Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hematologic Disorders

HodgkinŌĆÖs Disease

The Lymphomas

The

lymphomas are neoplasms of cells of lymphoid origin. These tumors usually start

in lymph nodes but can involve lymphoid tissue in the spleen, the

gastrointestinal tract (eg, the wall of the stomach), the liver, or the bone

marrow. They are often classified according to the degree of cell

differentiation and the origin of the predominant malignant cell. Lymphomas can

be broadly clas-sified into two categories: HodgkinŌĆÖs disease and non-HodgkinŌĆÖs

lymphoma (NHL).

HODGKINŌĆÖS

DISEASE

HodgkinŌĆÖs

disease is a relatively rare malignancy that has an im-pressive cure rate. It

is somewhat more common in men than women and has two peaks of incidence: one

in the early 20s and the other after 50 years of age. Unlike other lymphomas,

HodgkinŌĆÖs disease is unicentric in origin in that it initiates in a sin-gle

node. The disease spreads by contiguous extension along the lymphatic system.

The cause of HodgkinŌĆÖs disease is unknown, but a viral etiology is suspected.

In fact, fragments of the Epstein-Barr virus have been found in 40% to 50% of

patients; this occurs more commonly in the younger patient population (Weiss,

2000). There is a familial pattern associated with HodgkinŌĆÖs disease:

first-degree relatives have a higher-than-normal frequency of the dis-ease.

There is no increased incidence documented for non-blood relatives (eg,

spouses).

The

malignant cell of HodgkinŌĆÖs disease is the Reed-Sternberg cell, a gigantic

tumor cell that is morphologically unique and is thought to be of immature

lymphoid origin. It is the pathologic hallmark and essential diagnostic

criterion for HodgkinŌĆÖs disease. However, the tumor is very heterogeneous and

may actually con-tain few Reed-Sternberg cells. Repeated biopsies may be

required to establish the diagnosis.

HodgkinŌĆÖs disease is customarily classified

into five subgroups based on pathologic analyses that reflect the natural

history of the malignancy and suggest the prognosis. For example, when

lym-phocytes predominate, with few Reed-Sternberg cells and minimal involvement

of the lymph nodes, the prognosis is much more fa-vorable than when the

lymphocyte count is low and the lymph nodes are virtually replaced by tumor

cells of the most primitive type. The majority of patients with HodgkinŌĆÖs

disease have the types currently designated ŌĆ£nodular sclerosisŌĆØ or ŌĆ£mixed

cellularity.ŌĆØ The nodular sclerosis type tends to occur more often in young

women, at an earlier stage but with a worse prognosis than the mixed

cellu-larity subgroup, which occurs more commonly in men and causes more

constitutional symptoms but has a better prognosis.

Clinical Manifestations

HodgkinŌĆÖs

disease usually begins as a painless enlargement of one or more lymph nodes on

one side of the neck. The individual nodes are painless and firm but not hard.

The most common sites for lymphadenopathy are the cervical, supraclavicular,

and medi-astinal nodes; involvement of the iliac or inguinal nodes or spleen is

much less common. A mediastinal mass may be seen on chest x-ray; occasionally,

the mass is large enough to compress the trachea and cause dyspnea. Pruritus is

common; it can be extremely dis-tressing, and the cause is unknown. Approximately

20% of patients experience brief but severe pain after drinking alcohol

(Cavalli, 1998). The pain is usually at the site of the HodgkinŌĆÖs disease;

again, the cause is unknown.

All

organs are vulnerable to invasion by HodgkinŌĆÖs disease. The symptoms result

from compression of organs by the tumor, such as cough and pulmonary effusion

(from pulmonary infiltrates), jaundice (from hepatic involvement or bile duct

obstruction), ab-dominal pain (from splenomegaly or retroperitoneal

adenopathy), or bone pain (from skeletal involvement). Herpes zoster infections

are common. A cluster of constitutional symptoms has important prognostic

implications. Referred to as ŌĆ£B symptoms,ŌĆØ they include fever (without chills),

drenching sweats (particularly at night), and unintentional weight loss of more

than 10%. ŌĆ£B symptomsŌĆØ are found in 40% of patients and are more common in

advanced disease.

A mild

anemia is the most common hematologic finding. The WBC count may be elevated or

decreased. The platelet count is typically normal, unless the tumor has invaded

the bone marrow, suppressing hematopoiesis. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate(ESR) and the serum copper level are

used by some clinicians toassess disease activity. Patients with HodgkinŌĆÖs

disease have im-paired cellular immunity, as evidenced by an absent or

decreased reaction to skin sensitivity tests (eg, Candida, mumps).

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Because

many manifestations are similar to those occurring with infection, diagnostic

studies are performed to rule out an infectious origin for the disease. The

diagnosis is made by means of an exci-sional lymph node biopsy and the finding

of the Reed-Sternberg cell. Once the diagnosis is confirmed and the histologic

type is es-tablished, it is necessary to assess the extent of the disease, a

process referred to as staging.During the health history, the nurse should assess

for any ŌĆ£B symptoms.ŌĆØ Physical examination requires a careful, systematic

evaluation of the lymph node chains, as well as the size of the spleen and

liver. A chest x-ray and a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis are

crucial to identify the extent of lymphadenopathy within these regions.

Laboratory tests include CBC, platelet count, ESR, and liver and renal function

studies. A bone marrow biopsy is per-formed if there are signs of marrow

involvement, and some physi-cians routinely perform bilateral biopsies. Bone

scans may be performed to identify any involvement in these areas. A staging

la-parotomy and lymphangiography are no longer considered manda-tory, primarily

because of the accuracy of CT.

Medical Management

The

general intent in treating HodgkinŌĆÖs disease, regardless of stage, is cure.

Treatment is determined primarily by the stage of the disease, not the

histologic type; however, extensive research is ongoing to target treatment

regimens to histologic subtypes or prognostic features. Traditionally, early

HodgkinŌĆÖs disease was treated by a staging laparotomy followed by radiation

therapy. Re-cent data show improved results and decreased complications with a

short course (2 to 4 months) of chemotherapy followed by radi-ation therapy in

certain subsets of early-stage disease (IA and IIA); patients with early-stage

disease and good prognostic features may receive radiation therapy alone (Hoppe

et al., 2000). Combina-tion chemotherapy, for example with doxorubicin

(Adriamycin), bleomycin (Blenoxane), vinblastine (Velban), and dacarbazine

(DTIC), referred to as ABVD, is now the standard treatment for more advanced

disease (stages III and IV and all B stages).

Radiation

therapy is still very useful for patients with exten-sive adenopathy (often

termed bulky disease). In this group, residual disease often persists after the

chemotherapy treatment is finished; radiation therapy to the areas of remaining

adenopathy has been shown to improve survival.

Even

when HodgkinŌĆÖs disease does recur, the use of high doses of chemotherapeutic

agents, followed by autologous BMT or stem cell transplantation (PBSCT), can be

very effective in controlling the disease and extending survival time.

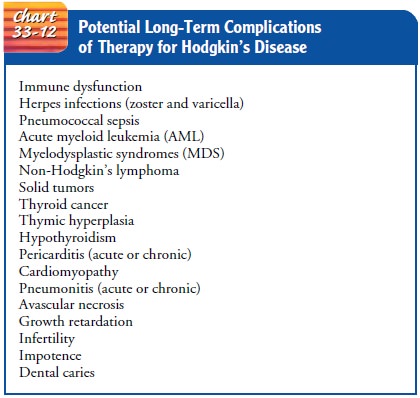

Long-Term Complications of Therapy

Much

is now known about the long-term effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy,

primarily from the large numbers of peo-ple who were cured of HodgkinŌĆÖs disease

by these treatments. The various complications of treatment are listed in Chart

33-12. Risk factors for other cancers should be assessed, and long-term

sur-veillance is crucial. The potential development of a second malig-nancy is

obviously of concern to patients, and this potential should be addressed with

the patient when treatment decisions are made. However, it is important to

consider that HodgkinŌĆÖs disease is cur-able. Revised treatment approaches are

aimed at diminishing the risk for complications without sacrificing the

potential for cure.

Related Topics