Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease

Hypertension: Intraoperative Management

INTRAOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Objectives

The overall anesthetic plan for a

hypertensive patient is to maintain an appropriate stable blood pressure range.

Patients with borderline hypertension may be treated as normotensive patients.

Those with long-standing or poorly controlled hypertension, how-ever, have

altered autoregulation of cerebral blood flow; higher than normal mean blood

pressures may be required to maintain adequate cerebral blood flow. Because

most patients with long-standing hypertension are assumed to have some element

of CAD and cardiac hypertrophy, excessive blood pressure elevations are

undesirable. Hypertension, particularly in association with tachycardia, can

precipitate or exacerbate myocardial ischemia, ventricular dysfunction, or

both. Arterial blood pressure should generally be kept within 20% of

preoperative levels. If marked hypertension (>180/ 120 mm Hg) is present preoperatively, arterial

blood pressure should be maintained in the high-normal range (150–140/90–80 mm

Hg).

Monitoring

Most hypertensive patients do not

require special intraoperative monitors. Direct intraarterial pres-sure

monitoring should be reserved for patients with wide swings in blood pressure

and those undergo-ing major surgical procedures associated with rapid or marked

changes in cardiac preload or afterload.

Electrocardiographic monitoring should

focus on detecting signs of ischemia. Urinary output should generally be

monitored with an indwelling urinary catheter in patients with a preexisting

renal impair-ment who are undergoing procedures expected to last more than 2

hr. When invasive hemodynamic monitoring is used, reduced ventricular

compli-ance is often apparent in

patients with ventricular hypertrophy; these patients may require more

intravenous fluid to produce a higher filling pressure to maintain adequate

left ventricular end-diastolic volume and cardiac output. Volume administration

in patients with decreased ventricu-lar compliance can also result in elevated

pulmonary arterial pressures and pulmonary congestion.

Induction

Induction of anesthesia and endotracheal

intubation are often associated with hemodynamic instability in hypertensive

patients. Regardless of the level of preoperative blood pressure control,

manypatients with hypertension display an accentuated hypotensive response to

induction of anesthesia, fol-lowed by an exaggerated hypertensive response to

intubation. Many, if not most, antihypertensive agents and general anesthetics

are vasodilators, cardiac depressants, or both. In addition, many hypertensive

patients present for surgery in a volume-depleted state. Sympatholytic agents

attenuate the normal pro-tective circulatory reflexes, reducing sympathetic

tone and enhancing vagal activity.

Up to 25% of hypertensive patients may

exhibit severe hypertension following endotracheal intuba-tion. Prolonged

laryngoscopy should be avoided. Moreover, intubation should generally be

performed under deep anesthesia (provided hypotension can be avoided). One of

several techniques may be used before intubation to attenuate the hypertensive

response:

·

Deepening

anesthesia with a potent volatile agent

·

Administering

a bolus of an opioid (fentanyl, 2.5–5 mcg/kg; alfentanil, 15–25 mcg/kg;

sufentanil, 0.5–1.0 mcg/kg; or remifentanil, 0.5–1 mcg/kg).

·

Administering

lidocaine, 1.5 mg/kg intravenously, intratracheally, or topically in the airway

·

Achieving

β-adrenergic blockade with esmolol, 0.3–1.5 mg/kg;

metoprolol 1–5 mg;or labetalol, 5–20 mg.

Choice of Anesthetic Agents

A. Induction Agents

The superiority of any one agent or

technique over another has not been established. Propofol, barbi-turates,

benzodiazepines, and etomidate are equally safe for inducing general anesthesia

in most hyper-tensive patients. Ketamine by itself can precipitate marked

hypertension; however, it is almost never used as a single agent. When

administered with a small dose of another agent, such as a benzodiaz-epine or

propofol, ketamine’s sympathetic stimulat-ing properties can be blunted or

eliminated.

B. Maintenance Agents

Anesthesia may be safely continued with

volatile agents (alone or with nitrous oxide), a balanced technique (opioid + nitrous oxide + muscle

relax-ant), or a total intravenous technique. Regardless of the primary

maintenance technique, addition of a volatile agent or intravenous vasodilator

gener-ally allows convenient intraoperative blood pressure control.

C. Muscle Relaxants

With the possible exception of large

bolus doses of pancuronium, any muscle relaxant can be used.

Pancuronium-induced vagal blockade and neu-ral release of catecholamines could

exacerbate hypertension in poorly controlled patients, but, if given slowly, in

small increments, pancuronium is unlikely to cause medically important increases

in heart rate or blood pressure. Moreover, pan-curonium can be useful in

offsetting excessive vagal tone induced by opioids or surgical manipulations.

Hypotension following large (intubating) doses of atracurium may be accentuated

in hypertensive patients.

D. Vasopressors

Hypertensive patients may display an

exagger-ated response to both endogenous catecholamines (from intubation or

surgical stimulation) and exogenously administered sympathetic agonists. If a

vasopressor is necessary to treat excessive hypotension, a small dose of a

direct-acting agent, such as phenylephrine (25–50 mcg), may be use-ful.

Patients taking sympatholytics preoperatively may exhibit a decreased response

to ephedrine. Vasopressin as a bolus or infusion can also be employed to

restore vascular tone in the hypoten-sive patient.

Intraoperative Hypertension

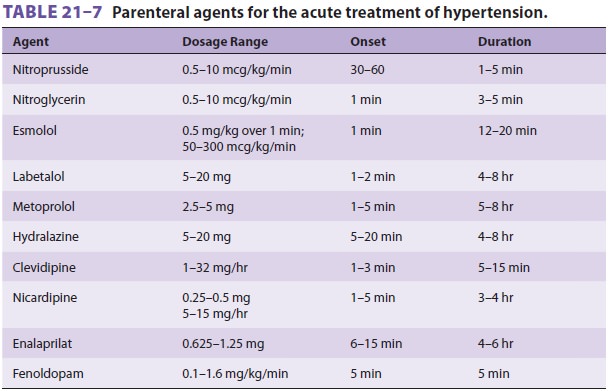

Intraoperative hypertension not

responding to an increase in anesthetic depth (particularly with a vol-atile

agent) can be treated with a variety of parenteral agents (Table 21–7). Readily reversible

causes— such as inadequate anesthetic depth, hypoxemia, or hypercapnia—should

always be excluded before initiating antihypertensive therapy. Selection of a

hypotensive agent depends on the severity, acute-ness, and cause of hypertension;

the baseline ven-tricular function; the heart rate; the presence of

bronchospastic pulmonary disease; and the anes-thetist’s familiarity with each

of the drug options. β-Adrenergic blockade alone or as a

supplement isa good choice for a patient with good ventricular function and an

elevated heart rate, but is relatively contraindicated in a patient with

bronchospastic disease. Metoprolol, esmolol, or labetolol are read-ily used

intraoperatively. Nicardipine or clevidipine may be preferable to β-blockers for

patients with bronchospastic disease. Nitroprusside remains the most rapid and

effective agent for the intraopera-tive treatment of moderate to severe

hypertension. Nitroglycerin may be less effective, but is also use-ful in

treating or preventing myocardial ischemia. Fenoldopam, a dopamine agonist, is

also a useful hypotensive agent; furthermore, it increases renal blood flow.

Hydralazine provides sustained blood pressure control, but also has a delayed

onset and can cause reflex tachycardia. The latter is not seen with labetalol

because of a combined α- and β-adrenergic blockade.

Related Topics