Chapter: Psychology: Thinking

Judgment: The Representativeness Heuristic

The

Representativeness Heuristic

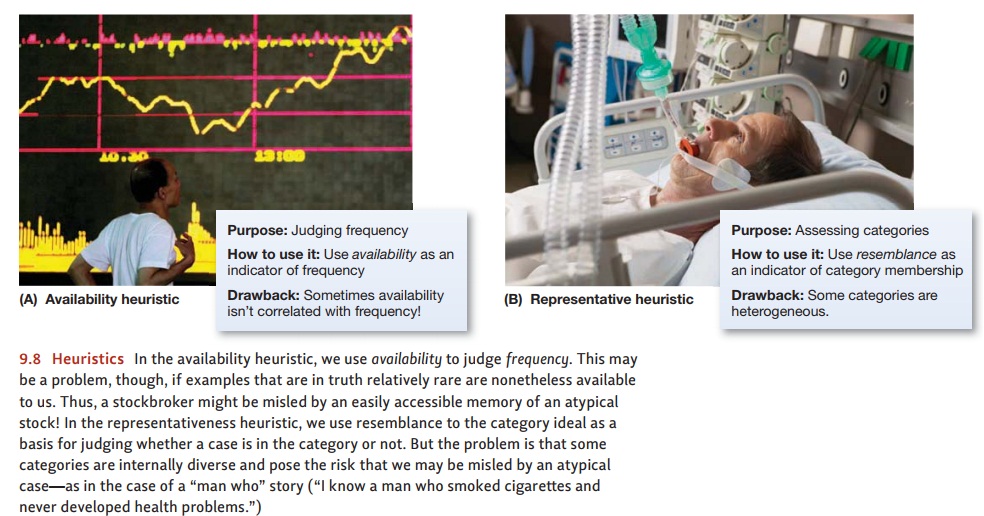

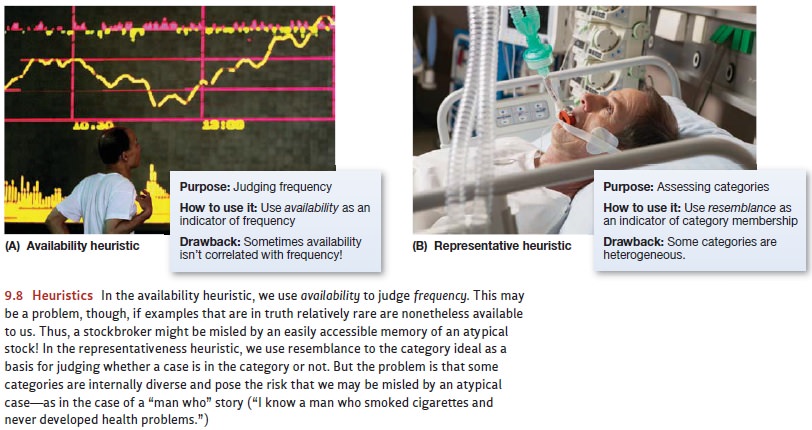

When our judgments hinge on

frequency estimates, we rely on the availability heuris-tic. Sometimes, though,

our judgments hinge on categorization,

and then we turn to a different heuristic (Figure 9.8). For example, think

about Marie, who you met at lunch yesterday. Is she likely to be a psychology

major? If she is, you can rely on your broader knowledge about psych majors to

make some forecasts about her—what sorts of con-versations she’s likely to

enjoy, what sorts of books she’s likely to read, and so on.

If during lunch you asked Marie

what her major is, then you’re all set—able to apply your knowledge about the

category to this particular individual. But what if you didn’t ask her about

her major? You might still try to guess her major, relying on the representative-ness heuristic. This is

a strategy of assuming that each member of a category is “represen-tative” of

the category—or, said differently, a strategy of assuming that each category is

relatively homogeneous, so that every member of the category resembles every

other mem-ber. Thus, if Marie resembled other psych majors you know (in her

style of conversation, or the things she wanted to talk about), you’re likely

to conclude that she is in fact a psych major—so you can use your knowledge

about the major to guide your expectations for her.

This strategy—like the availability heuristic—serves us well in many settings, because many of the categories we encounter in our lives are homogeneous in important ways.

People don’t vary much in the

number of fingers or ears we have. Birds uniformly share the property of having

wings and beaks, and hotel rooms share the property of having beds and

bathrooms. This uniformity may seem trivial, but it plays an enormously

important role: It allows us to extrapolate from our experiences, so that we

know what to expect the next time we see a bird or enter a hotel room.

Even so, evidence suggests that

we overuse the representativeness

strategy, extrapo-lating from our experiences even when it’s clear we should

not. This pattern is evident, for example, whenever someone offers a “man who”

or “woman who” argument: “What do you mean, cigarettes cause cancer? I have an

aunt who smokes cigarettes, and she’s perfectly healthy at age 82!” Such

arguments are often presented in conversations as well as in more formal

settings (political debates, or newspaper editorial pages), pre-sumably relying

on the listener’s willingness to generalize from a single case. What’s more,

these arguments seem to be persuasive: The listener (to continue the example)

seems to assume that the category of all cigarette smokers is uniform, so that

any one member of the category (including the speaker’s aunt) can be thought of

as representa-tive of the entire group. As a result, the listener draws

conclusions about the group based on this single case—even though a moment’s

reflection might remind us that the case may be atypical, making the

conclusions unjustified.

In fact, people are willing to

extrapolate from a single case even when they’re explic-itly warned that the

case is an unusual one. In one study, participants watched a video-taped

interview with a prison guard. Some participants were told in advance that the

guard was quite atypical, explicitly chosen for the interview because he held

such extreme views. Others weren’t given this warning. Then, at the end of the

videotape, participants were asked their own views about the prison system, and

their responses showed a clear influence from the interview they had just seen.

If the interview had shown a harsh, unsympathetic guard, participants were

inclined to believe that, in gen-eral, prison guards are severe and inhumane.

If the interview showed a compassionate,

caring guard, participants

reported more positive views of the prison system. Remarkably, though,

participants who had been told clearly that the guard was atypical were just as

willing to draw conclusions from the video as the participants given no

warning. Essentially, participants’ reliance on the representativeness

heuristic made the warning irrelevant (Hamill, Wilson, & Nisbett, 1980; Kahneman

& Tversky, 1972, 1973; Nisbett & Ross, 1980).

Related Topics