Chapter: Psychology: Thinking

Problem Solving: Overcoming Obstacles to Solutions

Overcoming

Obstacles to Solutions

If problem-solving sets can

sometimes cause difficulties, then we want to ask: How can these sets be

overcome? Similarly, we’ve emphasized the importance of subgoals and familiar

routines, but what can we do if we fail to perceive the subgoals or are

unfamil-iar with the relevant routine?

A number of strategies are

helpful when people are stuck on a difficult problem, but one of the most

useful is to rely on an analogy. In

other words, you can often solve a problem by recalling some previous, similar

problem and applying its solution (or a minor variation on it) to your current

problem. Thus, a business manager might solve today’s crisis by remembering how

she dealt with a similar crisis just a few months back. A psychotherapist might

realize how to help one patient by recalling his approach to a similar patient

a year ago.

Analogies turn out to be enormously

helpful in many settings. They’re useful as a form of instruction, and so students gain understanding of how gas

molecules function by thinking about how the balls bump into each other on a

pool table; they learn about memory by comparing it to a vast library.

Analogies are also a powerful source of discov-eries,

and so (for example) scientists expanded their understanding of the heart,

yearsago, by comparing it to a pump (Gentner & Jeziorski, 1989). And, of

course, analogies are also helpful in solving problems. In one study (Gick

& Holyoak, 1980), for example, participants were given this problem:

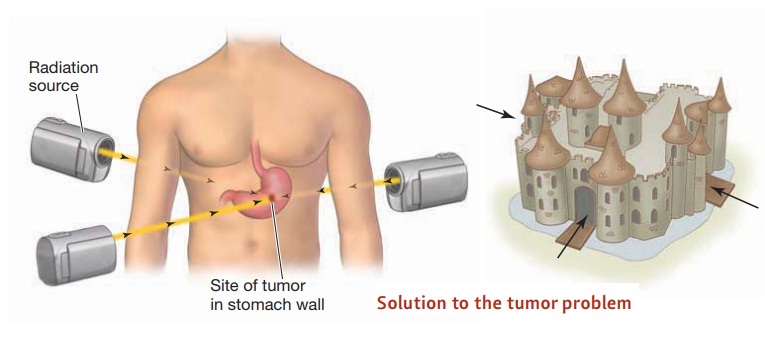

Suppose a patient has an

inoperable stomach tumor. There are certain rays that can destroy this tumor if

their intensity is great enough. At this intensity, however, the rays will also

destroy the healthy tissue that surrounds the tumor (e.g., the stomach walls,

the abdominal muscles, and so on). How can the tumor be destroyed without

damaging the healthy tissue through which the rays must travel on their way?

The problem is difficult; and in

this experiment, 90% of the participants failed to solve it. A second group,

however, did much better. Before tackling the tumor problem, they read a story

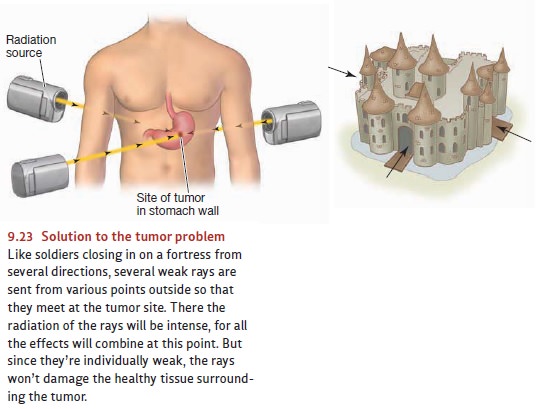

about a general who hoped to capture a fortress. He needed a large force of

soldiers for this, but all of the roads leading to the fortress were planted

with mines. Small groups of soldiers could travel the roads safely, but the

mines would be detonated by a larger group. How, therefore, could the general

move all the soldiers he would need toward the fortress? He could do this by

dividing his army into small groups and send-ing each group via a different

road. When he gave the signal, all the groups marched toward the fortress,

where they converged and attacked successfully.

The structure of the fortress

story is similar to that of the tumor problem. In both cases, the solution is

to divide the “conquering” force so that it enters from several dif-ferent

directions. Thus, to destroy the tumor, several weak rays can be sent through

the body, each from a different angle. The rays converge at the tumor,

inflicting their com-bined effects just as desired (Figure 9.23).

With no hints or analogies to

draw on, only 10% of the participants were able to solve the tumor problem.

However, if they were given the fortress story and told that it would help

them, most (about 80%) did solve it. Obviously, the analogy was quite help-ful.

But just knowing the fortress story wasn’t enough; participants also had to

realize that the story was pertinent to the task at hand—and, surprisingly,

they often failed to make this connection. In another condition, participants

read the fortress story but were given no indication that this story was

relevant to their task. In that case, only 30% solved the tumor problem (Gick

& Holyoak, 1980, 1983).

Clearly, analogies are helpful. Even so, people often fail to use them, even if the plau-sible analogue is available in their memory. Is there anything we can do, therefore, to encourage the use of analogies? It turns out that there is. Evidence suggests, for exam-ple, that people are more likely to use analogies if they’re encouraged to focus on the underlying dynamic of the problem (e.g., the fortress problem involves converging forces) rather than its superficial features (e.g., the problem involves mines). This focus on the underlying dynamic calls attention to the features shared by the problems, help-ing people to see the relevance of the analogies and enabling them to map one problem onto another (Blanchette & Dunbar, 2000; Catrambone, 1998; Cummins, 1992; Dunbar & Blanchette, 2001; Needham & Begg, 1991).

Related Topics