Chapter: Psychology: Thinking

Problem Solving: The Role of the Goal State

The Role of the

Goal State

Imagine that you’re trying to

locate a job, so that you’ll be able to pay the rent in the coming months. One

option is just to let your thoughts run: “Job” might remind you of “money,”

which would remind you of “bank,” which would make you think about “bank

tellers” and perhaps lead you to think that’s the job you want. This sort of

prob-lem solving, which relies on a process of free association, surely does

occur. But far more often, you rely on a more efficient strategy—guided not

just by your starting point (technically: your initial state) but also by your understanding of the goal state. Said dif-ferently, your

thoughts in solving a problem are guided both by where you are and where you

hope to be.

The importance of the goal state

shows up in many aspects of problem solving, including the different ways

people approach well-defined problems and ill-defined problems. A well-defined problem is one in which you

have a clear idea of the goal right at the start, and you also know what

options are available to you in reaching that goal. One example is an anagram

problem: What English word can be produced by rearrang-ing the letters subufoal? Here you know immediately that

the goal will involve just these eight letters and will be a word in the

English language; you know that you’ll reach that goal by changing the sequence

of the letters (and not, for example, by turning letters upside down).

With a problem like this one,

your understanding of the goal guides you in impor-tant ways. Thus, you won’t

waste time adding extra letters or turning some of the letters into numerals;

those steps, you already know, are incompatible with your goal. You also won’t

try rewriting the word in a different font or in a different color of ink.

Those steps are simply irrelevant for your goal. (The solution to this anagram,

by the way, is fabu-lous; other

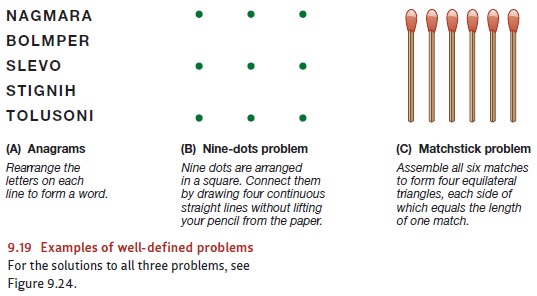

examples of well-defined problems are shown in Figure 9.19.)

For an ill-defined problem, in contrast, you start the problem with only a

hazy sense of the goal. For example, imagine you’re trying to find something

fun to do next sum-mer, or you’re trying to think of ways we might achieve

world peace. For problems like these, you know some of the properties of the

goal state (e.g., “fun,” and “no war”) but there are many things you don’t

know: Will you find your summer fun at home, or trav-eling? Will we achieve

peace through diplomacy? Through increased economic interde-pendence? How?

If a problem is ill defined, the goal itself provides only loose guidance for your problem solving. It’s no surprise, therefore, that people usually try to solve ill-defined problems by first making them well defined—that is, by seeking ways to clarify and specify the goal state. In many cases, this effort involves adding extra constraints or extra assumptions (“Let me assume that my summer of fun will involve spending time near the ocean,” or “Let me assume that my summer travel can’t cost more than $500”). This narrows the set of options—and conceivably may hide the best options from view—but for many problems, defining the problem more clearly helps enormously in the search for a solution (Schraw, Dunkle, & Bendixen, 1995).

Related Topics