Chapter: Psychology: Sensation

A Survey of the Senses: The Skin Senses

The Skin Senses

The Greek philosopher Aristotle

believed that all of the senses from the skin were encompassed in the broad

category of touch. Today we know that

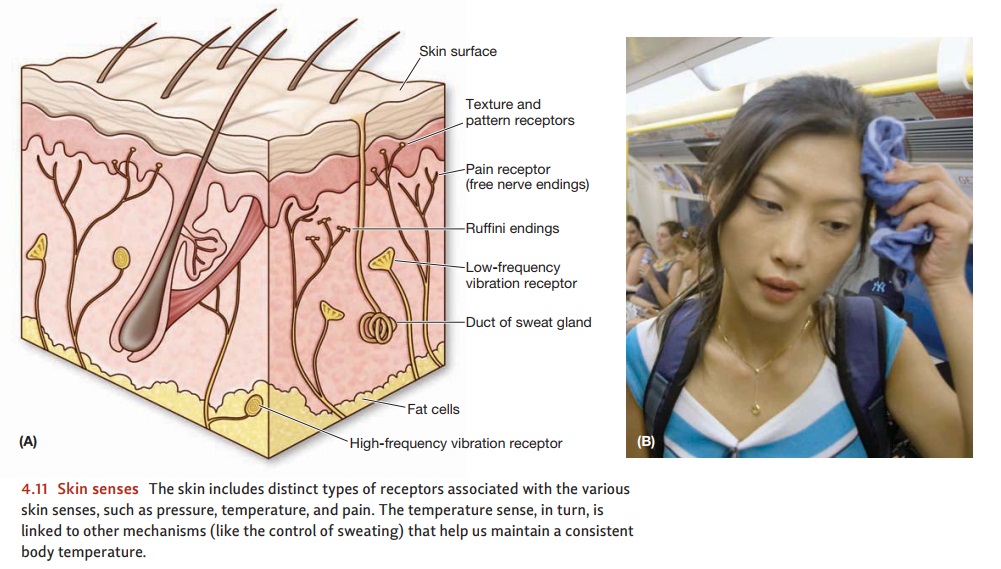

the so-called skinsenses include

several distinct subsystems, each giving rise to a distinct sensation—including

pressure, temperature, and pain (Figure 4.11). Not surprisingly, some parts of

the body have greater skin sensitivity than others—it’s especially high in the

hands and fingers, the lips and tongue, and the genital areas.

Among the various senses, the

skin senses may be the best example of specificity cod-ing (or “labeled

lines”), whereby distinct types of receptors are associated with different

sensations. Some of the receptors respond to sustained pressure or very

low-frequency vibration. A second type of receptors respond to faster

vibrations. Yet another type, called the Ruffini endings, respond to sustained

downward pressure or stretching of the skin; among other functions, these

latter receptors probably play a key role in helping us mon-itor and control

our finger positions.

Still other receptors are

responsible for our sensitivity to temperature—and even here, we encounter

specialization. One type of receptor fires whenever the temperature increases

in the area immediately surrounding the receptor; a different (and more

numerous) type of receptor does the opposite—firing in response to a drop in

skin temperature. It turns out that, in most cases, neither of these receptor

types is especially active. This is because many mechanisms inside the body

work to maintain a constant body temperature, and so neither receptor type is

triggered. But if you move close to the radiator or step into cold water, these

receptors immediately respond, informing you about these events.

Related Topics