Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease

Aortic Stenosis

AORTIC STENOSIS

Preoperative Considerations

Valvular aortic stenosis is the most

common cause of obstruction to left ventricular outflow. Left ven-tricular

outflow obstruction is less commonly due to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,

discrete congenital subvalvular stenosis, or, rarely, supravalvular ste-nosis.

Valvular aortic stenosis is nearly always con-genital, rheumatic, or

degenerative. Abnormalities in the number of cusps (most commonly a bicuspid

valve) or their architecture produce turbulence that traumatizes the valve and

eventually leads to steno-sis. Rheumatic aortic stenosis is rarely isolated; it

is more commonly associated with aortic regurgita-tion or mitral valve disease.

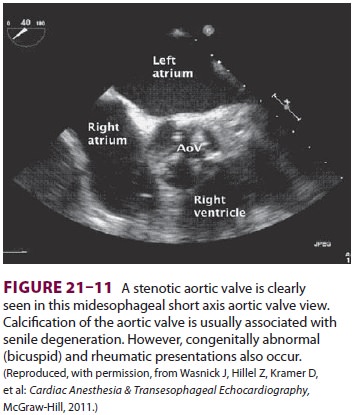

In the most common degenerative form, calcific aortic stenosis, wear and tear

results in the buildup of calcium deposits on normal cusps, preventing them

from opening com-pletely (Figure 21–11).

Pathophysiology

Left ventricular outflow obstruction caused

by val-vular aortic stenosis is almost always gradual, allow-ing the ventricle,

at least initially, to compensate and maintain SV. Concentric left ventricular

hypertrophy enables the ventricle to maintain SV by generating the needed

transvalvular pressure gradient and to reduce ventricular wall stress.

Critical aortic stenosis is said to

exist when the aortic valve orifice is reduced to 0.5–0.7 cm2 (normal is 2.5–3.5 cm2).

With this degree of stenosis, patients generally have a transvalvular gradient

of approxi-mately 50 mm Hg at rest (with a normal cardiac output) and are

unable to increase cardiac output in response to exertion. Moreover, further

increases in the transvalvular gradient do not significantly increase SV. With

long-standing aortic stenosis, myocardial contractility progressively

deteriorates and compromises left ventricular function.

Classically, patients with advanced

aortic ste-nosis have the triad of dyspnea on exertion, angina, and orthostatic

or exertional syncope. A promi-nent feature of aortic stenosis is a decrease in

left ventricular compliance as a result of hypertrophy. Diastolic dysfunction

is the result of an increase in ventricular muscle mass, fibrosis, or

myocardial ischemia. In contrast to left ventricular end-diastolic volume,

which remains normal until very late in the disease, left ventricular

end-diastolic pressure is elevated early in the disease. The decreased

dia-stolic pressure gradient between the left atrium and left ventricle impairs

ventricular filling, which becomes quite dependent on a normal atrial

con-traction. Loss of atrial systole can precipitate con-gestive heart failure

or hypotension in patients with aortic stenosis. Cardiac output may be normal

in symptomatic patients at rest, but characteristically, it does not

appropriately increase with exertion. Patients may experience angina even in

the absence of CAD. Myocardial oxygen demand increases because of ventricular

hypertrophy, whereas myo-cardial oxygen supply decreases as a result of the

marked compression of intramyocardial coronary vessels caused by high

intracavitary systolic pres-sures (up to 300 mm Hg). Exertional syncope or

near-syncope is thought to be due to an inability to tolerate the

vasodilatation in muscle tissue during exertion. Arrhythmias leading to severe

hypoper-fusion may also account for syncope and sudden death in some patients.

Related Topics