Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease

Valvular Heart Disease: General Evaluation of Patients

Valvular Heart Disease

1. General Evaluation of Patients

Regardless of the lesion or its cause,

preoperative evaluation should be primarily concerned with determining the

identity and severity of the lesion and its hemodynamic significance, residual

ven-tricular function, and the presence of any secondary effects on pulmonary,

renal, and hepatic function.

Concomitant CAD should not be

overlooked, par-ticularly in older patients and those with known risk factors

(see above). Myocardial ischemia may also occur in the absence of significant

coronary occlusion in patients with severe aortic stenosis or regurgitation.

History

The preanesthesia history should focus

on symptoms related to decreased ventricular function. Symptoms and signs

should be correlated with laboratory data. Questions should evaluate exercise

tolerance, fatiga-bility, and pedal edema and shortness of breath in general

(dyspnea), when lying flat (orthopnea), or at night (paroxysmal nocturnal

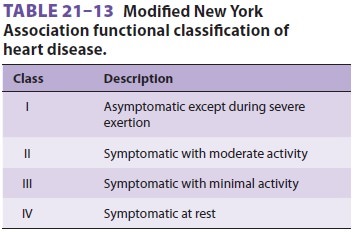

dyspnea). The New York Heart Association functional classification of heart

disease (Table

21–13) is useful for grading the severity of heart failure symptoms

and estimating prognosis. Patients should also be questioned about chest pains

and neurological symptoms. Some val-vular lesions are associated with thromboembolic

phenomena. Prior procedures, such as valvotomy or valve replacement and their

effects, should also be well documented.

A review of medications should evaluate

effi-cacy and exclude serious side effects. Commonly used agents include

diuretics, vasodilators, ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, antiarrhythmics, and

anti-coagulants. Preoperative vasodilator therapy may be used to decrease

preload, afterload, or both. Excessive vasodilatation worsens exercise

tolerance and is often first manifested as postural (orthostatic) hypotension.

Physical Examination

The most important signs to identify on

physical examination are those of congestive heart failure. Left-sided (S3 gallop or pulmonary rales) and right-sided (jugular

venous distention, hepatojugular reflux, hepatosplenomegaly, or pedal edema)

signs may be present. Auscultatory findings may confirm the valvular

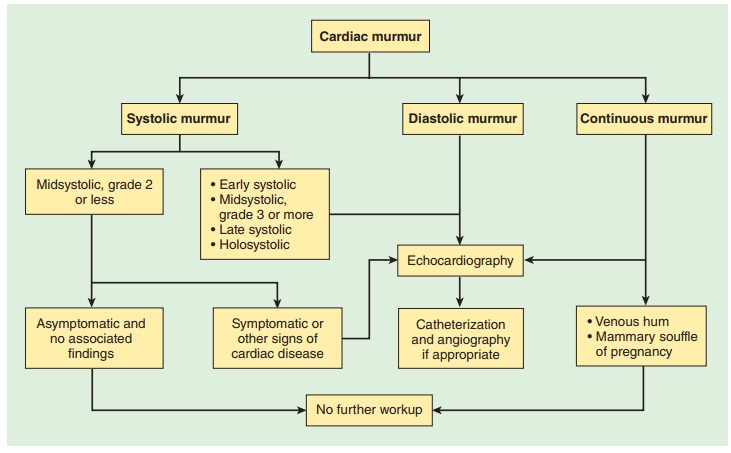

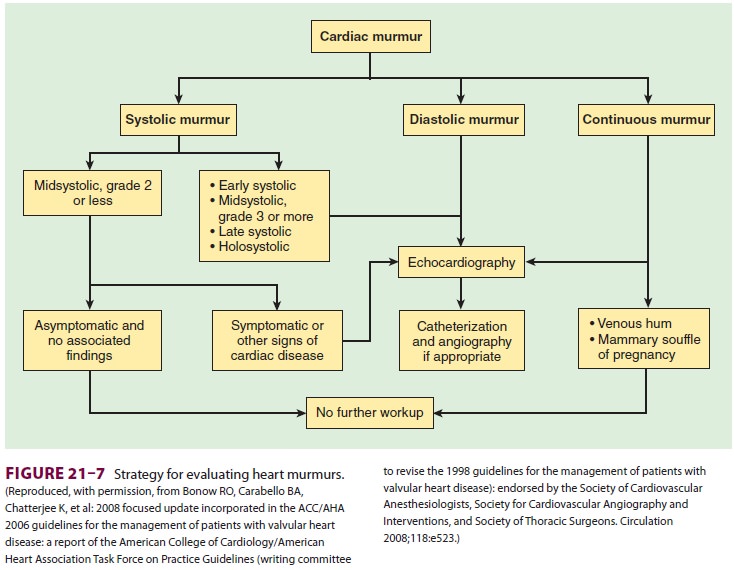

dysfunction ( Figure

21–7), but echocar-diographic studies are more reliable.

Neurological deficits, usually secondary to embolic phenomena, should be

documented.

Laboratory Evaluation

In addition to the laboratory studies

discussed for patients with hypertension and CAD, liver function tests may be

useful in assessing hepatic dysfunction caused by passive hepatic congestion in

patients with severe or chronic right-sided failure. Arterial blood gases can

be measured in patients with significant pulmonary symptoms. Reversal of

warfarin or hepa-rin should be documented with a prothrombin time and

international normalized ratio (INR) or partial thromboplastin time,

respectively, prior to surgery.

Electrocardiographic findings are

generally nonspecific. The chest radiograph is useful to assess cardiac size

and pulmonary vascular congestion.

Special Studies

Echocardiography, imaging studies, and

cardiac catheterization provide important diagnostic and prognostic information

about valvular lesions, but should only be obtained if the results will change

therapy or outcomes. More than one valvular lesion is often found. In many

instances, noninvasive stud-ies obviate the need for cardiac catheterization,

unless there are concerns about CAD. Information from these studies is best

reviewed with a cardiolo-gist. The following questions must be answered:

·

Which

valvular abnormality is most important hemodynamically?

·

What

is the severity of an identified lesion?

·

What

degree of ventricular impairment is present?

·

What

is the hemodynamic significance of other identified abnormalities?

· Is there any evidence of CAD?

The ACC/AHA have prepared detailed

guide-lines to assist in the management of the patient with valvular heart

disease. Although the evaluation of the patient with a heart murmur generally

rests with the cardiologist, anesthesia providers will on occa-sion discover

the presence of a previously undetected murmur on preanesthetic examination. In

particu-lar, anesthetists are concerned that undiagnosed, critical aortic

stenosis might be present, which could potentially lead to hemodynamic collapse

with either regional or general anesthesia. In the past, most val-vular heart

diseases were a consequence of rheumatic heart disease; however, with an aging

surgical popu-lation, increasing numbers of patients have degener-ative valve

problems. More than one in eight patients older than age 75 years may manifest

at least one form of moderate to severe valvular heart disease.

A study conducted in the Netherlands

reported that the prevalence of aortic stenosis was 2.4% in patients older than

age 60 years who were scheduled for elective surgery. Underdiagnosed valvular

disease is particularly prevalent in elderly females.

According to the ACC/AHA guidelines,

auscul-tation of the heart is the most widely used method to detect valvular

heart disease. Murmurs occur as a consequence of the accelerated blood flow

through narrowed openings in stenotic and regurgitant lesions. Although

systolic murmurs may be related to increased blood flow velocity, the ACC/AHA

guide-lines note that all diastolic and continuous murmurs reflect pathology.

Other than murmurs that are thought to be innocent, such as mid-systolic flow

murmurs (grade 2 or softer), the ACC/AHA guide-lines recommend

echocardiographic evaluation.

When new murmurs are detected in a

preoperative evaluation, consultation with the patient’s personal physician is

helpful to determine the need for echo-cardiographic evaluation. In many

centers, immedi-ate echocardiographic evaluation can be performed in the

preoperative area.

Related Topics