Chapter: Psychology: The Brain and the Nervous System

Lateralization

Lateralization

The entire human brain is more or

less symmetrical around the midline, so there’s a thalamus on the left side of

the brain and another on the right. There’s also a left-side amygdala and a

right-side one. Of course, the same is true for the cortex itself: There’s a

temporal cortex in the left hemisphere and another in the right, a left

occipital cortex and a right one, and so on. In almost all cases—cortical and

subcortical—the left and right structures have roughly the same shape, the same

position in their respective sides of the brain, and the same pattern of

connections to other brain areas. Even so, there are some anatomical

distinctions between the left-side and right-side structures. We can also

document differences in function, showing that the left-hemisphere structures

play a somewhat different role from the corresponding right-hemisphere

structures.

The asymmetry in function between

the two brain halves is called lateralization,

and its manifestations influence phenomena that include language use and the

per-

ception and understanding of

spatial organization (Springer & Deutsch, 1998). Still, it’s important to

realize that the two halves of the brain, each performing somewhat different

functions, work closely together under almost all circumstances. This

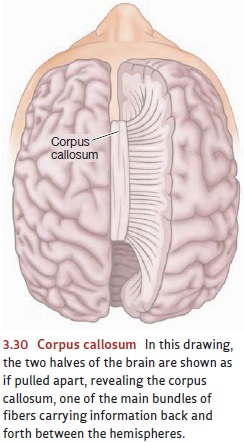

inte-gration is made possible by the commissures—thick

bundles of fibers that carry infor-mation back and forth between the two

hemispheres. The largest and probably most important commissure is the corpus callosum, but several other

structures also ensure that the two brain halves work together as partners in

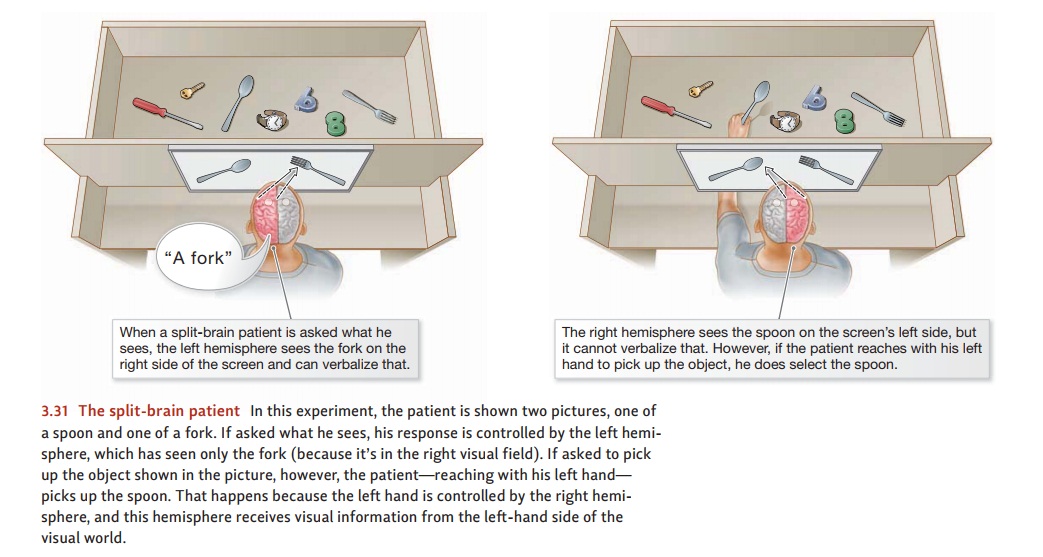

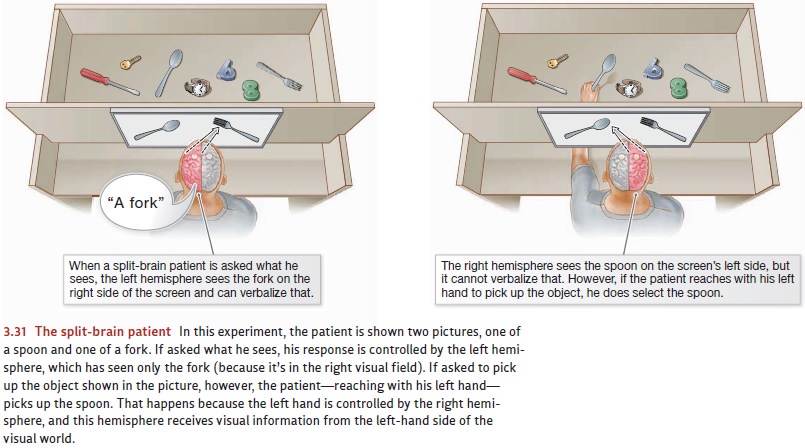

virtually all mental tasks (Figure 3.30).

In some people, these

neurological bridges between the hemispheres have been cut for medical reasons.

This was, for example, a last-resort treatment for many years in cases of

severe epilepsy. The idea was that the epileptic seizure would start in one

hemisphere and spread to the other, and this spread could be prevented by

disconnect-ing the two brain halves from each other (Bogen, Fisher, &

Vogel, 1965; D. Wilson, Reeves, Gazzaniga, & Culver, 1977). The procedure

has largely been abandoned by physicians, who are turning to less drastic surgeries

for even the most extreme cases of epilepsy (Woiciechowsky, Vogel, Meyer, &

Lehmann, 1997). Nonetheless, this medical procedure has produced a number of

“split-brain patients”; this provides an extraordi-nary research opportunity by

allowing us to examine how the brain halves function when they aren’t in full

communication with each other.

This research makes it clear that

each hemisphere has its own specialized capacities (Figure 3.31). For most

people, the left hemisphere has sophisticated language skills and is capable of

making sophisticated inferences. The right hemisphere, in contrast, has only

limited language skills; but it outperforms the left hemisphere in a variety of

spa-tial tasks such as recognizing faces and perceiving complex patterns (Gazzaniga,

Ivry, & Mangun, 2002; Kingstone, Freisen, & Gazzaniga, 2000).

These differences between the

left and right cerebral hemispheres are striking, but they’re clearly distinct

from many of the conceptions of hemispheric function written for the general

public. Some popular authors go so far as to equate left-hemisphere function

with Western science and right-hemisphere function with Eastern culture and

mysticism. In the same vein, others have argued that Western societies

overemphasize rational and analytic “left-brain” functions at the expense of

intuitive, artistic, “right-brain” functions.

These popular conceptions contain

a kernel of truth because, as we’ve seen, the two hemispheres are different in

several aspects of their functioning. But these often-mentioned conceptions go

far beyond the available evidence and are sometimes inconsistent with it

(Efron, 1990; J. Levy, 1985). Worse, these popular conceptions are entirely

misleading when they imply that the two cerebral hemi-spheres, each with its

own talents and strategies, endlessly compete for control of our mental life.

Instead, each of us has a single brain. Each part of the brain—not just the

cerebral hemispheres—is quite differentiated and so contributes its own

specialized abilities to the activity of the whole. But in the end, the

complex, sophis-ticated skills that we each display depend on the whole brain

and on the coordinated actions of all its components. Our hemispheres are not

cerebral competitors. Instead, they pool their specialized capacities to

produce a seamlessly integrated, single mental self.

Related Topics