Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease

Hypertension:Preoperative Management

PREOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

A recurring question in anesthetic

practice is the degree of preoperative hypertension that is accept-able for

patients scheduled for elective surgery. Except for optimally controlled

patients, most hyper-tensive patients present to the operating room with some

degree of hypertension. Although data suggest that even moderate preoperative

hypertension (dia-stolic pressure <90–110 mm Hg) is not clearly

statis-tically associated with postoperative

complications, other data indicate that the untreated or poorly con-trolled

hypertensive patient is more apt to experi-ence intraoperative episodes of myocardial ischemia, arrhythmias, or

both hypertension and hypotension. Intraoperative adjustments in anesthetic

depth and use of vasoactive drugs should reduce the incidence of postoperative

complications referable to poor preoperative control of hypertension.

Although patients should ideally undergo elective surgery only when rendered normoten-sive, this is not always feasible or necessarily desir-able because of altered cerebral autoregulation. Excessive reductions in blood pressure can com-promise cerebral perfusion. Moreover, the deci-sion to delay or to proceed with surgery should be individualized, based on the severity of the preop-erative blood pressure elevation; the likelihood of coexisting myocardial ischemia, ventricular dys-function, or cerebrovascular or renal complica-tions; and the surgical procedure (whether major surgically induced changes in cardiac preload or afterload are anticipated). With rare exceptions, antihypertensive drug therapy should be con-tinued up to the time of surgery. Some clinicians withhold ACE inhibitors and ARBs on the morn-ing of surgery because of their association with an increased incidence of intraoperative hypoten-sion; however, withholding these agents increases the risk of marked perioperative hypertension and the need for parenteral antihypertensive agents. It also requires the surgical team to remember torestart the medication after surgery. The decision to delay elective surgical procedures in patients with sustained preoperative diastolic blood pressures higher than 110 mm Hg should be made when the perceived benefits of delayed surgery exceed the risks. Unfortunately, there are few appropriate studies to guide the decision-making.

History

The preoperative history should inquire

into the severity and duration of the hypertension, the

drug therapy currently prescribed, and

the pres-ence or absence of hypertensive complications. Symptoms of myocardial

ischemia, ventricular failure, impaired cerebral perfusion, or peripheral

vascular disease should be elicited, as well as the patient’s record of

compliance with the drug regi-men. The patient should be questioned regarding

chest pain, exercise tolerance, shortness of breath (particularly at night),

dependent edema, postural lightheadedness, syncope, episodic visual

dis-turbances or episodic neurologic symptoms, and claudication. Adverse

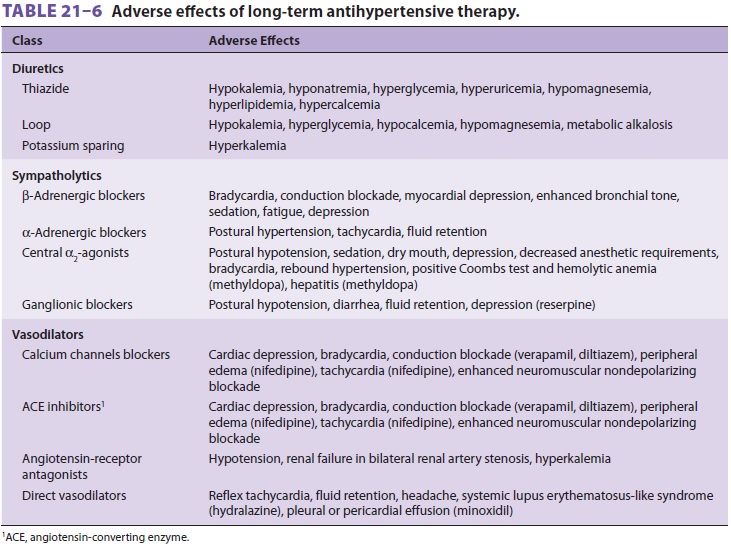

effects of current antihyper-tensive drug therapy (Table 21–6) should also be

identified.

Physical Examination & Laboratory Evaluation

Ophthalmoscopy is useful in hypertensive patients. Visible changes in the retinal vasculature usually parallel the severity and progression of arterioscle-rosis and hypertensive damage in other organs. An S4 cardiac gallop is common in patients with LVH. Other physical findings, such as pulmonary rales and an S 3 cardiac gallop, are late findings and indi-cate congestive heart failure. Blood pressure can be measured in both the supine and standing positions. Orthostatic changes can be due to volume deple-tion, excessive vasodilatation, or sympatholytic drug therapy; preoperative fluid administration can pre-vent severe hypotension after induction of anesthe-sia in these patients. Although asymptomatic carotid bruits are usually hemodynamically insignificant, they may be reflective of atherosclerotic vascular disease that may affect the coronary circulation. When a bruit is detected, further workup should be guided by the urgency of the scheduled surgery and the likelihood that further investigations, if diag-nostic, would result in a change in therapy. Doppler studies of the carotid arteries can be used to define the extent of carotid disease.

The ECG is often normal, but in patients

with a long history of hypertension, it may show evi-dence of ischemia,

conduction abnormalities, an old infarction, or LVH or strain. A normal ECG

does not exclude CAD or LVH. Similarly, a normal heart size on a chest

radiograph does not exclude ventricular hypertrophy. Echocardiography is a

sensitive test of LVH and can be used to evaluate ventricular systolic and

diastolic functions in patients with symptoms of heart failure. Chest

radiographs are rarely useful in an asymptomatic patient, but may show a

boot-shaped heart (suggestive of LVH), frank cardiomeg-aly, or pulmonary

vascular congestion.

Renal function is best evaluated by

measure-ment of serum creatinine and blood urea nitro-gen levels. Serum

electrolyte levels (K) should be determined in patients taking diuretics or

digoxin or those with renal impairment. Mild to moder-ate hypokalemia (3–3.5

mEq/L) is often seen in patients taking diuretics, but does not have adverse

outcome effects. Potassium replacement should be undertaken only in patients

who are symptomatic or who are also taking digoxin. Hypomagnesemia is often

present and may be a cause of perioperative arrhythmias. Hyperkalemia may be

encountered in patients who are taking potassium-sparing diuretics or ACE

inhibitors, particularly those with impaired renal function.

Premedication

Premedication reduces preoperative

anxiety and is desirable in hypertensive patients. Mild to moderate

preoperative hypertension often resolves following administration of an agent

such as midazolam.

Related Topics