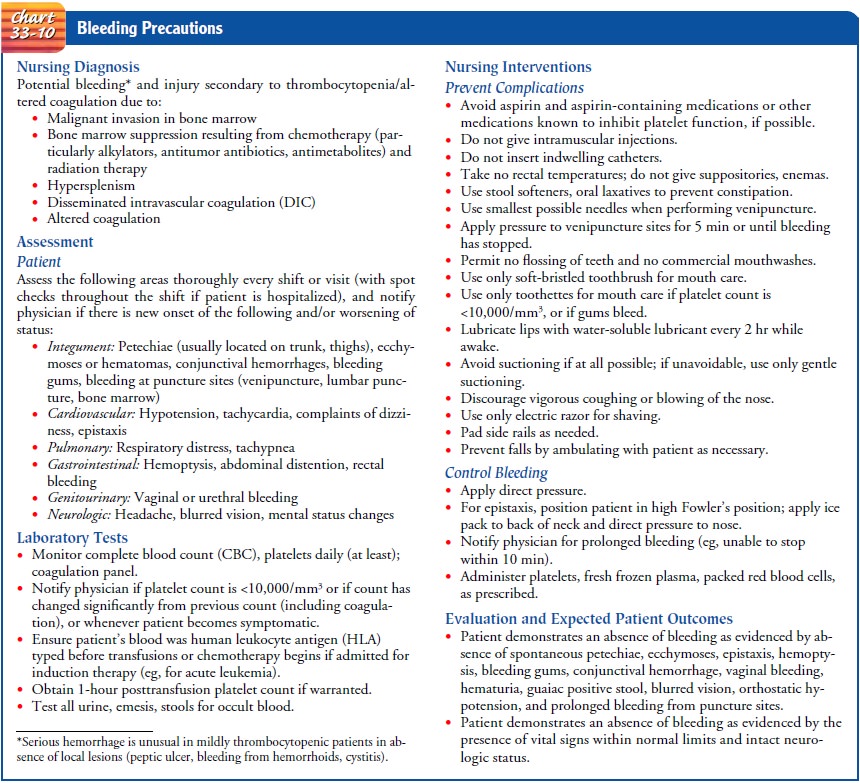

The specific body system assessments are delineated in the neutropenic

precautions and bleeding pre-cautions, found in Charts 33-9 and 33-10,

respectively. When se-rial assessments are performed, current findings are

compared with previous findings to evaluate improvement or worsening.

The nurse also must closely monitor the results of laboratory studies. Flow sheets and spreadsheets are particularly useful in tracking the WBC count, ANC, hematocrit, platelet, and creatinine levels, hepatic function tests, and electrolyte levels. Culture results need to be reported immediately so that appropriate antimicrobial therapy can begin or be modified.

Diagnosis

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Based

on the assessment data, major nursing diagnoses for the pa-tient with acute

leukemic may include:

•

Risk for infection and bleeding

•

Risk for impaired skin integrity related to toxic

effects of chemotherapy, alteration in nutrition, and impaired mobility

•

Impaired gas exchange

•

Impaired mucous membranes due to changes in

epithelial lining of the gastrointestinal tract from chemotherapy or prolonged

use of antimicrobial medications

•

Imbalanced nutrition, less than body requirements,

related to hypermetabolic state, anorexia, mucositis, pain, and nausea

•

Acute pain and discomfort related to mucositis, WBC

in-filtration of systemic tissues, fever, and infection

•

Hyperthermia related to tumor lysis and infection

•

Fatigue and activity intolerance related to anemia

and infection

•

Impaired physical mobility due to anemia and protective

isolation

•

Risk for excess fluid volume related to renal

dysfunction, hypoproteinemia, need for multiple intravenous medica-tions and

blood products

•

Diarrhea due to altered gastrointestinal flora,

mucosal denudation

•

Risk for deficient fluid volume related to

potential for diar-rhea, bleeding, infection, and increased metabolic rate

•

Self-care deficit due to fatigue, malaise, and

protective isolation

•

Anxiety due to knowledge deficit and uncertain

future

•

Disturbed body image related to change in

appearance, function, and roles

•

Grieving related to anticipatory loss and altered

role func-tioning

•

Potential for spiritual distress

•

Deficient knowledge about disease process,

treatment, com-plication management, and self-care measures

COLLABORATIVE PROBLEMS/POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Based

on the assessment data, potential complications that may develop include:

•

Infection

•

Bleeding

•

Renal dysfunction

•

Tumor lysis syndrome

•

Nutritional depletion

•

Mucositis

Planning and Goals

The

major goals for the patient may include absence of com-plications and pain,

attainment and maintenance of adequate nutrition, activity tolerance, ability

for self-care and to cope with the diagnosis and prognosis, positive body

image, and an understanding of the disease process and its treatment.

Nursing Interventions

PREVENTING OR MANAGING INFECTION AND BLEEDING

The

nursing interventions related to diminishing the risk for in-fection and for

bleeding are delineated in Charts 33-9 and 33-10.

MANAGING MUCOSITIS

Although

emphasis is placed on the oral mucosa, it is important to realize that the

entire gastrointestinal mucosa can be altered, not only by the effects of

chemotherapy but also from prolonged ad-ministration of antibiotics. Assessment

of the oral mucosa must be thorough; therefore, dentures must be removed. Areas

to assess in-clude the palate, buccal mucosa, tongue, gums, lips, oropharynx,

and the area under the tongue. In addition to identifying and describing

lesions, the color and moisture of the mucosa should be noted.

Oral

hygiene is very important to diminish the bacteria within the mouth, maintain

moisture, and provide comfort. Soft-bristled toothbrushes should be used until

the neutrophil and platelet counts become very low; at that time, sponge-tipped

applicators should be substituted. Lemon-glycerin swabs and commercial

mouthwashes should never be used because the glycerin and alco-hol within them

are extremely drying to the tissues. Simple rinses with saline (or saline and

baking soda) solutions are inexpensive but effective in cleaning and moistening

the oral mucosa. Because the risk of yeast or fungal infection in the mouth is

great, other medications are often prescribed, such as chlorhexidine rinses

(eg, Peridex) or clotrimazole troches (eg, Mycelex). The nurse re-minds the

patient about the importance of these medications to enhance adherence to the

therapeutic regimen. Chlorhexidine rinses may discolor the teeth.

To

diminish perineal–rectal complications, it is important to cleanse the

perineal–rectal area thoroughly after each bowel movement. Women are instructed

to cleanse the perineum from front to back. Sitz baths are a comfortable method

of cleansing; the perineal–anal region and buttocks must be carefully dried

after-ward to minimize the chance of excoriation. Stool softeners should be

used to increase the moisture of bowel movements; however, the stool texture

must be monitored so that the softeners can be decreased or stopped if the

stool becomes too loose.

IMPROVING NUTRITIONAL INTAKE

The

disease process can increase, and sepsis further increases, the patient’s

metabolic rate and nutritional requirements. Nutri-tional intake is often

reduced because of pain and discomfort as-sociated with stomatitis. Mouth care

before and after meals and administration of analgesics before eating can help

increase in-take. If oral anesthetics are used, the patient must be warned to

chew with extreme care to avoid inadvertently biting the tongue or buccal

mucosa.

Nausea

should not be a major contributing factor, because re-cent advances in

antiemetic therapy are highly effective. However, nausea can result from

antimicrobial therapy, so some antiemetic therapy may still be required after

the chemotherapy has been completed.

Small,

frequent feedings of foods that are soft in texture and moderate in temperature

may be better tolerated. Low-microbial diets are typically prescribed (avoiding

uncooked fruits or vegetables and those without a peelable skin). Nutritional

sup-plements are frequently used. Daily body weights (as well as in take and

output measurements) are useful in monitoring fluid status.

Calorie

counts are useful, as are more formal nutritional assess-ments. Parenteral

nutrition is often required to maintain adequate nutrition.

EASING PAIN AND DISCOMFORT

Recurrent

fevers are common in acute leukemia; at times, they are accompanied by shaking

chills, which can be severe (rigors). Myalgias and arthralgias can result.

Acetaminophen is typically given to decrease fever, but it does so by

increasing diaphoresis. Sponging with cool water may be useful, but cold water

or ice packs should be avoided because the heat cannot dissipate from

constricted blood vessels. Bedclothes need frequent changing as well. Gentle

back and shoulder massage may provide comfort.

Stomatitis

can also cause significant discomfort. In addition to oral hygiene practices,

patient-controlled analgesia can be effective in controlling the pain.

Because

patients with acute leukemia require hospitalization for extensive nursing care

(either during induction or consolida-tion therapy or during resultant

complications), sleep deprivation frequently results. Nurses need to implement

creative strategies that permit uninterrupted sleep for at least a few hours

while still administering necessary medications on time.

With

the exception of severe mucositis, less pain is associated with acute leukemia

than with many other forms of cancer. How-ever, the amount of psychologic

suffering that the patient must en-dure can be immense. Patients greatly benefit

from active listening.

DECREASING FATIGUE AND DECONDITIONING

Fatigue

is a common and oppressive problem. Nursing interven-tions should focus on

assisting the patient to establish a balance be-tween activity and rest.

Patients with acute leukemia need to maintain some physical activity and

exercise to prevent the decon-ditioning that results from inactivity. Use of a

high-efficiency par-ticulate air (HEPA) filter mask can permit the patient to

ambulate outside the room despite severe neutropenia. Although many pa-tients

lack the motivation to use them, stationary bicycles within the room can also

be used. At a minimum, patients should be en-couraged to sit up in a chair

while awake rather than staying in bed; even this simple activity can improve the

patient’s tidal volume and enhance circulation. Physical therapy can also be

beneficial.

MAINTAINING FLUID AND ELECTROLYTE BALANCE

Febrile

episodes, bleeding, and inadequate or overly aggressive fluid replacement can

alter the patient’s fluid status. Similarly, persistent diarrhea, vomiting, and

long-term use of certain anti-microbial agents can cause significant deficits

in electrolytes. In-take and output need to be measured accurately, and daily

weights should also be monitored. The patient should be assessed for signs of

dehydration as well as fluid overload, with particular at-tention to pulmonary

status and the development of dependent edema. Laboratory test results,

particularly electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and hematocrit,

should be monitored and compared with previous results. Replacement of

electrolytes, par-ticularly potassium and magnesium, is commonly required.

Pa-tients receiving amphotericin or certain antibiotics are at increased risk

for electrolyte depletion.

IMPROVING SELF-CARE

Because

hygiene measures are so important in this patient popu-lation, they must be

performed by the nurse when the patient can-not do so. However, the patient

should be encouraged to do as much as possible, to preserve mobility and

function as well as self-esteem. Patients may have negative feelings, even

disgust that they can no longer care for themselves. Empathetic listening is

helpful, as is realistic reassurance that these deficits are temporary. As the

patient recovers, it is important to assist him or her to resume more

self-care. Patients are usually discharged from the hospital with a central

vascular access device (eg, Hickman catheter, PICC), and most patients can care

for the catheter with adequate instruction and practice under observation.

MANAGING ANXIETY AND GRIEF

Being

diagnosed with acute leukemia can be extremely frighten-ing. In many instances,

the need to begin treatment is emergent, and patients have little time to

process the fact that they have the illness before making decisions about

therapy. Providing emo-tional support and discussing the uncertain future are

crucial. The nurse also needs to assess how much information patients want to

have regarding the illness, its treatment, and potential complications. This

desire should be reassessed at intervals, be-cause needs and interest in

information change throughout the course of the disease and treatment.

Priorities must be identified so that procedures, assessments, and self-care

expectations are adequately explained even to those who do not wish extensive

information.

Many

patients become depressed and begin to grieve for the losses they feel, such as

normal family functioning, professional roles and responsibilities, and social

roles, as well as physical func-tioning. Nurses can assist patients to identify

the source of the grief and encourage them to allow time to adjust to the major

life changes produced by the illness. Role restructuring, in both fam-ily and

professional life, may be required. Again, when possible, permitting patients

to identify options and to take time making significant decisions regarding

such restructuring is helpful.

Discharge

from the hospital can also provoke anxiety. Although most patients are

extremely eager to go home, they may lack con-fidence in their ability to

manage potential complications and to resume their normal activity. Close

communication between nurses across care settings can reassure patients that

they will not be abandoned.

ENCOURAGING SPIRITUAL WELL-BEING

Because

acute leukemia is a serious, potentially life-threatening illness, the nurse

may offer support to enhance the patient’s spir-itual well-being. The patient’s

spiritual and religious practices should be assessed and pastoral services

offered. Throughout the patient’s illness, it is important that the nurse

assist the patient to maintain hope. However, that hope should be realistic and

will certainly change over the course of the illness. For example, the patient

may initially hope to be cured, but with repeated relapses and a change to

terminal care the same patient may hope for a quiet, dignified death.

MONITORING AND MANAGING POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Nursing

interventions for potential complications were described previously.

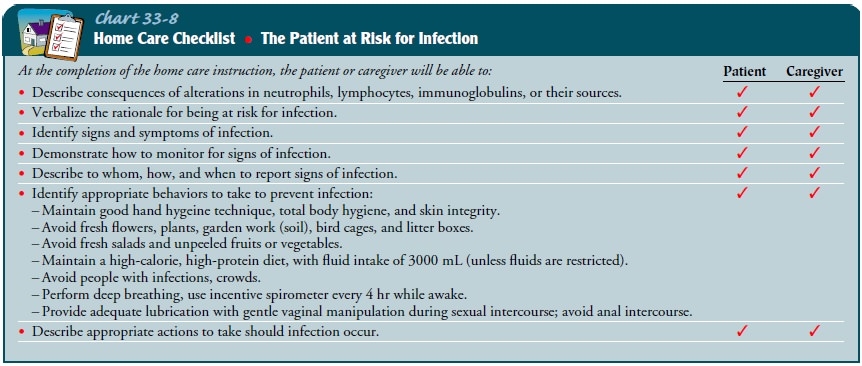

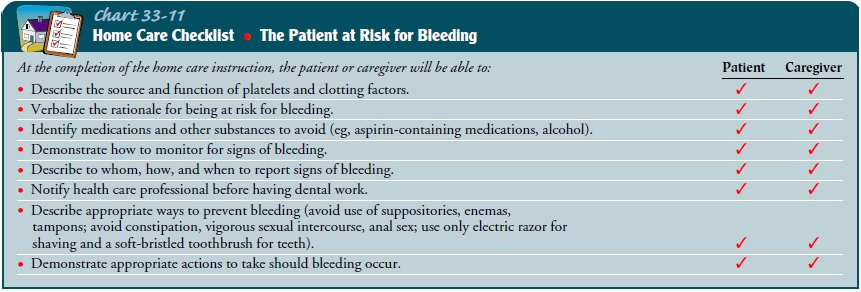

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care

Most

patients cope better when they have an understanding of what is happening to

them. Based on their education, literacy level, and interest, teaching of

patient and family should focus on the disease (including some pathophysiology),

its treatment, and certainly the significant risk for infection and bleeding

(Charts 33-8 and 33-11) that results.

Management

of a vascular access device can be taught to most patients or family members.

Follow-up and care for the devices may also need to be provided by nurses in an

outpatient facility or by a home care agency or a health care providerv.

Continuing Care.

Shortened

hospital stays and outpatient carehave significantly altered care for patients

with acute leukemia. In many instances, when the patient is clinically stable

but still re-quires parenteral antibiotics or blood products, these procedures

can be performed in an outpatient setting. Nurses in these vari-ous settings

must communicate regularly. Patients need to learn which parameters are

important for them to monitor, and how to monitor them. Specific instructions

need to be given as to when the patient should seek care from the physician or

a health care provider.

Patients

and their families need to have a clear understand-ing of the disease and the

prognosis. The nurse acts as an advo-cate to ensure that this information is

provided. When patients no longer respond to therapy, it is important to

respect their choices about treatment, including measures to prolong life and

other end-of-life measures. Advance directives and living wills provide

patients with some measure of control during terminal illness.

Many

patients in this stage still choose to be cared for at home, and families often

need support when considering this option. Coordination of home care services

and instruction can help to alleviate anxiety about managing the patient’s care

in the home. As the patient becomes weaker, the caregivers must assume more of

the patient’s care. In addition, caregivers often need to be en-couraged to

take care of themselves, allowing time for rest and ac-cepting emotional

support. Hospice staff can assist in providing respite for family members as

well as care for the patient. Patients and families also need assistance to

cope with changes in their roles and responsibilities. Anticipatory grieving is

an essential task during this time.

In

patients with acute leukemia, death typically occurs from infection or

bleeding. Family members need to have informa-tion about these complications

and the measures to take should either occur. Many family members cannot cope

with the care required when a patient begins to bleed actively. It is important

to delineate alternatives to keeping the patient at home. Should another option

be sought, family members who may feel guilty that they could not keep the

patient at home will require sup-port from the nurse.

Evaluation

EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES

Expected

patient outcomes may include:

1) Shows no evidence of

infection

2) Experiences no bleeding

3) Has intact oral mucous

membranes

a) Participates in oral

hygiene regimen

b) Reports no discomfort in

mouth

4) Attains optimal level of

nutrition

a) Maintains weight with

increased food and fluid intake

b) Maintains adequate

protein stores (albumin)

5) Reports satisfaction

with pain and discomfort levels

6) Has less fatigue and

increased activity

7) Maintains fluid and

electrolyte balance

8) Participates in

self-care

9) Copes with anxiety and

grief

a) Discusses concerns and

fears

b) Uses stress management

strategies appropriately

c) Participates in

decisions regarding end-of-life care

10) Absence of complications

Related Topics