Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease

Hypertension

HYPERTENSION

Patients with hypertension frequently

present for elective surgical procedures. Some will have been effectively

managed, but unfortunately, many others will not have been. Hypertension is a

leading cause of death and disability in most Western societies and the most

prevalent preoperative medical abnormal-ity in surgical patients, with an

overall prevalence of 20% to 25%. Long-standing uncontrolled hyper-tension

accelerates atherosclerosis and hypertensive organ damage. Hypertension is a

major risk factor for cardiac, cerebral, renal, and vascular disease.

Complications of hypertension include

MI, con-gestive heart failure, stroke, renal failure, periph-eral occlusive

disease, and aortic dissection. The presence of left ventricular hypertrophy

(LVH) in hypertensive patients may be an important predic-tor of cardiac

mortality. However, systolic blood pressures below 180 mm Hg, and diastolic

pressures below 110 mm Hg, have not been associated with increased

perioperative risks. When patients present with systolic blood pressures

greater than 180 mm Hg and diastolic pressures greater than 110 mm Hg,

anesthesiologists face the dilemma of delaying sur-gery to allow optimization

of oral antihypertensive therapy, but adding the risk of a surgical delay

versus proceeding with surgery and achieving blood pres-sure control with

rapidly acting intravenous agents. Intravenous β-blockers can be useful to treat

preop-erative hypertension. Of note, patients with preop-erative hypertension

are more likely than others to develop intraoperative hypotension. This is

particu-larly frequent in patients treated with angiotensin receptor blockers

and/or angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

Blood pressure measurements are affected

by many variables, including posture, time of day or night, emotional state,

recent activity, and drug intake, as well as the equipment and technique used.

A diagnosis of hypertension cannot be made by one preoperative reading, but

requires confirmation by a history of consistently elevated measurements.

Although preoperative anxiety or pain may produce some degree of hypertension

in normal patients, patients with a history of hypertension generally exhibit

greater preoperative elevations in blood pressure.

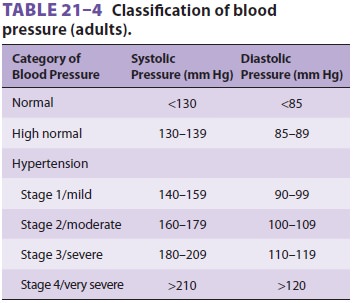

Epidemiological studies demonstrate a

direct and continuous correlation between both diastolic and systolic blood

pressures and mortality rates. The definition of systemic hypertension is

arbitrary: a consistently elevated diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mm

Hg or a systolic pressure greater than 140 mm Hg. A common classification

scheme is listed in Table 21–4. Borderline hypertension is said to

exist when the diastolic pressure is 85–89 mm Hg or the systolic pressure is

130–139 mm Hg. Whether patients with borderline hypertension are at some

increased risk for cardiovascular complications remains unclear. Accelerated,

or severe hypertension (stage 3), is defined as a recent, sustained, and

pro-gressive increase in blood pressure, usually with dia-stolic blood

pressures in excess of 110–119 mm Hg. Renal dysfunction is often present in

such patients. Malignant hypertension is a true medical emer-gency

characterized by severe hypertension (>210/ 120 mm Hg) often associated with

papilledema and encephalopathy.

Pathophysiology

Hypertension can be either idiopathic

(essential), or, less commonly, secondary to other medical con-ditions such as

renal disease, renal artery stenosis, primary hyperaldosteronism, Cushing’s

disease, acromegaly, pheochromocytoma, pregnancy, or estrogen therapy.

Essential hypertension accountsfor 80% to 95% of cases and may be associated

with an abnormal baseline elevation of cardiac output, systemic vascular

resistance (SVR), or both. An evolving pattern is commonly seen over the course

of the disease, where cardiac output returns to (or remains) normal, but SVR

becomes abnormally high. The chronic increase in cardiac afterload results in

concentric LVH and altered diastolic function. Hypertension also alters

cerebral autoregulation, such that normal cerebral blood flow is maintained in

the face of high blood pressures; autoregulation limits may be in the range of

mean blood pressures of 110–180 mm Hg.

The mechanisms responsible for the

changes observed in hypertensive patients seem to involve vascular hypertrophy,

hyperinsulinemia, abnormal increases in intracellular calcium, and increased

intracellular sodium concentrations in vascu-lar smooth muscle and renal

tubular cells. The increased intracellular calcium presumably results in

increased arteriolar tone, whereas the increased sodium concentration impairs

renal excretion of sodium. Sympathetic nervous system overactivity and enhanced

responses to sympathetic agonists are present in some patients. Hypertensive

patients sometimes display an exaggerated response to vasopressors and

vasodilators. Overactivity of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system seems to

play an important role in patients with accelerated hypertension.

Long-Term Treatment

Effective drug therapy reduces the

progression of hypertension and the incidence of stroke, conges-tive heart

failure, CAD, and renal damage. Effective treatment can also delay and

sometimes reverse con-comitant pathophysiological changes, such as LVH and

altered cerebral autoregulation.

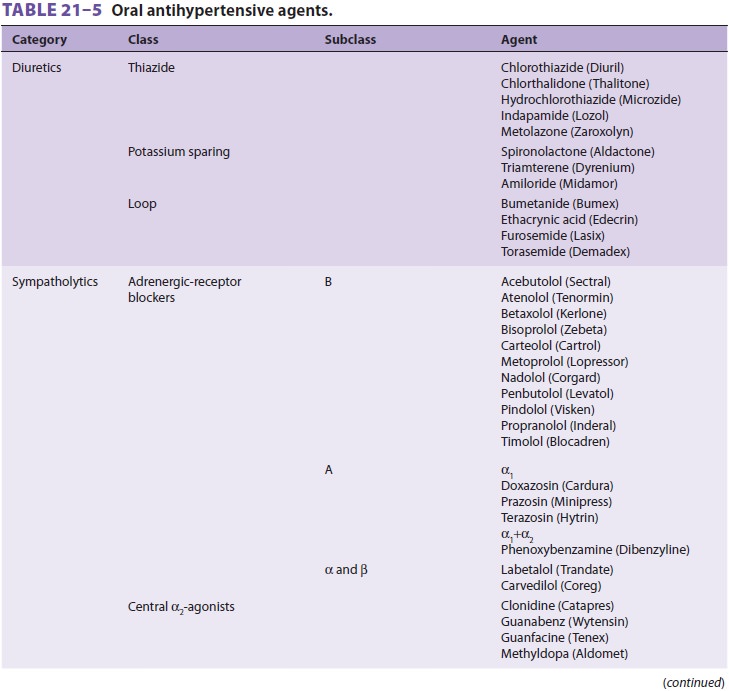

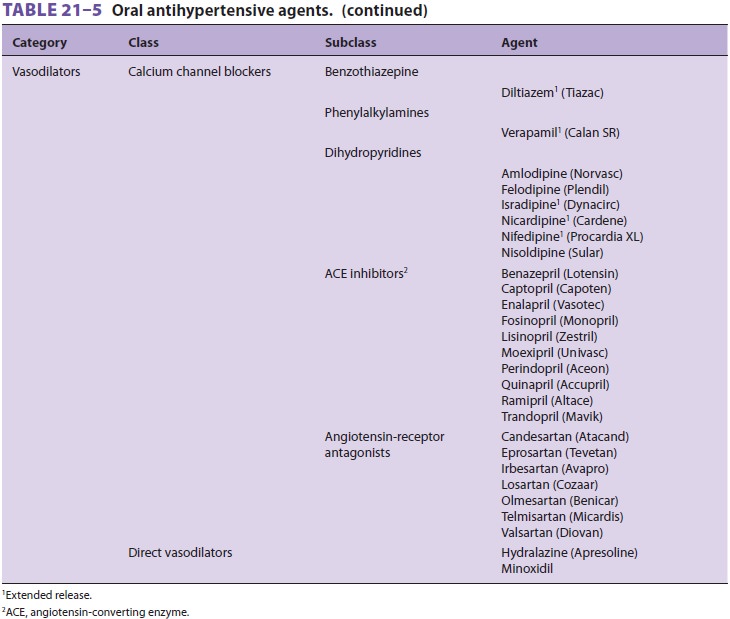

Some patients with mild hypertension

require only single-drug therapy, which may consist of a thi-azide diuretic,

ACE inhibitor, angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB), β-adrenergic blocker, or calcium channel

blocker, although guidelines and outcome studies favor the first three options.

Concomitant illnesses should guide drug selection. All patients with a prior MI

should receive a β-adrenergic blocker and an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) to

improve outcomes, irrespective of the presence of hyperten-sion. In many

patients, the “guideline specified” agents will also be more than sufficient to

control hypertension.

Patients with moderate to severe

hyperten-sion often require two or three drugs for control. The combination of

a diuretic with a β-adrenergic blocker and an ACE inhibitor is often

effective when single-drug therapy is not. As previously noted, ACE inhibitors

(or ARBs) prolong survival in patients with congestive heart failure, left

ventricular dys-function, or a prior MI. Familiarity with the names, mechanisms

of action, and side effects of commonly used antihypertensive agents is

important for anes-thesiologists (Table 21–5).

Related Topics