Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Urinary Disorders

Lower Urinary Tract Infections

LOWER

URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

Several

mechanisms maintain the sterility of the bladder: the physical barrier of the

urethra, urine flow, ureterovesical junction competence, various antibacterial

enzymes and antibodies, and antiadherent effects mediated by the mucosal cells

of the bladder. Abnormalities or dysfunctions of these mechanisms are

con-tributing factors to lower UTIs (Chart 45-2).

Pathophysiology

For

infection to occur, bacteria must gain access to the bladder, attach to and

colonize the epithelium of the urinary tract to avoid being washed out with

voiding, evade host defense mechanisms, and initiate inflammation. Most UTIs

result from fecal organ-isms that ascend from the perineum to the urethra and

the blad-der and then adhere to the mucosal surfaces.

BACTERIAL INVASION OF THE URINARY TRACT

By

increasing the normal slow shedding of bladder epithelial cells (resulting in

bacteria removal), the bladder can clear itself of even large numbers of

bacteria. Glycosaminoglycan (GAG), a hydro-philic protein, normally exerts a

nonadherent protective effect against various bacteria. The GAG molecule

attracts water mol-ecules, forming a water barrier that serves as a defensive

layer be-tween the bladder and the urine. GAG may be impaired by certain agents

(cyclamate, saccharin, aspartame, and tryptophan metabolites). The normal

bacterial flora of the vagina and ure-thral area also interfere with adherence

of Escherichia coli (the most common

microorganism causing UTI). Urinary immuno-globulin A (IgA) in the urethra may

also provide a barrier to bacteria.

REFLUX

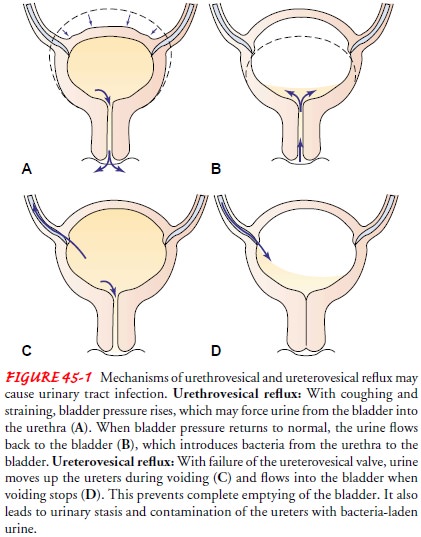

An

obstruction to free-flowing urine is a problem known as ure-throvesical reflux, which is the reflux (backward flow) of

urinefrom the urethra into the bladder (Fig. 45-1). With coughing, sneezing, or

straining, the bladder pressure rises, which may force urine from the bladder

into the urethra. When the pressure returns to normal, the urine flows back

into the bladder, bringing into the bladder bacteria from the anterior portions

of the urethra. Ure-throvesical reflux is also caused by dysfunction of the

bladder neck or urethra. The urethrovesical angle and urethral closure pressure

may be altered with menopause, increasing the incidence of infec-tion in

postmenopausal women. Reflux is most often noted, how-ever, in young children.

Treatment is based on its severity.

Ureterovesical or vesicoureteral reflux refers to the back-ward flow of urine from the bladder into one or both ureters (see Fig. 45-1). Normally, the ureterovesical junction prevents urine from traveling back into the ureter. The ureters tunnel into the bladder wall so that the bladder musculature compresses a small portion of the ureter during normal voiding. When the uretero-vesical valve is impaired by congenital causes or ureteral abnor-malities, the bacteria may reach and eventually destroy the kidneys.

UROPATHOGENIC BACTERIA

Bacteriuria is generally defined as more than 105colonies ofbacteria per

milliliter of urine. Because urine samples (especially in women) are commonly

contaminated by the bacteria nor-mally present in the urethral area, a

bacterial count exceeding 105 colonies/mL of clean-catch midstream urine is the

measure that distinguishes true bacteriuria from contamination. In men,

contamination of the collected urine sample occurs less fre-quently; hence,

bacteriuria can be defined as 104 colonies/mL urine. Community-acquired UTIs are

among the most common bacterial infections in women (Gupta, Hooton & Stamm,

2001).

The

organisms most frequently responsible for UTIs are those normally found in the

lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In a large-scale study of the types and

prevalence of organisms of patients with UTIs in both the community and

hospital setting, E. coli was

responsible for 54.7% of urinary tract infections. Isolation of E. coli is decreasing in comparison to

previous observations, especially in males and in patients with indwelling

bladder catheters, who instead had higher rates of Pseudomonas and En-terococcus

organisms than females and noncatheterized patients(Bonadio, Meini,

Spitaleri & Gigli, 2001).

ROUTES OF INFECTION

There

are three well-recognized routes by which bacteria enter the urinary tract: up

the urethra (ascending infection), through the bloodstream, (hematogenous

spread), or by means of a fistula from the intestine (direct extension).

The

most common route of infection is transurethral, in which bacteria (often from

fecal contamination) colonize the periurethral area and subsequently enter the

bladder by means of the urethra. In women, the short urethra offers little

resistance to the movement of uropathogenic bacteria. Sexual intercourse or

massage of the urethra forces the bacteria up into the bladder. This accounts

for the increased incidence of UTIs in sexually ac-tive women. Bacteria may

also enter the urinary tract by means of the blood (hematogenous spread) from a

distant site of infec-tion or through direct extension by way of a fistula from

the in-testinal tract.

Clinical Manifestations

A

variety of signs and symptoms are associated with UTI. About half of all

patients with bacteriuria have no symptoms. Signs and symptoms of uncomplicated

lower UTI (cystitis) include fre-quent pain and burning on urination,

frequency, urgency, noc-turia, incontinence, and suprapubic or pelvic pain. Hematuria

and back pain may also be present. In older individuals, these typ-ical

symptoms are seldom noted (see Gerontologic Considera-tions, below).

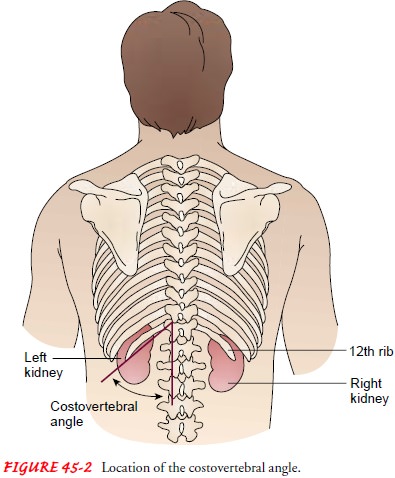

Signs

and symptoms of upper UTI (pyelonephritis) include fever, chills, flank or low

back pain, nausea and vomiting, head-ache, malaise, and painful urination.

Physical examination re-veals pain and tenderness in the area of the

costovertebral angles (CVA), which are the angles formed on each side of the

body by the bottom rib of the rib cage and the vertebral column (Fig. 45-2).

In patients with complicated UTIs, such as those with in-dwelling catheters, manifestations can range from asymptomatic bacteriuria to a gram-negative sepsis with shock. Complicated UTIs often are due to a broader spectrum of organisms, have a lower response rate to treatment, and tend to recur. Many pa-tients with catheter-associated UTIs are asymptomatic; however, any patient who suddenly develops signs and symptoms of septic shock should be evaluated for urosepsis.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Results

of various tests, such as colony counts, cellular studies, and urine cultures,

help confirm the UTI diagnosis. The Ameri-can College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists (ACOG) recom-mends that all pregnant women be screened for

asymptomatic bacteriuria since pregnancy itself is a risk factor for UTI

because the bladder does not empty as well as it normally does. In an

un-complicated UTI, the strain of bacteria will determine the anti-biotic of

choice.

COLONY COUNTS

UTI is

diagnosed by bacteria in the urine. A colony count of at least 105 colony-forming units

(CFU) per milliliter of urine on a clean-catch midstream or catheterized

specimen is a major crite-rion for infection. However, UTI and subsequent

sepsis have oc-curred with lower bacterial colony counts. About one third of

women with symptoms of acute infections have negative mid-stream urine culture

results and may go untreated if 105 CFU/mL is used as the criterion for

infection. The presence of any bacte-ria in specimens obtained by suprapubic

needle aspiration of the urinary bladder or catheterization is considered

indicative of infection.

CELLULAR STUDIES

Microscopic

hematuria (greater than 4 red blood cells [RBCs] per high-power field) is

present in about half of patients with acute infection. Pyuria (greater than 4 white blood cells [WBCs] per high-power

field) occurs in all patients with UTI; however, it is not specific for

bacterial infection. Pyuria can also be seen with kidney stones, interstitial

nephritis, and renal tuberculosis.

URINE CULTURES

Urine

cultures remain the gold standard in documenting a UTI and can identify the

specific organism present. Because of the high probability that the organism in

young women with their first UTI is E.

coli, cultures are often omitted. The following groups of patients should

have urine cultures obtained when bacteriuria is present:

· All men (because of the

likelihood of structural or func-tional abnormalities)

· All children

· Women with a history of

compromised immune function or renal problems

· Patients with diabetes

mellitus

· Patients who have

undergone recent instrumentation (in-cluding catheterization) of the urinary

tract

· Patients who were

hospitalized recently

· Patients with prolonged

or persistent symptoms

· Patients with three or

more UTIs in the past year

· Pregnant women

· Postmenopausal women

·

Women who are sexually active or have new partners

TESTING METHODS

Multistrip

dipstick testing for WBCs, known as the leukocyte es-terase test, and nitrite

testing (Griess nitrate reduction test) are common. If the leukocyte esterase

test is positive, it is assumed that the patient has pyuria (WBCs in the urine)

and should be treated. The Griess nitrate reduction test is considered positive

if bacteria that reduce normal urinary nitrates to nitrites are present.

Tests

for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) may be per-formed because acute

urethritis caused by sexually transmitted or-ganisms (ie, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, herpes simplex) or

acute vaginitis infections (caused by Trichomonas

or Candida species) may be

responsible for symptoms similar tothose of UTI. Therefore, evaluation for STDs

may be performed.

Historically,

intravenous pyelography (IVP) was used to detect abnormalities in patients at

high risk for complicated or recurring UTI. Today, diagnostic studies such as

computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography are preferred detection methods

for several reasons: CT scans may detect areas of pyelonephritis or ab-scesses,

and ultrasonography is extremely sensitive for detecting obstruction,

abscesses, tumors, and cysts. Transrectal ultrasonog-raphy (to assess the

prostate and bladder) is the procedure of choice for men with recurrent or

complicated UTIs. An IVP may be indicated to visualize the ureters or to detect

strictures or stones and is necessary for an accurate diagnosis of reflux

nephropathy. It is generally accepted that the first episode of UTI in women

does not require urologic evaluation (Hooton, Scholes, Stapleton et al., 2000).

Gerontologic Considerations

The

incidence of bacteriuria in the elderly differs from that in younger adults.

Bacteriuria increases with age and disability, and women are affected more

frequently than men. UTI is the most common cause of acute bacterial sepsis in

patients older than 65 years of age, in whom gram-negative sepsis carries a

mortality rate exceeding 50%. Urologists see many asymptomatic older pa-tients

with bacteriuria, and these individuals represent 20% of women over the age of

65. In the nursing home environment, up to 50% of females have asymptomatic

bacteriuria (Foxman, 2002).

In the

elderly population at large, structural abnormalities and neurogenic bladder

secondary to strokes or autonomic neuropa-thy of diabetes may prevent complete

emptying of the bladder and increase the risk for UTI. When indwelling

catheters are used, the risk for UTI rises dramatically as two or more

different strains of bacteria can be found in the urine of catheterized

pa-tients: in the urine itself, and on the surface of the catheter. El-derly

women often have incomplete emptying of the bladder and urinary stasis. In the

absence of estrogen, postmenopausal women are susceptible to colonization and

increased adherence of bacte-ria to the vagina and urethra. Oral or topical

estrogen has been used to restore the glycogen content of vaginal epithelial

cells and an acidic pH for some postmenopausal women with recurrent cystitis.

Local estrogen replacement may reduce the rate of UTIs in postmenopausal women

with recurrent UTIs (Raz, 2001).

The

antibacterial activity of prostatic secretions that protects men from bacterial

colonization of the urethra and bladder de-creases with aging. Although UTIs

are rare in men, the prevalence of infection in men older than 50 years of age

approaches that of women in the same age group. The dramatic rise in UTI in men

as they age is due largely to prostatic hyperplasia or carcinoma, strictures of

the urethra, and neuropathic bladder. The use of catheterization or cystoscopy

in evaluation or treatment may con-tribute further to the higher incidence of

UTI. The incidence of bacteriuria rises in men with confusion, dementia, or

bowel or bladder incontinence. The most common cause of recurrent UTI in the

elderly male patient is chronic bacterial prostatitis.

Transurethral

resection of the prostate gland may help to reduce its incidence.

In

institutionalized elderly patients, such as those in nursing homes, infecting

pathogens are often resistant to many antibi-otics. Factors that may contribute

to UTI in elderly nursing home patients include: high incidence of chronic

illness; frequent use of antimicrobial agents; infected pressure ulcers;

immobility and incomplete emptying of the bladder; and use of a bedpan rather

than a commode or toilet (Chart 45-3).

Diligent

hand hygiene, careful perineal care, and frequent toi-leting may decrease the

incidence of UTIs in nursing home pa-tients. The organisms responsible for UTIs

in the institutionalized elderly may differ from those found in patients

residing in the community; this is thought to be due in part to the frequent

use of antibiotic agents by patients in nursing homes. E. coli is the most common organism seen in elderly patients in the

commu-nity or hospital. Patients with indwelling catheters, however, are more

likely to be infected with Proteus,

Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, or Staphylococcus

species. Patients who have been previously treated with antibiotics may be

infected with Enterococcus species.

Fre-quent reinfections are common in older adults.

The

most common subjective presenting symptom of UTI in older adults is generalized

fatigue. The most common objective finding is a change in cognitive

functioning, especially in those with dementia, because these patients usually

exhibit even more profound cognitive changes with the onset of a UTI.

Medical Management

Management

of UTIs typically involves pharmacologic therapy and patient education. The

nurse is a key figure in teaching the patient about medication regimens and infection

prevention measures.

Controversy

continues about the need for treatment of asymp-tomatic bacteriuria in the

institutionalized elderly patient be-cause resulting antibiotic-resistant

organisms and sepsis may be greater threats to the patient. Most experts now

recommend with-holding antibiotics unless symptoms develop. Treatment

regi-mens, however, are generally the same as those for younger adults,

although age-related changes in the intestinal absorption of medications and

decreased renal function and hepatic flow may necessitate alterations in the

antimicrobial regimen. Renal function must be monitored and the dosage of

medications altered accordingly.

ACUTE PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

The

ideal treatment of UTI is an antibacterial agent that eradi-cates bacteria from

the urinary tract with minimal effects on fecal and vaginal flora, thereby

minimizing the incidence of vaginal yeast infections. (Yeast vaginitis occurs

in as many as 25% of pa-tients treated with antimicrobial agents that affect

vaginal flora. Yeast vaginitis often causes more symptoms and is more difficult

and costly to treat than the original UTI.) Additionally, the anti-bacterial

agent should be affordable and should produce few ad-verse effects and low

resistance. Because the organism in initial, uncomplicated UTIs in women is

most likely E. coli or other fecal

flora, the agent should be effective against these organisms. Various treatment

regimens have been successful in treating un-complicated lower UTIs in women:

single-dose administration, short-course (3 to 4 days) medication regimens, or

7- to 10-day therapeutic courses. The trend is toward a shortened course of

anti-biotic therapy for uncomplicated UTIs because about 80% of cases are cured

after 3 days of treatment.

In a

complicated UTI (ie, pyelonephritis), the general treatment of choice is

usually a cephalosporin or an ampicillin/amino-glycoside combination. Patients

in institutional settings may re-quire 7 to 10 days of medication for the

treatment to be effective. Other commonly used medications include

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ, Bactrim, Septra) and nitrofurantoin

(Macrodantin, Furadantin). Occasionally, medications such as ampicillin or

amoxicillin are used, but E. coli

organisms have de-veloped resistance to these agents. Recent clinical trials

compar-ing the use of TMP-SMZ and the fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin (Cipro)

found ciprofloxacin to be significantly more effective in community-based

patients and in nursing home residents (Gomolin & McCue, 2000; Talan et al.,

2000).

Levofloxacin

(Levaquin), another fluoroquinolone, is a good choice for short-course therapy

of uncomplicated, mild to mod-erate UTI. Clinical trial data show high patient

compliance with the 3-day regimen (95.6%) and a high eradication rate for all

pathogens (96.4%). Before using levofloxacin in patients with complicated UTIs,

the causative pathogen should be identified. Levofloxacin is used only when

generic and less costly antibiotics are likely to be ineffective (Bonapace et

al., 2000).

Nitrofurantoin

should not be used in patients with renal in-sufficiency because it is

ineffective at glomerular filtration rates (GFRs) of less than 50 mL/min and

may cause peripheral neurop-athy. Phenazopyridine (Pyridium), a urinary

analgesic, may be prescribed to relieve the discomfort associated with the

infection.

Regardless

of the regimen prescribed, the patient is instructed to take all the doses

prescribed, even if relief of symptoms occurs promptly. Longer medication

courses are indicated for men, preg-nant women, and women with pyelonephritis

and other types of complicated UTIs. In pregnant women, amoxicillin,

ampicillin, or an oral cephalosporin is used for 7 to 10 days.

LONG-TERM PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Although

brief pharmacologic treatment of UTI for 3 days is usu-ally adequate in women,

infection recurs in about 20% of women treated for uncomplicated UTI.

Infections that recur within 2 weeks after therapy (referred to as a relapse)

do so because or-ganisms of the original offending strain remain in the vagina.

Re-lapses suggest that the source of bacteriuria may be the upper urinary tract

or that initial treatment was inadequate or adminis-tered for too short a time.

Recurrent infections in men are usu-ally due to persistence of the same

organism; further evaluation and treatment are indicated (Gupta et al., 2001;

Hooton et al., 2000; Stamm, 2001).

Reinfection

of the female patient with new bacteria is the rea-son for more than 90% of

recurrent UTIs in women. If the di-agnostic evaluation reveals no structural

abnormalities in the urinary tract, the woman with recurrent UTIs may be

instructed to begin treatment on her own whenever symptoms occur and to contact

the health care provider only when symptoms persist, fever occurs, or the

number of treatment episodes exceeds four in a 6-month period. This patient may

be taught to use dip-slide culture devices to detect bacteria.

If

infection recurs after completing antimicrobial therapy, another short course

(3 to 4 days) of full-dose antimicrobial therapy followed by a regular bedtime

dose of an antimicrobial agent may be prescribed. If there is no recurrence,

medication is taken every other night for 6 to 7 months. Other options in-clude

a dose of an antimicrobial agent after sexual intercourse, a dose at bedtime,

or a dose every other night or three times per week. Long-term use of

antimicrobial agents decreases the risk of reinfection and may be indicated in

patients with recurrent infections.

If

recurrence is caused by persistent bacteria from preceding infections, the

cause (ie, kidney stone, abscess), if known, must be treated. After treatment

and sterilization of the urine, low-dose preventive therapy (trimethoprim with

or without sulfamethox-azole) each night at bedtime is often prescribed.

Evidence

about the effectiveness of daily intake of cranberry extract or cranberry juice

to prevent UTIs in women is conflict-ing, although most randomized studies

point to a decrease in UTIs in women consuming daily cranberry juice

(Kontiokari, Sundqvist & Nuutinen, 2001).

Related Topics