Chapter: Psychology: Sensation

The Stimulus: Light

The Stimulus:

Light

Many objects in our surroundings—the sun, candles, lamps, and so on—produce light that’s then reflected off most other objects. It’s usually reflected light—from this view, for example, or from a friend’s face—that launches the processes of vision.

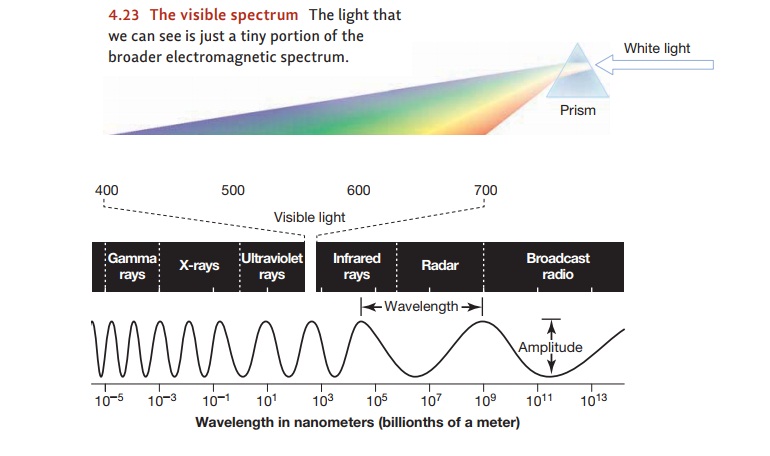

Whether it’s emitted or

reflected, the stimulus energy we call “light” can be under-stood as traveling

in waves. Like sound waves, these light waves can be described in terms of two

measurements. First, light waves can vary in amplitude, which is the major

determinant of perceived brightness. A light wave’s amplitude is measured as

the “height” of the waves, starting from the wave’s baseline. Second, light

waves vary in frequency—how many times per second the wave reaches its maximum

amplitude. As it turns out, these frequencies are extremely high because light

travels so swiftly. It’s more convenient, therefore, to describe light waves

using the inverse of frequency—wavelength, the distance between the crests of

two successive waves. Wavelengths are measured in nanometers (billionths of a

meter) and are the major determinant of perceived color.

The wavelengths our visual system

can sense are only a tiny part of the broader electromagnetic spectrum (Figure

4.23). Light with a wavelength longer than 750 nanometers is invisible to us,

although we do feel these longer infrared waves as heat. Ultraviolet light,

which has a wavelength shorter than 360 nanometers, is also invisible to us.

That leaves the narrow band of wavelengths between 750 and 360 nanometers— the

so-called visible spectrum. Within

this spectrum, we usually see wavelengths close to 400 nanometers as violet,

those close to 700 nanometers as red, and those in between as the rest of the

colors in the rainbow.

Be aware, though, that the

boundaries of the visible spectrum are not physical boundaries indicating some

kind of break in the electromagnetic spectrum. Instead, these boundaries simply

identify the part of the spectrum that human eyes can detect. Other species,

with different types of eyes, perceive different subsets of the broader

spectrum. Bees can perceive ultraviolet wavelengths that are invisible to us;

other mammals, including some types of monkeys, can tell apart wavelengths that

look identical to us.

Related Topics