Chapter: Psychology: Thinking

Problem Solving: Experts

Experts

Our discussion of creativity

draws attention to another crucial point: People plainly differ in their

ability to solve problems. Some people seem to be good problem solvers; others

are not. Some people often seem able to find new ways to approach a problem;

others invariably seem to rely on the procedures they’ve used in the past. What

should we make of these differences?

Different authors have suggested

a variety of perspectives on these points. Some writers emphasize innate

factors in explaining why some individuals are creative and others not, or why

some individuals seem especially successful in solving problems while others

seem less so. Other writers, in contrast, seek to explain the same points in

terms of the social or cultural context. (For a review of these diverse views,

see Sawyer, 2006.) There’s no question, though, that one factor is crucial:

experience working in a particular domain. Thus, the quality of a physician’s

problem solving (e.g., her ability to find accurate diagnoses) is improved

after many years of medical practice; the quality of an electrician’s problem

solving (the ability to troubleshoot a problem or lay out a com-plex wiring

pattern) is likewise enhanced by on-the-job experience. The same is true for

painters or professors or police officers—they all become better problem

solvers with experience.

But why exactly does experience

improve problem solving? Why does experience

turn someone into an expert? The

answer has several parts; but one crucial element lies in the fact that, over

their years of work, experts gather a wealth of information about their domain

of expertise—a database they can turn to in solving new problems. Indeed, this

is why several theorists have suggested that someone usually needs a full

decade to acquire expert status, whether the proficiency is in music, software

design, chess, or any other arena. Ten years is the time needed to acquire a

large enough knowledge base so that the expert has the necessary facts near at

hand and well cross-referenced, so that he can access them when needed (Bédard

& Chi, 1992; Ericsson, 1996; Hayes, 1985).

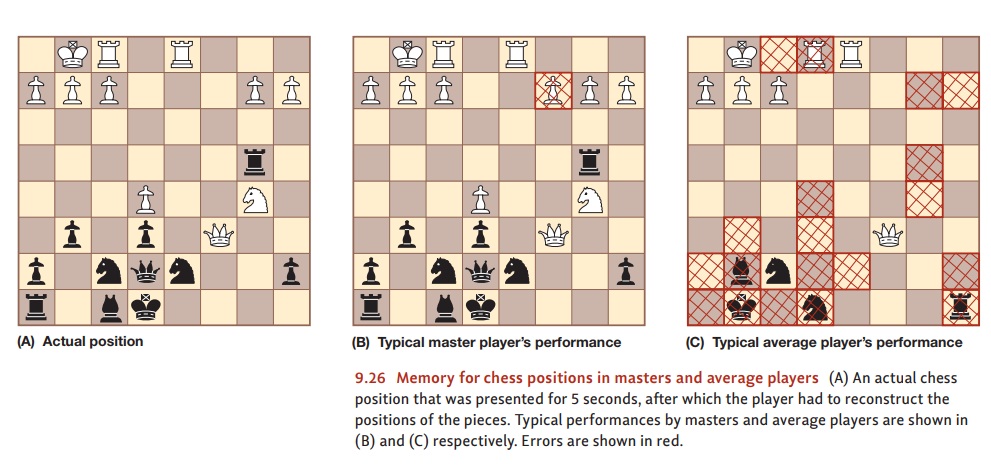

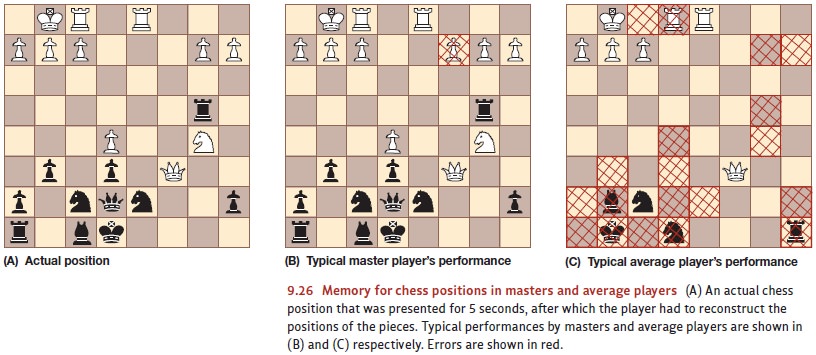

It’s important to be aware, though, that experts don’t just have more knowledge than novices do; they also have a different type of knowledge that is focused on higher-order patterns. This knowledge enables experts to think in larger units, tackling problems in big steps rather than small ones. This ability is evident, for example, in studies of chess players (Chase & Simon, 1973a, 1973b; de Groot, 1965). Novice chess players think about a game in terms of the position of individual pieces; experts, in contrast, think about the board in terms of pieces organized into broad strategic groupings (e.g., a king-side attack with pawns). This sort of thinking is made possible by the fact that chess masters have a “chess vocabulary” in which these complex concepts are stored as single memory chunks, each with an associated set of subroutines for how one should respond to that pattern. Some investigators estimate, in fact, that the masters may have as many as 50,000 of these chunks in their memories, each representing a strategic pattern (Chase & Simon, 1973b).

These memory chunks can be

detected in many ways, including the way players recall a game. In one study,

players of different ranks were shown chess positions for 5 seconds each and

then asked to reproduce the positions a few minutes later. Grandmasters and

masters did so with hardly an error; lesser players, however, made many errors

(Figure 9.26). This difference in performance wasn’t because chess masters had

better visual memory. When presented with bizarre positions that were unlikely

ever to arise in the course of a game, the chess masters recalled them no

better than novices did—and in some cases, they remembered the bizarre patterns

less accurately than did novices

(Gobet & Simon, 1996a, 1996b; but also see Gobet & Simon, 2000;

Lassiter, 2000). The superiority of the masters, therefore, was in their

conceptual organization of chess, not in their memory for patterns as such.

Experts’ sensitivity to a

problem’s organization can also be demonstrated in other ways. For example,

intro-level physics students tend to group problems in terms of their surface

characteristics, so they might group together all the problems involving

springs or all the problems involving inclined planes. Experts, in contrast,

instantly perceive the deeper structure of each problem; so they group problems

not according to surface features, but according to the physical principles

relevant to each problem’s solution. Clearly, then, the experts are more

sensitive to the higher-order patterns, and this calls their attention to the

strategies needed for solving the problem (Chi, Feltovich, & Glaser, 1981;

also Cummins, 1992; Reeves & Weisberg, 1994).

Finally, this knowledge of

higher-order patterns also helps experts in another way. We’ve already said

that analogies are a powerful aid to problem solving, but that people often

fail to detect, or make use, of analogies. Experts, in contrast, routinely draw

on analogies; and this gives them a huge advantage in their work. In fact, the

experts’ use of analogies is almost inevitable. We’ve already noted that analogy

use is promoted by attention to a problem’s underlying structure, rather than

its surface characteristics. We’ve also said that an expert’s knowledge is

generally cast in terms of higher-order

patterns that are typically

defined in terms of the cause-and-effect structure within a problem. If we put

these pieces together, it seems that experts have exactly the right

per-spective to make analogy use highly probable—and so it’s entirely sensible

that they frequently benefit from this problem-solving tool.

Related Topics