Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Antiseizure Drugs

Seizure Classification - Clinical Pharmacology of Antiseizure Drugs

CLINICAL

PHARMACOLOGY OF ANTISEIZURE DRUGS

SEIZURE CLASSIFICATION

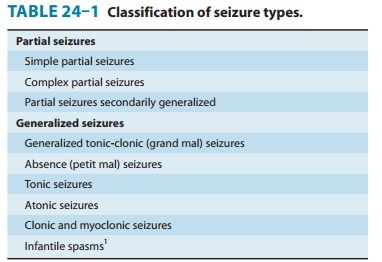

In

general, the type of medication used for epilepsy depends on the empiric nature

of the seizure. For this reason, considerable effort has been expended to classify

seizures so that clinicians will be able to make a “seizure diagnosis” and on

that basis prescribe appropriate therapy. Errors in seizure diagnosis cause use

of the wrong drugs, and an unpleasant cycle ensues in which poor seizure

control is followed by increasing drug doses and medication toxic-ity. As

noted, seizures are divided into two groups: partial and generalized. Drugs

used for partial seizures are more or less the same for all subtypes of partial

seizures, but drugs used for general-ized seizures are determined by the

individual seizure subtype. A summary of the international classification of

epileptic seizures is presented in Table 24–1.

Partial Seizures

Partial

seizures are those in which a localized onset of the attack can be ascertained,

either by clinical observation or by electroen-cephalographic recording; the

attack begins in a specific locus in the brain. There are three types of

partial seizures, determined to some extent by the degree of brain involvement

by the abnormal discharge. The least complicated partial seizure is the simple partialseizure, characterized by

minimal spread of the abnormal dischargesuch that normal consciousness and

awareness are preserved. For example, the patient may have a sudden onset of

clonic jerking of an extremity lasting 60–90 seconds; residual weakness may

last for 15–30 minutes after the attack. The patient is completely aware of the

attack and can describe it in detail. The electroencephalogram may show an

abnormal discharge highly localized to the involved portion of the brain.

The

complex partial seizure also has a

localized onset, but the discharge becomes more widespread (usually bilateral)

and almost always involves the limbic system. Most complex partial seizures

arise from one of the temporal lobes, possibly because of the susceptibility of

this area of the brain to insults such as hypoxia or infection. Clinically, the

patient may have a brief warning followed by an alteration of consciousness

during which some patients stare and others stagger or even fall. Most,

however, demonstrate fragments of integrated motor behavior called automatisms for which the patient has

no memory. Typical automatisms are lip smacking, swallowing, fumbling,

scratching, and even walking about. After 30–120 seconds, the patient makes a

gradual recovery to normal consciousness but may feel tired or ill for several

hours after the attack.

The

last type of partial seizure is the secondarily

generalizedattack, in which a partial seizure immediately precedes a

general-ized tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizure. This seizure type is described

in the text that follows.

Generalized Seizures

Generalized

seizures are those in which there is no evidence of localized onset. The group

is quite heterogeneous.

Generalized tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizures are the

mostdramatic of all epileptic seizures and are characterized by tonic rigidity

of all extremities, followed in 15–30 seconds by a tremor that is actually an

interruption of the tonus by relaxation. As the relaxation phases become

longer, the attack enters the clonic phase, with massive jerking of the body.

The clonic jerking slows over 60–120 seconds, and the patient is usually left

in a stuporous state. The tongue or cheek may be bitten, and urinary inconti-nence

is common. Primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures begin without evidence of

localized onset, whereas secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures are

preceded by another seizure type, usually a partial seizure. The medical

treatment of both primary and secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures is

the same and uses drugs appropriate for partial

seizures.

The

absence (petit mal) seizure is

characterized by both sudden onset and abrupt cessation. Its duration is

usually less than 10 seconds and rarely more than 45 seconds. Consciousness is

altered; the attack may also be associated with mild clonic jerking of the

eyelids or extremities, with postural tone changes, auto-nomic phenomena, and

automatisms. The occurrence of automa-tisms can complicate the clinical

differentiation from complex partial seizures in some patients. Absence attacks

begin in child-hood or adolescence and may occur up to hundreds of times a day.

The electroencephalogram during the seizure shows a highlycharacteristic 2.5–3.5

Hz spike-and-wave pattern. Atypical absence patients have seizures with

postural changes that are more abrupt, and such patients are often mentally

retarded; the electroencepha-logram may show a slower spike-and-wave discharge,

and the sei-zures may be more refractory to therapy.

Myoclonic jerking is seen, to a greater or lesser extent, in

awide variety of seizures, including generalized tonic-clonic sei-zures,

partial seizures, absence seizures, and infantile spasms. Treatment of seizures

that include myoclonic jerking should be directed at the primary seizure type

rather than at the myoclonus. Some patients, however, have myoclonic jerking as

the major sei-zure type, and some have frequent myoclonic jerking and

occa-sional generalized tonic-clonic seizures without overt signs of neurologic

deficit. Many kinds of myoclonus exist, and much effort has gone into attempts

to classify this entity.

Atonic seizures are those in which the patient has sudden

lossof postural tone. If standing, the patient falls suddenly to the floor and

may be injured. If seated, the head and torso may suddenly drop forward.

Although most often seen in children, this seizure type is not unusual in

adults. Many patients with atonic seizures wear helmets to prevent head injury.

Momentary increased tone may be

observed in some patients, hence the use of the term “tonic-atonic seizure.”

Infantile spasms are an epileptic syndrome and not a

seizuretype. The attacks, though sometimes fragmentary, are most often

bilateral and are included for pragmatic purposes with the general-ized

seizures. These attacks are most often characterized clinically by brief,

recurrent myoclonic jerks of the body with sudden flex-ion or extension of the

body and limbs; the forms of infantile spasms are, however, quite

heterogeneous. Ninety percent of affected patients have their first attack

before the age of 1 year. Most patients are intellectually delayed, presumably

from the same cause as the spasms. The cause is unknown in many patients, but

such widely disparate disorders as infection, kernicterus, tuberous sclerosis,

and hypoglycemia have been implicated. In some cases, the electroencephalogram

is characteristic. Drugs used to treat infantile spasms are effective only in

some patients; there is little evidence that the cognitive retardation is

alleviated by therapy, even when the attacks disappear.

Related Topics