Chapter: Psychology: Psychopathology

Assessing Mental Disorders

Assessing Mental Disorders

In

addition to this general definition of mental disorder, the DSM gives definitions of the specific

mental disorders, definitions that we can use to decide which disorder—if any—a

person has. These “definitions” consist of lists of specific criteria, a certain

number of which must be met for a given disorder to be diagnosed. The diagnosis

is important because it is the first step both in understanding why a person is

suffering and (crucially!) in deciding how to help that person.

Mental

health professionals use the term assessment

to refer to the set of proce-dures for gathering information about an

individual, and an assessment may or may not lead to a diagnosis—a claim that

an individual has a specific mental disorder. Clinical assessment often

includes clinical interviews, self-report measures, and pro-jective tests. It

may also include laboratory tests such as neuroimaging or blood analyses that can inform the

practitioner about the patient’s physical well-being—for example, whether the

patient has suffered a stroke or taken a mood-alter-ing drug.

CLINICAL INTERVIEWS

Assessments

usually begin with a clinical interview, in which the clinician asks the

patient to describe her problems and concerns (Figure 16.5). Some aspects of

the inter-view will be open-ended and flexible, as the clinician explores the

patient’s current state and history. In addition, the clinician may rely on a semistructured interview, in which

specific questions are asked in a specific sequence, with attention to certain

types of content. For example, the clinician might use the Structured Clinical

Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID), which is designed to ask questions directly

pertinent to certain diagnostic categories.

Throughout,

the clinician will pay careful attention to the patient’s set of com-plaints,

or symptoms. Patients who say, “I

hear voices,” “I feel nervous all the time,” and “I feel hopeless” are

reporting symptoms. The clinician also looks for any objective signs that might accompany these

symptoms. If the same patients, respectively, turntoward a stapler as though it

were speaking, shake visibly, and look teary-eyed, these would be signs that

parallel the patients’ symptoms. Sometimes, though, symptoms do not correspond

to signs, and such discrepancies are also important. For example, a patient

might state, “My head hurts so bad it’s like there’s a buzz saw running through

my brain,” even thought the patient seems to be calm and unconcerned, and this

discrepancy, too, is informative.

The

full pattern of the patient’s symptoms and signs, taken together with their

onset and course, will usually allow the clinician to form an opinion as to the

specific disorder(s). This diagnosis is not set in stone, but serves as the

practitioner’s best judgment about the patient’s current state. The diagnosis

may well be revised as the clinician gains new information, including

information about how the patient responds to a particular form of treatment.

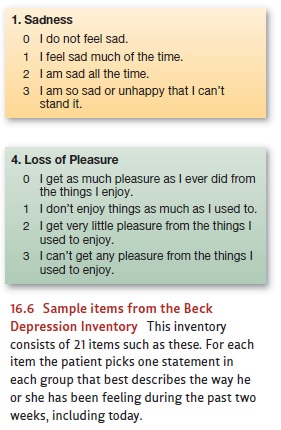

SELF –

REPORT MEASURES

In

some clinical assessments, a clinician will also seek information about a

patient by administering self-report measures. Some of these measures are

relatively brief and target a certain set of symptoms. These include measures

such as the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996); sample

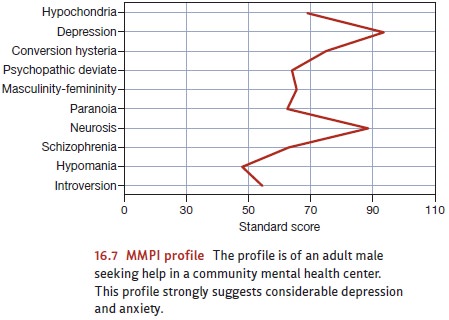

items from this inventory are shown in Figure 16.6. Other self-report measures

are much broader (and longer), such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality

Inventory, or MMPI. This test was developed in 1940 and was redesigned in 1989;

the current version, the MMPI-2, includes an imposing 567 items (Butcher,

Dahlstrom, Graham, Tellegen, & Kaemmer, 2001; Butcher et al., 1992).

To

construct the MMPI, its authors began with a large pool of test questions and

administered them to patients known to have a variety of different mental

disorders, as well as to a group of nonpatients. Next, they compared the

patients’ responses to those of the nonpatients. If all groups tended to

respond to a particular question in the same way, that question was deemed

uninformative and was removed from the test. A question was kept on the test

only if one of the patient groups tended to answer it differently from how the

nonpatient group answered it. The result was a test specifically

designed

to differentiate among patients with different mental disorders. Figure 16.7

shows an MMPI score profile.

PROJECTIVE TESTS

Some

clinicians supplement clinical interviews with what is called a projective

test. Advocates of projective tests argue that when the patient is asked to

respond to stimuli that are essentially unstructured or ambiguous, he cannot

help but impose a structure of his own, and, in the process of describing (or

relying on) this structure, he gives valuable information about unconscious

wishes and conflicts that could not be revealed by direct testing.

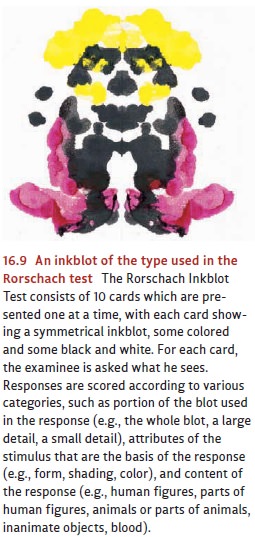

One

such test has the participant make up a story to describe what is going on in a

picture (the Thematic Apperception Test, or TAT; C. D. Morgan & Murray,

1935). Responses to these pictures are seen as revealing implicit or otherwise

hidden motives (Figure 16.8; McAdams, 1980; for variants on this procedure, see

McClelland, Koestner, & Weinberger, 1989; Winter, 1999). Another projective

test, the Rorschach Inkblot Test, has the patient describe what he sees in an

inkblot (Figure 16.9; Rorschach, 1921).

Projective

tests such as these are extremely popular—with more than 8 in 10 clini-cians

reporting that they use them at least occasionally (Watkins, Campbell,

Nieberding, & Hallmark, 1995). However, there is general agreement in the

research community that these tests’ popularity outstrips their demonstrated

validity. One review of Rorschach findings reported only small correlations

with mental health–related criteria (Garb, Florio, & Grove, 1998), and

there is ongoing debate about the role projective tests should play in diagnosis

(Garb, Wood, Nezworski, Grove, & Stejskal, 2001; Lilienfeld, Wood, &

Garb, 2000; Rosenthal, Hiller, Bornstein, Berry, & Brunell-Neuleib, 2001;

Westen & Weinberger, 2005).

Related Topics