Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease

Heart Failure

HEART FAILURE

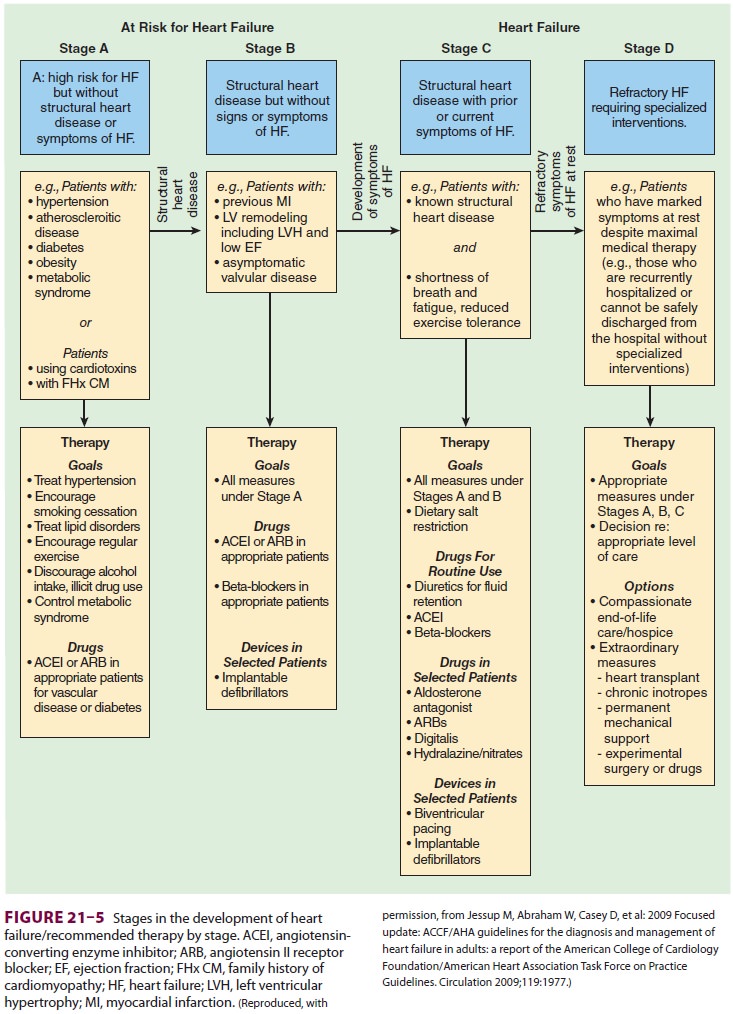

An increasing number of patients present

for sur-gery with either systolic and/or diastolic heart failure. Congestive

heart failure affects more than 5 million Americans. Heart failure may be

second-ary to ischemia, valvular heart disease, infectious agents, and many

types of cardiomyopathy. Most patients seek medical attention secondary to

heart failure because of complaints of dyspnea and fatigue. Heart failure develops

over time, as symptoms worsen (Figure 21–5). Patients generally undergo

echocardiography to diagnose structural heart defects, to detect signs of

cardiac “remodeling”, to determine the left ventricular ejection fraction, and

to assess the heart’s diastolic function. Laboratory evaluations of

concentration of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) are likewise obtained to

distinguish heart failure from other causes of dyspnea. BNP is released from

the heart, and its elevation is associ-ated with impaired ventricular

function.In response to ventricular failure, the body attempts to compensate

for LV systolic function through the sympathetic and renin–angiotensin–

aldosterone system. Consequently, patients experi-ence salt retention, volume

expansion, sympathetic stimulation, and vasoconstriction. The heart dilates to

maintain the stroke volume in spite of decreased contractility. Over time,

compensatory mecha-nisms fail and contribute to the symptoms asso-ciated with

heart failure (eg, edema, tachycardia, decreased tissue perfusion). Patients

with systolic heart failure are likely to present to surgery hav-ing been

previously treated with diuretics, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor

blockers, and

possibly aldosterone antagonists.

Electrolytes must be measured, as heart failure therapies frequently lead to

changes in serum potassium concentration. Angiotensin receptor blocker or ACE

inhibitor use may contribute to periinduction hypotension in the patient with

heart failure. ACE inhibitors are rarely associated with angioedema requiring

emergent airway management.

Diastolic ventricular dysfunction

pro-duces symptoms of congestion and heart failure. Myocardial relaxation is a

dynamic, not passive, process. The heart with preserved diastolic func-tion

accommodates volume during diastole, with minimal increases in left ventricular

end-diastolic pressure. Conversely, the heart with diastolic dys-function

relaxes poorly and produces increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure.

The left ven-tricular end-diastolic pressure is transmitted to the left atrium

and pulmonary vasculature resulting in symptoms of congestion.

Anesthetic management of the patient

with heart failure requires careful assessment and opti-mization of

intravascular fluid volume—especially if positive inotropic agents,

vasoconstrictors, or vasodilators are used. In particular, patients with

diastolic dysfunction may tolerate increases in volume poorly, leading to

pulmonary congestion.

Related Topics