Chapter: Psychology: Psychopathology

Eating Disorders

Eating Disorders

Two

different eating disorders are identified by the DSM. The first—anorexia

nervosa— is defined by a refusal to maintain a minimally appropriate body

weight. The second— bulimia nervosa—is

defined by an alternating sequence of “binges” and “purges”—rapidfood intake

followed by maladaptive (and often extreme) attempts to keep from gain-ing

weight.

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

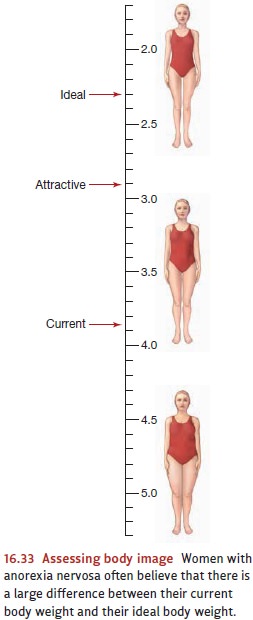

Individuals

with anorexia nervosa are

preoccupied with food and eating and have an intense fear of gaining weight.

This fear is nurtured by a disturbance in how these people perceive their own

bodies—they genuinely believe themselves to be fat, despite the fact that in

many cases they are extremely, even dangerously, thin (Figure 16.32). They

spend enormous amounts of time measuring various parts of their bodies and

critically examining themselves in the mirror. Any slight change in weight is

momentous to them, with tiny decreases celebrated and minute gains lamented

(Figure 16.33). It’s not surprising, therefore, that individuals with anorexia

nervosa relentlessly pursue thinness and usually achieve unhealthy reductions

in body weight through a regimen of incredibly strict dieting. They may also

exercise excessively or purge (self-induce vomiting or misuse laxatives or

diuretics).

The

lifetime prevalence of anorexia nervosa among females is about 0.5%, and

although men can also have anorexia nervosa, they are 10 times less likely than

women to have this disorder. Still, the features associated with anorexia

nervosa are similar for men and for women—including increased risk of

depression and substance abuse. Anorexia nervosa can begin before puberty, but

this is rare. Typically, it develops in adolescence, between the ages of 14 and

18. The prognosis varies considerably. In severe cases, anorexia nervosa can be

life-threatening, as the extreme dieting can lead to dangerous fluid and electrolyte

imbalances. Individuals with less extreme cases often recover fully, although

some continue throughout their lives to show a fluctuating pattern of weight

gain and loss.

Anorexia

nervosa has a clear genetic component (Strober, Freeman, Lampert, Diamond,

& Kaye, 2000), and a person is 10 times as likely to have anorexia ner-vosa

if she has a close relative with the disorder than if she does not.

Sociocultural factors also play a role. Anorexia nervosa is much more common in

cultures that equate being thin with being attractive than in cultures that do

not (Striegel-Moore et al., 2003).

BULIMIA NERVOSA

Like

individuals with anorexia nervosa, individuals with bulimia nervosa are extremely concerned with their weight and

appearance, and this concern fuels disordered eating behavior (Figure 16.34).

Unlike those with anorexia nervosa, however, individuals with bulimia nervosa

often have normal weight (Hsu, 1990). What marks this disorder is the

combination of binge eating and compensatory behavior (Wilson & Pike,

2001). Bingeeating refers to eating

a large amount of food within a relatively brief time period (e.g.,2 hours),

usually while feeling little or no control over what or how much one eats. Compensatory behavior refers to the

actions taken to try to ensure that the binge eat-ing does not translate into

weight gain—including self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives or diuretics,

or extreme levels of exercise.

Because

people with bulimia nervosa feel shame about their binges, they often try to

hide their behavior from others and may spend considerable time planning their

secre-tive eating sessions. When they do binge, the targeted foods are

typically high-calorie “junk” foods such as donuts, cake, or ice cream.

Many people binge at one point or another, and some occasionally purge. The DSM diagnosis for bulimia nervosa applies only if a person exhibits binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors at least twice a week for at least 3 months. By this definition, the lifetime prevalence of bulimia nervosa among women is approximately 1 to 3% and—as with anorexia nervosa—it is approximately 10 times more common in women than in men. The onset of bulimia nervosa is usu-ally late adolescence, and over the long term, the ill-ness can lead to many health problems. For example, women whose compensatory behaviors include purging may develop fluid and electrolyte imbalances. The vomiting that is usually associated with bulimia nervosa leads to a significant erosion of dental enamel, giving teeth a worn and yellowed look.

Both

genetic and sociocultural factors contribute to the onset and maintenance of

bulimia nervosa. Women who have close relatives with bulimia nervosa are four

times more likely to have this disorder than are women who do not (Strober et

al., 2000). In addition, research suggests that bulimia nervosa may be confined

to westernized cul-tural contexts (Keel & Klump, 2003); as cultures become

more westernized, rates of bulimia nervosa increase (Nasser, 1997).

Related Topics