Chapter: Psychology: The Brain and the Nervous System

The Organism as a Machine

THE ORGANISM AS

AMACHINE

The idea that human behaviors,

thoughts, and feelings are a product of the brain

is usually attributed to the philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650; Figure

3.1). Before Descartes’ time, people in the Western world generally regarded

human behavior as complex and mysterious but, in any case, best understood as

the result of the soul’s directives and certainly not the product of some mere

machinery.

Descartes’ new perspective,

however, was encouraged by the times in which he lived. After all, the 1500s

and 1600s saw enormous scientific advances: Kepler and Galileo were devel-oping

ideas about the movements of the stars and planets visible in the night sky,

and their observations were part of the intellectual growth that led to Isaac

Newton’s formulation of the laws of motion, summarized in 1687 in his

extraordinary book Principia Mathematica.

These new views of the universe suggested that natural phenomena could be

understood through relatively straightforward principles of acceleration,

inertia, and momentum—prin-ciples that could be described precisely with simple

mathematical laws. These laws, in turn, could explain a huge range of

phenomena—from the drop of a stone to the motions of plan-ets. Indeed, the same

laws could be seen operating—rigidly, immutably—in the workings of ingenious mechanical

contrivances that were all the rage in the wealthy homes of Europe: cuckoo

clocks that sounded on the hour, water-driven gargoyles with nodding heads,

statues in the king’s garden that bowed to visitors who stepped on hidden

springs. The turning of a gear, the release of a spring—these simple mechanisms

could cause all kinds of clever effects.

With these intellectual and

technical developments in place, and with so many complex events that could be

explained in such simple terms, it was only a matter of time before someone

asked the crucial question: Could human actions be explained just as

mechanically?

Descartes’ answer to this

question, as well as his view of action in general (whether the action of a

human or some other animal), was radical and straightforward. He proposed that

every action by an organism is a direct response to some event in the world:

Something from the outside excites one of the senses; this, in turn, excites a

nerve that transmits the excitation to the brain, which then diverts the

excitation to a muscle and makes the muscle contract. In effect, the energy

from the outside is “reflected” by the nervous system back to the animal’s

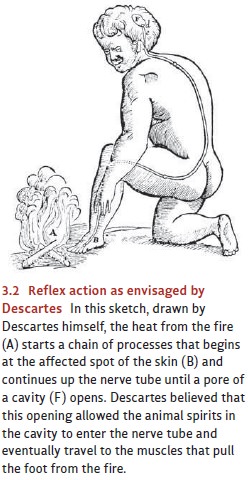

muscles, a conception that gave rise to the term reflex (Figure 3.2).

Seen in this light, human and

animal actions can certainly be regarded as the doings of a machine. But

Descartes also understood that he needed some account of the flexibility in our behavior. After all,

the sight of food might trigger an action of reaching toward the food if we are

hungry, but it triggers no action at all if we’re not. In Descartes’ terms,

therefore, it seemed that excitation from the senses could be reflected to one

set of muscles on one occasion and to an entirely different set on another—as

though the reflex mechanisms included some sort of central switching system

that controlled which incoming signal triggered which outgoing one.

How could Descartes explain this

switching system? He knew that a strictly mechani-cal explanation would have

unsettling theological implications: If all human action was caused by some

sort of machinery, what role was left for the soul? Descartes also knew that

Galileo had been condemned by the Inquisition because his scientific beliefs

threatened the doctrines of the Catholic Church. Perhaps it’s no surprise,

then, that Descartes pro-posed that the centralized controller of human

behavior was not a machine at all. Many processes within the brain, he argued,

did function mechanically; but what truly governed our behavior, what made reason

and choice possible, and what distinguished us from other animals, was the soul—operating through the brain,

choosing among nervous path-ways, and controlling our bodies like a puppeteer

pulling the strings on a marionette.

In the following decades, though,

theology’s grip on science loosened and other thinkers went further. They

believed that the laws of the physical universe could ultimately explain all

action, whether human or animal, so that a scientific account required no

further “ghost in the machine”—that is, no reference to the soul. They

therefore extended Descartes’ logic to all of human functioning, arguing that

humans differ from other animals only in being more finely constructed

mechanisms.

Of course, the ultimate question

of whether humans are just machines is as much a ques-tion about faith as it is

about science. In Descartes’ time, this question centered on whether our

behavior could be explained entirely in terms of fluid pressures or gears; in

more mod-ern terms, this question focuses on whether our behavior can be

explained entirely in terms of chemical and electrical signals within the

brain. In either case, the problem is the same: No one has the slightest idea

of how to test for the existence of an intangible soul; thus, the question of

whether we are machines, or machines with souls, is not something that can be

determined by science. Even so, no one can deny that the strategy of regarding

humans as machines—omitting all mention of a soul in our scientific

theorizing—has fostered dramatic breakthroughs in understanding ourselves and

our fellow animals.

Related Topics