Chapter: Psychology: Sensation

The Origins of Knowledge

THE ORIGINS OF KNOWLEDGE

Where does human knowledge come

from? One possibility is that our knowledge comes directly from the world

around us, and that our eyes, ears, and other senses are simply collecting the

information the world provides. According to this view, our senses faithfully

receive and record information much as a camera receives light or a microphone

receives sound, and this implies that our perception of the world is a rela-tively

passive affair. After all, a camera doesn’t choose which light beams to

receive, nor does it interpret any of the light it detects. Instead, it simply

records the light available to it. Likewise, a microphone doesn’t interpret the

speech or appreciate the music; again, in a passive way, it simply receives the

sounds and passes them along to an amplifier or recording device. Could this be

the way our vision and hearing work?

The Passive Perceiver

Advocates for the philosophical

view known as empiricism argued that

our senses are passive in the way just described. One of the earliest

proponents of this position was the 17th-century English philosopher John

Locke. He argued that at birth, the human mind is much like a blank tablet—a tabula rasa, on which experience leaves

its mark (Figure 4.1).

Let us suppose the mind to be, as

we say, a white paper void of all characters, without any ideas:—How comes it

to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store which the busy and

boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety? Whence

has it all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one

word, from experience. In that all our knowledge is founded; and from that it

ultimately derives itself. (Locke, 1690)

To evaluate Locke’s claim,

however, we need to be clear about exactly what information the senses receive.

What happens, for example, when we look at another person? We’re presumably

interested in what the person looks like, who he is, and what he’s doing. These

are all facts about the distal stimulus—the

real object (in this case, the person) in the outside world. (The distal

stimulus is typically at some distance from the per-ceiver, hence the term distal.)

But it turns out that our

information about the distal stimulus is indirect, because we know the distal

stimulus only through the energies that actually reach us—the pattern of light

reflected off the person’s outer surface, collected by our eyes, and cast as an

image on the retina, the light-sensitive tissue at the rear of each eyeball.

This input— that is, the energies that actually reach us—is called the proximal (or “nearby”)stimulus.

The distinction between distal

and proximal stimuli is crucial for hearing as well as vision. We hear someone

speaking and want to know who it is, what she’s saying , and whether she sounds

friendly or hostile. These are all questions about the speaker herself, so they

’re questions about the distal stimulus. However, our percep-tion of these

points must begin with the stimulus that actually reaches us—the sound-pressure

waves arriving at our eardrums. These waves are the proximal stim-ulus for

hearing.

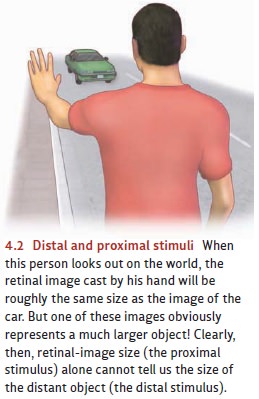

The distinction between distal

and proximal stimuli is a problem for empiricists. To see why, let’s look at

the concerns raised by another empiricist philosopher, George Berkeley. As

Berkeley pointed out, a large object that’s far away from us can cast the

same-size image on our retina as can a small object much closer to us (Figure

4.2). Retinal-image size, therefore, doesn’t tell us the size of the distal

object. How, then, do we tell the large objects in our world from the small?

Berkeley also knew that the retina is a two-dimensional sur-face, and that all

images—from near objects and far—are cast onto the same plane. He argued,

therefore, that the retinal image cannot directly inform us about the

three-dimen-sional world. Yet, of course, we have little difficulty moving

around the world, avoiding obstacles, grasping the things we want to grasp. How

can we explain these abilities in light of the limitations of proximal stimuli?

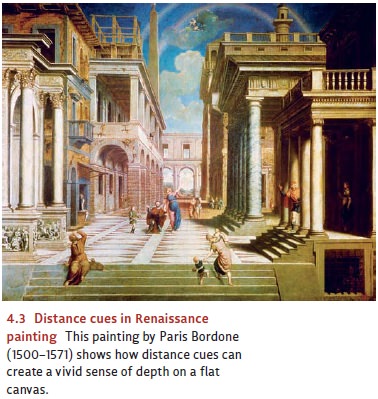

The empiricists’ answer to these

questions boils down to a single word: learning.

We can perceive and move around in the three-dimen-sional world, they argued,

because our experience has taught us

how to interpret the two-dimensional proximal stimulus. To see how this

interpretation unfolds, consider the role of depth cues contained within the retinal image. These cues include

what’s called visualperspective—a cue

used to convey depth in many paintings (Figure4.3). The empiricists argued

that, in many circumstances, we see the pattern of visual perspective and a

moment later reach for or walk toward the objects we’re viewing. This

experience creates an associa-tion in the mind between the visual cue and the

appropriate move-ment; and because this experience has been repeated over and

over, the visual cue alone now produces the memory of the movement and thus the

sense of depth. In this way, our perception is guided by the proximal stimulus and the association.

The Active Perceiver

Other philosophers soon offered a

response to the empiricist position, arguing that the perceiver plays a much

larger role than the empiricists realized. In this view, the perceiver does far

more than supplement the sensory input with associations. In addition—and more

important—the perceiver must categorize and interpret the incoming sensory

information.

Many scholars have endorsed this

general position, but it’s often attributed to the German philosopher Immanuel

Kant (1724–1804; Figure 4.4). Kant argued that per-ception is possible only

because the mind organizes the sensory information into cer-tain preexisting

categories. Specifically, Kant claimed that each of us has an innate grasp of

certain spatial relationships, so that we understand what it means for one

thing to be next to or far from another thing, and so on. We also

have an innate grasp of temporal relationships (what it means for one event to

occur before another, or after) as well as what it means for one

event to cause another. This basic understanding of space, time, and causality

brings order to our perception; without this framework, Kant argued, our

sensory experience would be chaotic and meaningless. We might detect the

individual bits of red or green or heavy or sour; but without the framework

supplied by each perceiver, we’d be unable to assemble a coherent sense of the

world.

Notice that, in Kant’s view,

these categories (Kant called them “forms of apperception”) are what make

perception possible; without the categories, there can be no perception. The

categories must be in place, therefore, before any perceptual experi-ence can

occur, so they obviously can’t be derived

from perceptual experience. Instead, they must be built into the very

structure of the mind, as part of our biological heritage.

Related Topics