Chapter: Psychology: Sensation

A Survey of the Senses: Sensory Adaptation

Sensory

Adaptation

One further consideration is also

relevant to all the sensory systems. Of course, our sensory responses are

influenced by the physical magnitude of the stimulus—and so the taste buds

respond more powerfully to a concentrated sugar solution than a weak one; the

eye responds more strongly to a bright light than a dim one. But our sensory

responses are also influenced by changes.

Thus, a sugar solution will taste much sweeter if you’ve just been tasting

something salty; a blast of room-temperature air will feel quite warm on your

skin if you’ve just come in from the cold.

The importance of change in

shaping our sensations shows up in many settings— including the phenomenon of sensory adaptation. This term refers to

the way our sen-sory apparatus registers a strong response to a stimulus when

it first arrives, but then gradually decreases that response if the stimulus is

unchanging. Thus, when we first walk into a restaurant, the smell of garlic is

quite noticeable; but after a few minutes, we barely notice it. Likewise, the

water may feel quite hot when you first settle into the bathtub; a few moments

later, the sensation of heat fades away.

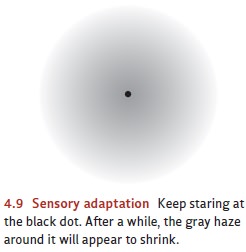

Sensory adaptation is easily

documented both in the lab and informally. Here’s an example: Stare at the dot

in the center of Figure 4.9, trying not to move your eyes at all. After 15 or

20 seconds, the gray haze surrounding the dot will probably appear to shrink

and may disappear altogether. (The moment you move your eyes, the haze is

restored.)

What’s happening in this case?

The gray haze is initially a novel stimulus, so it elic-its a strong response

from the visual system. After a moment or two, the novelty is gone; and, with

no change in the input, the response is correspondingly diminished. It’s

important for this demonstration, though, that the haze has an indistinct edge.

While looking at the figure, your eyes will tremble just a bit, so the image of

the haze will shift slightly from one position on your eye to another. But,

because the edge of the haze is blurred, these shifts will produce very little

change in the stimulation—so the haze slowly vanishes from view. (With more

sharply defined contours, small changes in eye position will cause large

changes in the visual input. As a result, even the slightest jit-ter in the eye

muscles will provide new information for the visual system. This helps us

understand why you can stare out the window for many minutes, or stare at a

computer screen, without the input seeming to vanish!)

What do organisms gain by this

sort of sensory adaptation? Stimuli that have been around for a while have

already been inspected; any information they offer has already been detected

and analyzed. It’s sensible, therefore, to give these already checked inputs

less sensory weight. The important thing is change—especially sudden

change—because it may well signify food to a predator and death to its

potential prey.

Related Topics