Chapter: Embedded Systems

Multiple Tasks and Multiple Processes

PROCESSES AND OPERATING SYSTEMS

■The

process abstraction.

■Switching

contexts between programs. ■Real-time operating systems(RTOSs).

■ Inter

process communication.

■Task-level

performance analysis and power consumption.

■A

telephone answering machine design.

We are

particularly interested in real-time operating systems (RTOSs), which are Oss that

provide facilities for satisfying real-time requirements. ARTOS allocates

resources using algorithms that take real time in to account. General-purpose

OSs, incontrast, generally allocate resources using other criteria like

fairness. Trying to allocate the CPU equally to all processes with out regard

to time can easily cause processes to miss their deadlines. In the next

section, we will introduce the concepts of task and process. Introduces some

basic concepts in inter process communication. Section6.5con- siders the

performance of RTOSs while Section6.6 looks at power consumption. Section 6.7

walks through the design of a telephone answering machine.

MULTIPLE TASKS AND MULTIPLE PROCESSES

Most

embedded systems require functionality and timing that is too complex to body

in a single program. We break the system in to multiple tasks in order to

manage when things happen. In this section we will develop the basic

abstractions that will be manipulated by the RTOS to build multirate systems.

To understand why these parathion of an application in to tasks may be

reflected in the program structure, consider how we would build a stand-alone

compression unit based on the compression algorithm we implemented in

Section3.7. As shown in Figure6.1, this device is connected to serial ports on

both ends. The input to the box is an uncompressed stream of bytes. The box

emits a compressed string of bits on the output serial line, based on a

predefined compression table. Such a box may be used, for example, to compress

data being sent to a modem. The program’s need to receive and send data at

different rates—for example, the program may emit 2 bits for the first byte and

then 7 bits for the second byte— will obviously find itself reflected in the

structure of the code. It is easy to create irregular, ungainly code to solve

this problem; a more elegant solution is to create a queue of out put bits,

with those bits being removed from the queue and sent to the serial port in

8-bit sets. But beyond the need to create a clean data structure that

simplifies the control structure of the code, we must also ensure

that we

process the inputs and outputs at the proper rates. For example, if we spend

too much time in packaging and emitting output characters, we may drop an input

character. Solving timing problems is a more challenging problem.

The text

compression box provides a simple example of rate control problems. A control

panel on a machine provides an example of a different type of rate con- troll

problem, the asynchronous input. The control panel of the compression box may,

for example, include a compression mode button that disables or enables com-

pression, so that the input text is passed through unchanged when compression

is disabled. We certainly do not know when the user will push the compression

modebutton— the button may be depressed a synchronously relative to the arrival

of characters for compression. We do know, however, that the button will be

depressed at a much lower rate than characters will be received, since it is

not physically possible for a person to repeatedly depress a button at even

slow serial line rates. Keeping up with the input and output data while

checking on the button can introduce some very complex control code in to the

program. Sampling the button’s state too slowly can cause the machine to miss a

button depression entirely, but sampling it too frequently and duplicating a

data value can cause the machine to in correctly compress data.

One

solution is to introduce a counter in to the main compression loop, so that a

subroutine to check the input button is called once every times the compression

loop is executed. But this solution does not work when either the compression

loop or the button-handling routine has highly variable execution times—if the

execution time of either varies significantly, it will cause the other to

execute later than expected, possibly causing data to be lost. We need to be

able to keep track of these two different tasks separately, applying different

timing requirements to each.

This is

the sort of control that processes allow. The above two examples illustrate how

requirements on timing and execution rate can create major problems in

programming. When code is written to satisfy several different timing

requirements at once, the control structures necessary to get any sort of

solution become very complex very quickly. Worse, such complex control is

usually quite difficult to verify for either functional or timing properties.

Multi rate Systems

Implementing

code that satisfies timing requirements is even more complex when multiple

rates of computation must be handled. Multi rate embedded computing systems are

very common, including auto mobile engines, printers, and cell phones.In all

these systems, certain operations must be executed periodically, and each

oper-ation is executed at its own rate. Application Example6.1 describes why

auto mobile engines require multi rate control.

Timing Requirements on Processes

Processes

can have several different types of timing requirements imposed on them by the

application. The timing requirements on a set of process strongly influence the

type of scheduling that is appropriate. A scheduling policy must define the

timing requirements that it uses to determine whether a schedule is valid.

Before studying scheduling proper, we outline the types of process timing

requirements that are useful in embedded system design. Figureillustrates

different ways in which we can define two important requirements on processes:

eg. What happens when a process misses a deadline? The practical effects of a

timing violation depend on the application—the results can be catastrophic in

an auto mo- tive control system, where as a missed deadline in a multi media

system may cause an audio or video glitch. The system can be designed to take a

variety of actions when a deadline is missed. Safety-critical systems may try

to take compensatory measures such as approximating data or switching in to a

special safety mode. Systems for which safety is not as important may take

simple measures to avoid propagating bad data, such as inserting silence in a

phone line, or may completely ignore the failure.Even if the modules are

functionally correct, their timing improper behavior can introduce major

execution errors. Application Example6.2 describes a timing problem in space

shuttle software that caused the delay of the first launch of the shuttle. We

need a basic measure of the efficiency with which we use the CPU. The simplest

and most direct measure is utilization:

Utilization

is the ratio of the CPU time that is being used for useful computations to the

total available CPUtime. This ratio ranges between 0 and 1, with 1 meaning that

all of the available CPU time is being used for system purposes. The

utilization is often expressed as a percentage. If we measure the total

execution time of all processes over an interval of time t, then the CPU

utilization is U/T

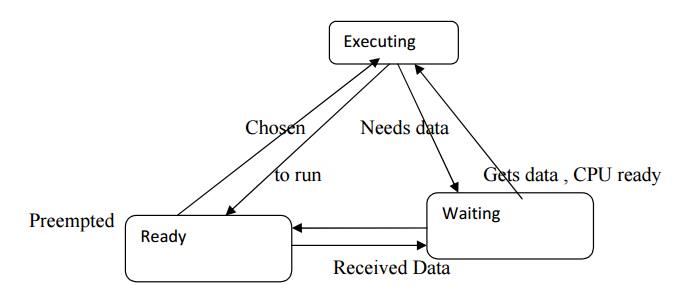

Process State and Scheduling

The first

job of the OS is to determine that process runs next. The work of choosing the

order of running processes is known as scheduling. The OS considers a process

to be in one of three basic scheduling states

Schedulability means whether there exists a schedule of execution for the processes in a system that satisfies all their timing requirements. In general, we must construct a schedule to show schedulability, but in some cases we can eliminate some sets of processes as unschedulable using some very simple tests. Utilization is one of the key metrics in evaluating a scheduling policy. Our most basic require- ment is that CPU utilization be no more than 100% since we can’t use the CPU more than100% of the time.

When we

evaluate the utilization of the CPU, we generally do so over a finite period

that covers all possible combinations of process executions. For periodic

processes, the length of time that must be considered is the hyper period,

which is the least-common multiple of the periods of all the processes. If we

evaluate the hyper period, we are sure to have considered all possible

combinations of the periodic processes. The next example evaluates the

utilization of a simple set of processes.

We will

see that some types of timing requirements for a set of processes imply that we

can not utilize 100% of the CPU’s execution time on useful work, even ignoring

context switching overhead. However, some scheduling policies can deliver

higher CPU utilizations than others, even for the same timing requirements. The

best policy depends on the required timing characteristics of the processes

being scheduled.

On every

simple scheduling policy is known as cyclostatic scheduling or some- times as

Time Division Multiple Access scheduling. Processes always run in the same time

slot. Two factors affect utilization: the number of times lots used and the

fraction of each time slot that is used for useful work. Depending on the

deadlines for some of the processes, we may need to leave some times lots

empty. And since the time slots are of equal size, some short processes may

have time left over in their time slot. We can use utilization as a

schedulability measure: the total CPU time of all the processes does not have

any useful work to do, the round-robin scheduler moves on to the next process

in order to fill the time slot with useful work. In this example, all three

processes execute during the first hyper period, but during the second one, P1

has no useful work and is skipped. The processes are always evaluated in the

same order. The last time slot in the hyper period is left empty; if we have

occasional, non-periodic tasks with out deadlines, we can execute them in these

empty time slots. Round-robin scheduling is often used in hardware such as

buses because it is

Very

simple to implement but it provides some amount of flexibility. In addition to

utilization, we must also consider scheduling overhead—the execution time

required to choose the next execution process, which is incurred in addition to

any context switch in gover head. In general, the more sophisticated the scheduling

policy, the more CPU time it takes during system operation to implement it.

Moreover, we generally achieve higher theoretical CPU utilization by applying

more complex scheduling policies with higher over heads. The final decision on

a scheduling policy must take in to account both theoretical utilization and

practical scheduling overhead.

Running Periodic Processes

We need

to find a programming technique that allows us to run periodic processes,

ideally at different rates. For the moment, let’s think of a process as a

subroutine; we will call the mp1(), p2(), etc. for simplicity. Our goal is to

run these subroutines at rates determined by the system

designer.

Here is a very simple program that runs our process subroutines repeatedly: A

timer is a much more reliable way to control execution of the loop. We would

probably use the timer to generate periodic interrupts. Let’s assume for the

moment that the pall() function is called by the timer’s interrupt handler.

Then this code will execute each process once after a timer interrupt:

voidpall()

{

p1();

p2();

}

But what

happens when a process runs too long? The timer’s interrupt will cause the

CPU’s interrupt system to mask its interrupts, so the interrupt will not occur

until after the pall() routine returns. As a result, the next iteration will

start late. This is a serious problem, but we will have to wait for further

refinements before we can fix it.

Our next

problem is to execute different processes at different rates. If we have

several timers, we can set each timer to a different rate. We could then use a

function to collect all the processes that run at that rate:

voidpA()

{

/*processesthatrunatrateA*/

p1();

p3();

}

voidpB()

{

/*processesthatrunatrateB*/

This

solution allows us to execute processes at rates that are simple multiples of

each other. However, when the rates are n’t related by a simple ratio, the

counting process becomes more complex and more likely to contain bugs. We have

developed some what more reliable code, but this programming style is still

limited in capability and prone to bugs. To improve both the capabilities and

reliability of our systems, we need to invent the RTOS.

Related Topics