Chapter: Psychology: Psychopathology

The Roots of Mood Disorders

The Roots of Mood Disorders

What

produces the mood disorders? Depression and bipolar disorder are thought to

result from multiple contributing factors, factors that include genetic,

neurochemical, and psychological influences.

GENETIC FACTORS

The

mood disorders have important genetic components. This is reflected in the fact

that the concordance rate is roughly two times higher in identical twins than

in frater-nal twins (Sullivan, Neale, & Kendler, 2000). The pattern is even

clearer for bipolar dis-order: If someone’s identical twin has the disorder,

there is a 60% chance that he, too, will have the disorder; the concordance

rate for fraternal twins is much lower, 12% (Kelsoe, 1997).

Adoption

studies point to the same conclusion, and the biological relatives of adopted

children with depression are themselves at high risk for depression (Wender,

Kety, Rosenthal, Schulsinger, & Ortmann, 1986). Likewise, the risk of

suicide is much higher among the biological relatives of depressed adoptees

than it is in the biological kin of nondepressed adoptees (Wallace, Schneider,

& McGuffin, 2002).

Importantly,

though, the genetic evidence indicates a clear distinction between depression

and bipolar disorder. The two disorders overlap in their symptoms (i.e.,

clinical depression resembles the depressed phase of bipolar disorder), but

they proba-bly arise from different sources. This is evident, for example, in

the fact that people with one of these disorders tend to have relatives with

the same condition but not the other. Apparently, then, there are separate

inheritance pathways for each, making it likely that they are largely separate

disorders (Gershon, Nurnberger, Berrettini, & Goldin 1985; Moffitt, Caspi,

& Rutter, 2006; Torgersen, 1986; Wender et al., 1986).

BRAIN BASES

Drugs

that influence the effects of various neurotransmitters can often relieve

symp-toms of mood disorders, and this suggests that these mood disorders arose

in the first place because of a disorder in neurotransmission. Three

neurotransmitters seem criti-cal for mood disorders: norepinephrine, dopamine,

and serotonin. Many of the anti-depressant and mood-stabilizing medications

work by altering the availability of these chemicals at the synapse (Miklowitz

& Johnson, 2006; Schildkraut, 1965).

How

these neurochemical abnormalities lead to mood disorders is uncertain, but it

is clear that these disorders involve more than a simple neurotransmitter

shortage or excess. In the case of depression, this is evident in the fact that

antidepressant drugs work almost immediately to increase the availability of

neurotransmitters, but their clinical effects usually do not appear until a few

weeks later. Thus, neurotransmitter problems are involved in depression (otherwise

the drugs would not work at all), but the exact nature of those problems

remains unclear.

In

the case of bipolar disorder, the mystery lies in the cycling between manic and

depressive episodes, especially since, in some patients, this cycling is quite

rapid and seemingly divorced from external circumstances. Some believe the

cycling is related to dysfunction in neuronal membranes, with the consequence

that the membranes mismanage fluctuations in the levels of various

neurotransmitters (Hirschfeld & Goodwin, 1988; Meltzer, 1986).

To

better understand the underlying brain bases of these mood disorders,

researchers have used both structural and functional brain imaging. Studies

using positron emission tomography (PET) show that severe depression is associated

with heightened brain acti-vation in a limbic system region known as the

subgenual cingulate cortex (Drevets, 1998). This finding makes sense, given

that inducing sadness in healthy participants leads to increased activation in

this brain region (Mayberg et al., 1999), as well as the evi-dence that when

depression is successfully treated, brain activity in this region returns to

normal levels (Mayberg et al., 1997).

In

the case of bipolar disorder, imaging studies suggest that adults with bipolar

dis-order have greater amygdala volumes than age-matched healthy controls

(Brambrilla et al., 2003). Functional-imaging studies parallel these structural

studies, showing greater brain activity in subcortical emotion-generative brain

regions such as the amyg-dala (Phillips, Ladouceur, & Drevets, 2008).

PSYCHOLOGICALRISKFACTORS

Our

account of the mood disorders also needs to take account of life experiences.

For example, depression and bipolar disorder are often precipitated by an

identifiable life crisis, whether that crisis involves marital or professional

difficulties, serious physical illness, or a death in the family (S. L.

Johnson, 2005a; Monroe & Hadjiyannakis, 2002; Neria et al., 2008). Broader

contextual factors, such as whether someone lives in a good or bad

neighborhood, may also influence whether a person develops depression, even

when controlling for risk factors associated with the person’s age, ethnicity,

income, education, and employment status (Cutrona, Wallace, & Wesner,

2006). The impor-tance of psychological factors is also evident in the fact

that individuals with mood dis-orders are at much greater risk for relapse if

they return after hospitalization to families who show high levels of criticism

and hostility (Hooley, Gruber, Scott, Hiller, & Yurgelin-Todd, 2005;

Miklowitz, 2007; Segal, Pearson, & Thase, 2003).

As

we mentioned earlier, though, personal and environmental stresses do not, by

themselves, cause mood disorders. What we need to ask is why some people are

unable to bounce back after a hard blow and why, instead of recovering, they

spiral downward into depression.

Part

of the explanation may be genetic, and some researchers are focusing on a gene

that regulates how much serotonin is available at the synapse. As discussed,

the gene itself is not the source of depression; instead, the gene seems to

create a vulner-ability to depression. The illness itself will emerge only if

the vulnerable person also experiences some significant life stress (Caspi et

al., 2003). However, this finding has been controversial, and research in this

area is ongoing (e.g., Munafo, Durrant, Lewis, & Flint, 2009; Risch et al.,

2009).

Another

part of the explanation for why stress puts some people at greater risk for

depression than others turns out to be social: severe stress is less likely to

lead to a mood disorder if a person has supportive family and friends (Brown

& Harris, 1978; Johnson et al., 1999; Joiner, 1997). Still another crucial

factor is how a person thinks about stressful events when they occur.

Many

depressed individuals—whether they are experiencing unipolar depression or are

in the depressive phase of bipolar disorder—believe that both they and the

world are hopeless and wretched. It seems plausible that these beliefs are

produced by the patient’s mood, but, according to the psychiatrist Aaron Beck,

the opposite is true, at least in the case of depression: The beliefs come

first; they produce the depression (see, for example, Beck, 1967, 1976). Beck

argues that depression stems from a set of intensely negative and irrational

beliefs: the beliefs some people hold that they are worthless, that their

future is bleak, and that whatever happens around them is sure to turn out for

the worst. These beliefs form the core of a negative cognitive schema by which a person interprets whatever

happens to her, leaving her mood nowhere to go but down.

A

related account of depression also focuses on how people think about what

happens to them. As we saw, people differ in how they explain bad events. Do we

think that a bad event happened because of something we did, so that, in some

direct way, we caused the event? Do we believe that similar bad events will

arise in other aspects of our lives? And do we think that bad events will

continue to happen to us, perhaps for the rest of our lives? Peterson and

Seligman propose that much depends on how we answer these questions, and,

moreover, they suggest that each of us has a consistent style for how we tend

to answer such questions—which they call an explanatory style. In their view, a person is vulnerable to

depression if her explanatorystyle tends to be internal (“I, and not some

external factor, caused the event”), global (“This sort of event will also

happen in other areas of my life”), and stable (“This is going to keep

happening”). This explanatory style is not by itself the source of depres-sion;

once again, we need to separate diathesis and stress. But if someone has this

explanatory style and then experiences a bad event, that person is at

considerably elevated risk for depression (Peterson & Seligman, 1984). In

addition, it appears that the explanatory style usually predates the

depression, with the clear implication that this way of interpreting the world

is not caused by depression but is instead a factor predisposing an individual

toward depression (Abramson et al., 2002; Alloy, Abramson, & Francis, 1999;

Peterson & Park, 2007).

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RISK FACTORS

Clearly,

there are both biochemical and cognitive contributors to mood disorders. As we mentioned

earlier, though, mood disorders are also influenced by social settings. This is

evident, for example, in the fact that depression is less likely among people

with a strong social netowork of friends or family. The importance of social

surroundings is also visible in another way: the role of culture in shaping the

likelihood that depression will emerge, or the form that the disorder takes.

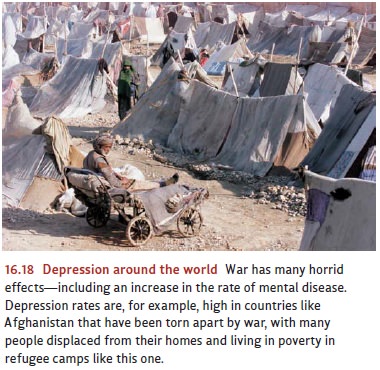

Depression

occurs in all cultures, and, in fact, the World Health Organization ranked

depression fourth among all causes of disability worldwide (Miller, 2006b).

However, its prevalence varies widely from one country to the next. For

example, depression is—not surprisingly— more common in countries such as

Afghanistan that

have

been torn apart by war (Bolton & Betancourt, 2004; Figure 16.18); the

difficulties in such countries also lead to other disorders, including

post-traumatic stress disorder. In contrast, depression is much less commonly

diagnosed in China, Taiwan, and Japan than in the West. When the disorder is

detected in these Asian countries, the symptoms are less often psychological

(such as sadness or apathy) and more often bodily (such as sleep dis-turbance,

weight loss, or, in China, heart pain; Kleinman, 1986; G. Miller, 2006a; Tsai

& Chentsova-Dutton, 2002). Why is this? There are several possibilities,

starting with the fact that cultures differ in their display rules for emotion , which will obvi-ously influence the

presentation and diagnosis of almost any mental disorder. In addition, people

in these Asian countries may differ in how they understand and perhaps even

expe-rience their own symptoms, and this, too, can influence diagnosis.

Even

within a single country, the risk of mood disorders varies. Depression, for

example, is more common among lower socioeconomic groups (Dohrenwend, 2000;

Monroe & Hadjiyannakis, 2002), perhaps because these groups are exposed to

more stress. In contrast, bipolar disorder is more common among higher socioeconomic groups (Goodwin

& Jamison, 1990), conceivably because the behaviors produced during a

person’s hypomanic phases may lead to increased accomplishment.

Related Topics