Chapter: Psychology: The Brain and the Nervous System

The Anatomy of the Brain

The Anatomy of

the Brain

The peripheral nervous system is

crucial. Without it, no motion of the body would be possible; no information

would be received about the external world; the body would be unable to control

its own digestion or blood circulation. Still, the aspect of the nervous system

most interesting to psychologists is the central nervous system. It’s here that

we find the complex circuitry crucial for perception, memory, and thinking.

It’s the CNS that contains the mechanisms that define each person’s

personality, control his or her emotional responses, and more.

The CNS, as we’ve seen, includes

the spinal cord and the brain itself. The spinal cord, for most of its length,

actually does look like a cord; it has separate paths for nerves carrying

afferent information (i.e., information arriving

in the CNS) and nerves carrying efferent commands (information exiting the CNS). Inside the head, the

spinal cord becomes larger and looks something like the cone part of an ice

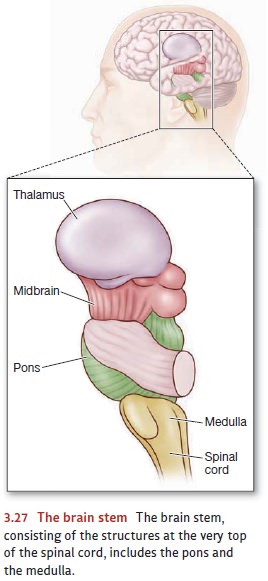

cream cone. Structures at the very top of the cord—looking roughly like the ice

cream on top of the cone—form the brain

stem (Figure 3.27). The medulla is

at the bottom of the brain stem; among its other roles, the medulla controls

our breathing and blood circulation. It also helps us maintain our balance by

controlling head orientation and limb positions in relation to gravity. Above

the medulla is the pons, which is one

of the most

important brain areas for

controlling the brain’s overall level of attentiveness and helps govern the

timing of sleep and dreaming.

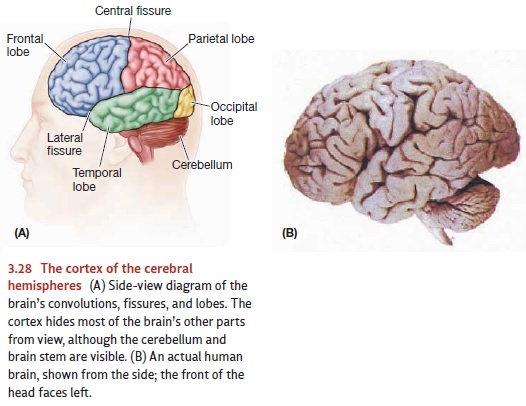

Just behind the brain stem is the

cerebellum (Figure 3.28A). For many

years, inves-tigators believed the cerebellum’s main role was to control

balance and coordinate movements—especially rapid and carefully timed

movements. Recent studies confirm this role, but suggest that the cerebellum

also has a diverse set of other functions. Damage to this organ can cause

problems in spatial reasoning, in discriminating sounds, and in integrating the

input received from various sensory systems (J. Bower & Parsons, 2003).

Sitting on top of the pons are

two more structures—the midbrain and thalamus (see Figure 3.27). Both of

these structures serve as relay stations directing information to the

forebrain, where the information is more fully processed and interpreted. But

these structures also have other roles. The midbrain, for example, helps

regulate our experience of pain and plays a key role in modulating our mood as

well as shaping our motivation.

On top of these structures is the

forebrain—by far the largest part of

the human brain. Indeed, photographs of the brain (Figure 3.28B) show little

other than the forebrain because this structure is large enough in humans to

surround most of the other brain parts and hide them from view. Of course, we

can see only the outer sur-face of the forebrain in such pictures; this is the cerebral cortex (cortex is the Latin word for “tree bark”).

The cortex is just a thin

covering on the outer surface of the brain; on average, it is a mere 3 mm

thick. Nonetheless, there is a great deal of cortical tissue; by some

estimates, the cortex constitutes 80% of the human brain (Kolb & Whishaw,

2009). This consider-able volume is made possible by the fact that the cortex,

thin as it is, consists of a very large sheet of tissue; if stretched out flat,

it would cover roughly 2.7 square feet (2,500 cm2). But the cortex

isn’t stretched flat; instead, it’s crumpled up and jammed into the limited

space inside the skull. This crumpling produces the brain’s most obvious visual

feature—the wrinkles, or convolutions, that cover the brain’s outer surface.

Some of the “valleys” in between

the wrinkles are actually deep grooves that divide the brain into different

anatomical sections. The deepest groove is the longitudinal fissure, run-ning from the front of the brain to the

back and dividing the brain into two halves— specifically, the left and the

right cerebral hemispheres. Other

fissures divide the cortex in each hemisphere into four lobes, named after the

bones that cover them—bones that, as a group, make up the skull. The frontal lobes form the front of the

brain, right behind the forehead. The central

fissure divides the frontal lobes on each side of the brain from the parietal lobes, the brain’s topmost

part. The bottom edge of the frontal lobes is marked bythe lateral fissure, and below this are the temporal lobes. Finally, at the very back of the brain—directly

adjoining the parietal and temporal lobes—are the occipital lobes.

As we’ll see, the cortex—the

outer surface of all four lobes—controls many func-tions. Because these

functions are so important to what we think, feel, and do, we’ll address them

in detail in a later section. But the structures beneath the cortex are just as

important. One of these is the hypothalamus,

positioned directly under-neath the thalamus and crucially involved in the

control of motivated behaviors such as eating , drinking , and sexual activity

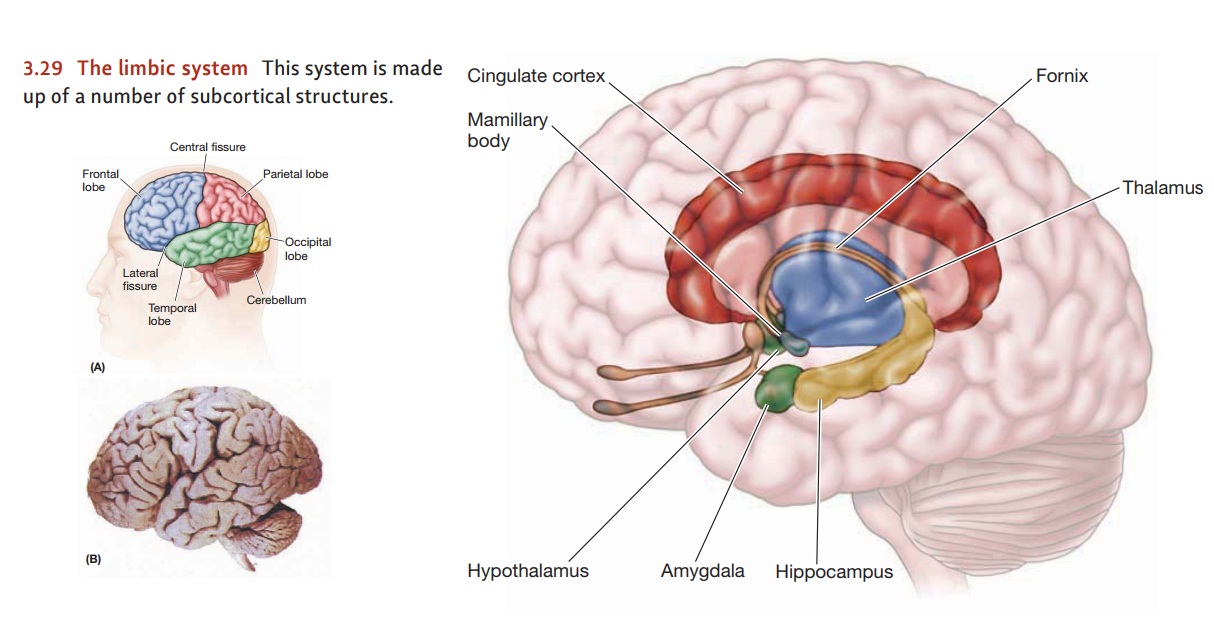

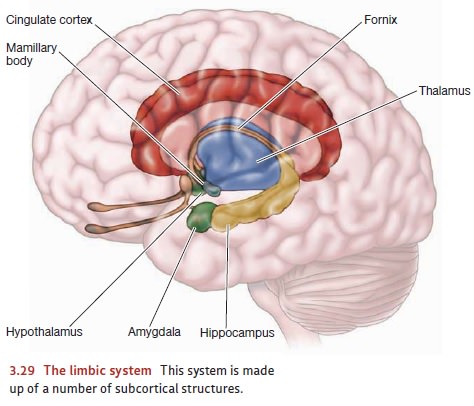

. Surrounding the thal-amus and hypothalamus is a set of interconnected

structures that form the limbicsystem (Figure

3.29). This system—especially one of its parts, the amygdala—plays a key role in modulating our emotional reactions

and seems to serve roughly as an “evaluator ” that helps determine whether a stimulus

is a threat or not, famil-iar or not, and so on. Nearby is the hippocampus, which is pivotal for

learning and memory as well as for our navigation through space. (In some

texts, the hippocam-pus is considered part of the limbic system, following an

organization scheme laid down more than 50 years ago. More recent analyses,

however, indicate that this ear-lier scheme is anatomically and functionally

misleading. For the original scheme, see MacLean, 1949, 1952; for a more recent

perspective, see Kotter & Meyer, 1992; LeDoux, 1996.)

Related Topics