Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hematologic Disorders

Iron Deficiency Anemia

Hypoproliferative Anemias

IRON

DEFICIENCY ANEMIA

Iron

deficiency anemia typically results when the intake of dietary iron is

inadequate for hemoglobin synthesis. The body can store about one fourth to one

third of its iron, and it is not until those stores are depleted that iron

deficiency anemia actually begins to develop. Iron deficiency anemia is the

most common type of ane-mia in all age groups, and it is the most common anemia

in the world. More than 500 million people are affected, more com-monly in

underdeveloped countries, where inadequate iron stores can result from

inadequate intake of iron (seen with vegetarian diets) or from blood loss (eg,

from intestinal hookworm). Iron deficiency is also common in the United States.

In children, ado-lescents, and pregnant women, the cause is typically

inadequate iron in the diet to keep up with increased growth. However, for most

adults with iron deficiency anemia, the cause is blood loss. In fact, in

adults, the cause of iron deficiency anemia should be considered to be bleeding

until proven otherwise.

The

most common cause of iron deficiency in men and post-menopausal women is

bleeding (from ulcers, gastritis, inflamma-tory bowel disease, or

gastrointestinal tumors). The most common cause of iron deficiency anemia in

premenopausal women is men-orrhagia (excessive menstrual bleeding) and

pregnancy with in-adequate iron supplementation. Patients with chronic

alcoholism often have chronic blood loss from the gastrointestinal tract, which

causes iron loss and eventual anemia. Other causes include iron malabsorption,

as is seen after gastrectomy or with celiac disease.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients

with iron deficiency primarily have the symptoms of ane-mia. If the deficiency

is severe or prolonged, they may also have a smooth, sore tongue, brittle and

ridged nails, and angular cheilosis (an ulceration of the corner of the mouth).

These signs subside after iron-replacement therapy. The health history may be

significant for multiple pregnancies, gastrointestinal bleeding, and pica (a

craving for unusual substances, such as ice, clay, or laundry starch).

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The

most definitive method of establishing the diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia

is bone marrow aspiration. The aspirate is stained to detect iron, which is at

a low level or even absent. However, few patients with suspected iron

deficiency anemia undergo bone marrow aspiration. In many patients, the

diagnosis can be established with other tests, particularly in patients with a

history of conditions that predispose them to this type of anemia.

There

is a strong correlation between laboratory values mea-suring iron stores and

levels of hemoglobin. After the iron stores are depleted (as reflected by low

serum ferritin levels), the hemo-globin level falls. The diminished iron stores

cause small RBCs. Therefore, as the anemia progresses, the MCV, which measures

the size of the RBC, also decreases. Hematocrit and RBC levels are also low in

relation to the hemoglobin level. Other laboratory tests that measure iron

stores are useful but are not as consistent indicators as a low ferritin level,

which reflects low iron stores. Typically, patients with iron deficiency anemia

have a low serum iron level and an elevated TIBC, which measures the transport

protein supplying the marrow with iron as needed (also referred to as

transferrin). However, other disease states, such as infection and inflammatory

conditions, can also cause a low serum iron level and TIBC with an elevated

ferritin level. Therefore, the most reliable laboratory findings in evaluating

iron deficiency anemia are the ferritin and hemoglobin values.

Medical Management

Except

in the case of pregnancy, the cause of iron deficiency should be investigated.

Anemia may be a sign of a curable gastro-intestinal cancer or of uterine

fibroid tumors. Stool specimens should be tested for occult blood. People 50

years of age or older should have a colonoscopy, endoscopy, or other

examination of the gastrointestinal tract to detect ulcerations, gastritis,

polyps, or cancer. Several oral iron preparations—ferrous sulfate, ferrous

gluconate, and ferrous fumarate—are available for treating iron deficiency

anemia. In some cases, oral iron is poorly absorbed or poorly tolerated, or

iron supplementation is needed in large amounts. In these situations, intravenous

or intramuscular admin-istration of iron dextran may be needed. Before

parenteral administration of a full dose, a small test dose should be

adminis-tered to avoid the risk of anaphylaxis with either intravenous or

in-tramuscular injections. Emergency medications (eg, epinephrine) should be

close at hand.If no signs of allergic reaction have occured after 30 minutes,

the remaining dose of iron may be administered. Several doses are required to

replenish the patient’s iron stores.

Nursing Management

Preventive

education is important, because iron deficiency anemia is common in

menstruating and pregnant women. Food sources high in iron include organ meats

(beef or calf’s liver, chicken liver), other meats, beans (black, pinto, and

garbanzo), leafy green veg-etables, raisins, and molasses. Taking iron-rich

foods with a source of vitamin C enhances the absorption of iron.

The

nurse helps the patient select a healthy diet. Nutritional counseling can be

provided for those whose usual diet is inade-quate. Patients with a history of

eating fad diets or strict vegetar-ian diets are counseled that such diets

often contain inadequate amounts of absorbable iron. The nurse encourages

patients to con-tinue iron therapy as long as it is prescribed, although they

may no longer feel fatigued.

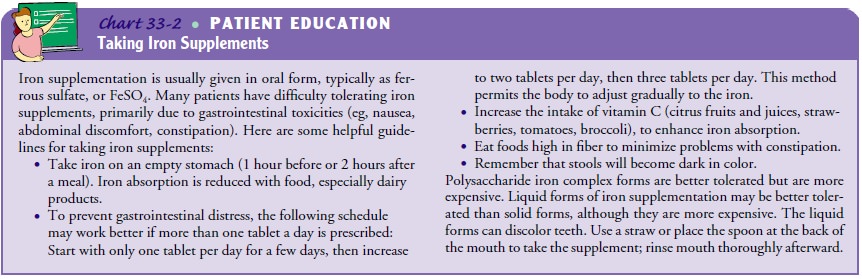

Because

iron is best absorbed on an empty stomach, patients should be advised to take

the supplement an hour before meals. Most patients can use the less expensive,

more standard forms of ferrous sulfate. Tablets with enteric coating may be

poorly

absorbed

and should be avoided. Other patients have difficulty taking iron supplements

because of gastrointestinal side effects (primarily constipation, but also

cramping, nausea, and vomiting). Some iron formulations are designed to limit

gastrointestinal side effects by the addition of a stool softener or use of

sustained-release formulations to limit nausea or gastritis. Specific patient

teaching aids, such as the accompanying patient education guide (Chart 33-2),

can assist patients with the use of iron supplements.

If

taking iron on an empty stomach causes gastric distress, the patient may need

to take the iron supplement with meals. How-ever, doing so diminishes iron

absorption by as much as 50%, thus prolonging the time required to replenish

iron stores. Antacids or dairy products should not be taken with iron, because

they greatly diminish the absorption of iron. Polysaccharide iron complex forms

that have less gastrointestinal toxicity are also available, but they are more

expensive.

Liquid

forms of iron that cause less gastrointestinal distress are available. However,

they can stain the teeth; patients should be in-structed to take this

medication through a straw, to rinse the mouth with water, and to practice good

oral hygiene after taking this med-ication. Finally, patients should be

informed that iron salts may color the stool dark green or black. However, iron

replacement therapy does not cause a false-positive result on stool analyses for

occult blood.

Intramuscular

supplementation is used infrequently. The vol-ume of iron required may be

excessive. The intramuscular injec-tion causes some local pain and can stain

the skin. These side effects are minimized by using the Z-track technique for

administering iron dextran deep into the gluteus maximus muscle (buttock).

Avoid vigorously rubbing the injection site after the injection. Be-cause of

the problems with intramuscular administration, the in-travenous route is

preferred for administration of iron dextran.

Related Topics