Chapter: Psychology: Psychopathology

Conceptions of Mental Disorders

CONCEPTIONS OF

MENTAL

DISORDERS

We

have seen that people differ from one another in many ways, both in their

desirable qualities, like being intelligent or helpful, and in their

undesirable ones, like being selfish or aggressive. Even so, the attributes we

have considered all fall within the range that most people consider acceptable

or normal. In this, we consider differences that are outside the normal range

of variation— differences that carry us into the realm of mental disorders such

as depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia. These are conditions that cause

considerable suffer-ing and profoundly disrupt people’s lives—both the lives of

the people afflicted with the disorders and, often, the lives of others around

them.

The

study of mental disorders is the province of psychopathology, or, as it is sometimes called, abnormal

psychology. Like many corners of psychology, this domain has been studied

scientifically only in the last century. Concerns about mental illness,

however, have a much longer history. One of the earliest-known medical

documents, the Ebers papyrus (written about 1550 C.E.), refers to the disorder

we now know as depression (Okasha & Okasha, 2000). Other ancient cases

include King Saul of Judaea, who alternated between bouts of homicidal frenzy

and suicidal depression, and the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, who walked on

all fours in the belief that he was a wolf (Figure 16.1). Across the millennia,

though, people have had very different concep-tions of what causes these

disorders.

Early Conceptions of Mental Disorders

The

earliest theories held that a person afflicted by a mental disorder was

possessed by evil spirits. As we will see, people tried various extreme

remedies to deal with this problem, such as flogging and starving, with the aim

of driving the evil spirits away.

In

recent centuries, a more sophisticated conception of mental disorders began to

develop—namely, that they are a type of disease, to be understood in the same

way as other illnesses. Proponents of this somatogenic

hypothesis (from the Greek soma,

meaning “body”) argued that mental disorders, like other forms of illness,could

be traced to an injury or infection. This position gained considerable

credibil-ity in the late nineteenth century, thanks to discoveries about general paresis.

General

paresis is a disorder characterized by a broad decline in physical and

psy-chological functions, culminating in marked personality aberrations that

may include grandiose delusions (“I am the king of England”) or profound

hypochondriacal depressions (“My heart has stopped beating”). Without

treatment, the deterioration progresses to the point of paralysis, and death

occurs within a few years. The break-through in understanding paresis came in

1897, when the Viennese physician Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1840–1902)

discovered that it was actually a consequence of infec-tion with syphilis. This

discovery paved the way for the development of antibiotics that could cure the

infection, and, if the drugs were given early enough, the symptoms of paresis

could be avoided altogether.

It

seems, then, that general paresis can be understood and treated like any other

medical problem. Should other forms of mental disorder be understood in the

same fashion—as the result of an infection or perhaps an injury? This view

gained many supporters in the late 1800s, including Emil Kraepelin (Figure

16.2), whose textbook, Lehrbuch der

Psychiatrie, emphasized the importance of brain pathology in

producingmental disorders.

However,

a somatogenic approach cannot explain all mental disorders. For example, more

than a hundred years ago, scholars realized that this approach was not

appropriate for the disorder then known as hysteria, which we encountered in

our discussion of psychoanalysis . Patients with hysteria typically showed odd

symptoms that seemed to be neurological, but with other indications that made

it plain there was no neurological damage. Some patients reported that their

limbs were paralyzed, but under hypnosis they could move their arms and legs

perfectly well, indicating that the nerves and muscles were fully functional.

Their symptoms, therefore, were not the result of a bodily injury; instead,

they had to be understood in terms of a psychogenic

hypothesis, which holds that the symptoms arise via psychological

processes.

Across

much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the most prominent version of

this hypothesis was Sigmund Freud’s, which described mental illness as

resulting from inner conflicts and defensive maneuvers aimed at dealing with

those conflicts. Early in the 20th century, other theorists offered alternative

conceptions of mental illness—but, like Freud, argued that the illness arose

from psychological processes, and not from bod-ily injury. For example, the

early behaviorists offered learning

models of mental illness, building on the mechanisms. In this view, many

mental disor-ders result from maladaptive learning and are best corrected with

remedial learning.

Modern Conceptions of Mental Disorders

Historically,

the somatogenic and psychogenic approaches were offered as sharply dis-tinct

proposals, and scholars debated the merits of one over the other. We now know

that both approaches have considerable validity. Biomedical factors play a

critical role in producing some forms of psychopathology; childhood experiences

and maladaptive learning contribute as well. As a consequence, each of these

approaches by itself is too narrow, and it would be a mistake to point to

either somatogenic or psychogenic factors as “the sole cause” of any disorder.

To understand why, let’s look more closely at the idea of cause in this domain.

DIATHESIS

- STRESS MODELS

Imagine

someone who goes through a difficult experience—perhaps the breakup of a

long-term relationship—and subsequently becomes depressed. We might be tempted

to say that the breakup caused the depression, but the breakup was not the only

force in play here. Many people experience breakups without becoming depressed;

this tells us that a breakup will cause depression only if other factors are

present.

What

are those other factors? Part of the answer lies in a person’s biology,

because, as we will see, some people have a genetic tendency toward depression.

This tendency remains unexpressed (and so the person suffers no depression)

until the person expe-riences a particularly stressful event. Then, when that

stressful event takes place, the combination of the event plus the biological

tendency will likely lead to depression.

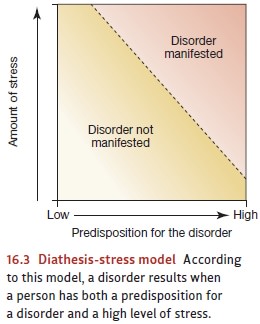

This

example suggests that we need a two-part theory of depression, and the same is

true for virtually every other form of psychopathology as well. This two-part

conception is referred to as a diathesis-stress

model (Bleuler, 1963; Meehl, 1962; Rosenthal, 1963), with one set of

factors (the diathesis) creating a

predisposition for the disorder, and a dif-ferent set of factors (the stress) providing the trigger that turns

the potential into the actual disorder (Figures 16.3). Notice that, by this

model, neither the diathesis nor the stress by itself causes the disorder;

instead, the disorder emerges only if both are present.

MULTICAUSAL MODELS

In

many cases, the diathesis takes the form of a genetic tendency—one that makes a

person vulnerable to depression if, during his lifetime, he encounters a

significant source of stress. It’s the combination of the vulnerability plus

the stress that leads to the illness. In other cases, the diathesis can take a

very different form. For example, a different factor may be how a person thinks about the events he

experiences—in particular, whether he tends to see himself as somehow

responsible for stressful, negative events . But, again, this style of

thinking, by itself, does not cause depression. Instead, the style of thinking

is only a diathesis: It creates a risk

or a vulnerability to depression, and if someone has this problematic thinking

style but leads a sheltered life—protected from the many losses and

difficulties faced by others—then he may never develop depression.

Examples

like these show the power of the diathesis-stress model, but they also reveal

that the model may be too simple. Often there are multiple diatheses for a particular indi-vidual and a particular

mental illness—including genetic factors, styles of thinking, and more.

Likewise, multiple factors often create the stress, including combinations of

harsh circumstances (for example, relationship difficulties or ongoing health

concerns) and spe-cific events (being the victim of a crime, perhaps, or

witnessing a devastating accident).

For

all these reasons, many investigators now adopt a multicausal model of depres-sion, which acknowledges that many

different factors contribute to the disorder’s emergence. Other mental

disorders also require a multicausal model. Indeed, to empha-size the diversity

of factors contributing to each disorder, most investigators now

urge

that we take a biopsychosocial

perspective, which considers biological factors (like genetics),

psychological factors (like a style of thinking), and social factors (like the

absence of social support; Figure 16.4).

Related Topics