Chapter: Psychology: Psychopathology

Defining Mental Disorders

Defining Mental Disorders

Phrases

such as “mental disorder” and “abnormal psychology” suggest that when defining

mental disorders, we should start with some conception of normalcy and then

define disorders as variations that are not normal. Thus, taking depression as

an example, we might acknowledge that everyone is occasionally sad, but we

might worry about (and try to treat) someone whose sadness is deeper and lasts

longer than normal sadness.

However,

this perspective invites difficulties, because even something normal can be

problematic. For example, almost everyone gets cavities, which makes them

normal, but this does not change the fact that cavities are a problem.

Likewise, many things are “abnormal” without necessarily being symptoms of

disorders. Pink is not a normal hair color, but this does not mean that someone

who dyes his hair pink is sick. It seems clear, therefore, that we cannot

equate being “abnormal” with being “ill.”

How,

then, should we define mental disorders? The most commonly accepted defi-nition

is the one provided by the American Psychiatric Association (2000) in the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (now in the text revisionof

its fourth edition, and hence known as the DSM-IV-TR; for the sake of

simplicity, we’ll refer to this work as DSM

from this point forward). The DSM

states that each of the mental disorders is a

Behavioral

or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in a person and that is

asso-ciated with present distress (e.g., a painful symptom) or disability

(i.e., impairment in one or more important areas of functioning) or with a

significantly increased risk of suffering death, pain, disability, or an

important loss of freedom. In addition, this syndrome or pattern must not be

merely an expectable and culturally sanctioned response to a particular event,

for example, the death of a loved one. Whatever its origi-nal cause, it must

currently be considered a manifestation of a behavioral, psychological, or

biological dysfunction in the individual.

Notice

that this is a functional definition—it focuses on distress and disability—

rather than one that specifies the causes or origins of the problem. Notice too

the requirement that the behaviors in question be not “expectable and

culturally sanc-tioned.” This aspect of the definition is important, because

what is expectable varies across cultures and over time, and so it’s valuable

to remind ourselves that we need to take social context into account when

assessing an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

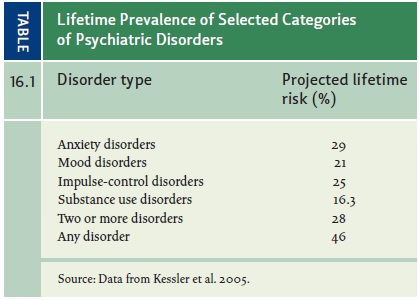

Using

this definition, we can tackle a crucial question: Just how common is mental

illness? Are we considering problems that are, in fact, relatively rare? Or is

mental illness common? Table 16.1 shows the prevalence of different psychiatric

disor-ders in the United States. The term prevalence

refers to how widespread a disorder is, and researchers typically consider two

types of prevalence. Point prevalence

refers to how many peo-ple in a given population have a given disorder at a

particular point in time. Lifetime

prevalence refers to how many people in a certain population will have the

disorder at any point in their lives. Reviewing this table, we can see that

nearly half of the U.S. population (46%) will experience at least one mental

disorder during their lifetimes, and more than a quarter (28%) will experience

two or more disorders. Most common are anxi-ety disorders (lifetime prevalence

rate of 29%) and impulse-control disorders (lifetime prevalence rate of 25%).

These statistics make it clear that large numbers of people suffer mental

disorders directly, and of course an even larger number of people (the friends,

family members, co-workers, and neighbors of the mentally ill) suffer

indirectly. We are, in short, talking

about a problem that is severe and widespread.

Related Topics