Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Urinary Disorders

Cancer of the Bladder

CANCER

OF THE BLADDER

Cancer

of the urinary bladder is more common in people aged 50 to 70 years. It affects

men more than women (3:1) and is more common in whites than in African

Americans. Bladder cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer in American

men, accounting for more than 12,000 deaths in the U.S. annually (American

Cancer Society, 2002). Bladder cancer has a high worldwide in-cidence (Amling,

2001). Bladder tumors account for nearly 1 in 25 cancers diagnosed in the

United States. There are two forms of bladder cancer: superficial (which tends

to recur) and invasive. About 80% to 90% of all bladder cancers are

transitional cell (which means they arise from the transitional cells of the

blad-der); the remaining types of tumors are squamous cell and ade-nocarcinoma.

Research has demonstrated that many individuals with bladder cancer for which a

total cystectomy is required go on to develop upper urinary tract tumors

(Amling, 2001; Huguet-Perez, Palui, Millan-Rodriguez et al., 2001).

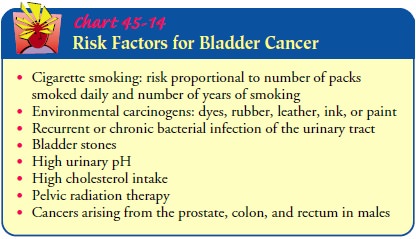

The

predominant cause of bladder cancer today is cigarette smoking. Cancers arising

from the prostate, colon, and rectum in males and from the lower gynecologic

tract in females may metas-tasize to the bladder (Chart 45-14).

Clinical Manifestations

Bladder

tumors usually arise at the base of the bladder and involve the ureteral

orifices and bladder neck. Visible, painless hematuria is the most common

symptom of bladder cancer. Infection of the urinary tract is a common

complication, producing frequency, urgency, and dysuria. Any alteration in

voiding or change in the urine, however, may indicate cancer of the bladder.

Pelvic or back pain may occur with metastasis.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The

diagnostic evaluation includes cystoscopy (the mainstay of diagnosis),

excretory urography, a CT scan, ultrasonography, and bimanual examination with

the patient anesthetized. Biopsies of the tumor and adjacent mucosa are the

definitive diagnostic pro-cedures. Transitional cell carcinomas and carcinomas

in situ shed recognizable cancer cells. Cytologic examination of fresh urine

and saline bladder washings provide information about the prog-nosis,

especially for patients at high risk for recurrence of primary bladder tumors

(Amling, 2001).

Although

mainstay diagnostic tools such as cytology and CT scanning have a high

detection rate, they are costly. Newer diag-nostic indicators are being

studied. Bladder tumor antigens, nu-clear matrix proteins, adhesion molecules,

cytoskeletal proteins, and growth factors are being studied to support the

early detec-tion and diagnosis of bladder cancer. There are an increasing

number of molecular assays available for the detection of bladder cancer (Saad,

Hanbury, McNicholas et al., 2001).

Medical Management

Treatment

of bladder cancer depends on the grade of the tumor (the degree of cellular

differentiation), the stage of tumor growth (the degree of local invasion and

the presence or absence of metas-tasis), and the multicentricity (having many

centers) of the tumor. The patient’s age and physical, mental, and emotional

sta-tus are considered when determining treatment modalities.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Transurethral resection or fulguration (cauterization) may be per-formed for simple papillomas (benign epithelial tumors). These procedures, eradicate the tumors through surgical incision or electrical current with the use of instruments inserted through the urethra. After this bladder-sparing surgery, intravesical administration of BCG is the treat-ment of choice.

Management

of superficial bladder cancers presents a challenge because there are usually

widespread abnormalities in the bladder mucosa. The entire lining of the

urinary tract, or urothelium, is at risk because carcinomatous changes can

occur in the mucosa of the bladder, renal pelvis, ureter, and urethra. About

25% to 40% of superficial tumors recur after transurethral resection or

fulgu-ration. Patients with benign papillomas should undergo cytology and

cystoscopy periodically for the rest of their lives because ag-gressive

malignancies may develop from these tumors.

A simple

cystectomy (removal of the bladder)

or a radical cystectomy is performed for invasive or multifocal bladder

can-cer. Radical cystectomy in men involves removal of the bladder, prostate,

and seminal vesicles and immediate adjacent perivesical tissues. In women,

radical cystectomy involves removal of the blad-der, lower ureter, uterus,

fallopian tubes, ovaries, anterior vagina, and urethra. It may include removal

of pelvic lymph nodes. Re-moval of the bladder requires a urinary diversion

procedure.

Although

radical cystectomy remains the standard of care for invasive bladder cancer in

the United States, researchers are ex-ploring trimodality therapy:

transurethral resection of the blad-der tumor, radiation, and chemotherapy.

This is in an effort to spare patients the need for cystectomy. A trimodality

approach to transitional cell bladder cancer mandates lifelong surveillance

with cystoscopy. Although most completely responding patients retain their

bladders free from invasive relapse, one quarter de-velop superficial disease.

This may be managed with transurethral resection of the bladder tumor and

intravesical therapies but carries an additional risk that late cystectomy will

be required (Zietman, Grocela & Zehr, 2001; Zietman, Shipley & Kaufman,

2000).

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Chemotherapy

with a combination of methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil, vinblastine, doxorubicin

(Adriamycin), and cisplatin has been ef-fective in producing partial remission

of transitional cell carci-noma of the bladder in some patients. Intravenous

chemotherapy may be accompanied by radiation therapy. The development of new

chemotherapeutic agents such as gemcitabine and the tax-anes has opened up

promising new perspectives in the treatment of bladder cancer. However, the

preliminary phase II data must be confirmed in adequately conducted phase III

trials (Bellmunt & Albiol, 2001).

Topical

chemotherapy (intravesical chemotherapy or instilla-tion of antineoplastic

agents into the bladder, resulting in contact of the agent with the bladder

wall) is considered when there is a high risk for recurrence, when cancer in

situ is present, or when tumor resection has been incomplete. Topical

chemotherapy de-livers a high concentration of medication (thiotepa,

doxorubicin, mitomycin, ethoglucid, and BCG) to the tumor to promote tumor

destruction. BCG is now considered the most effective in-travesical agent for

recurrent bladder cancer because it enhances the body’s immune response to

cancer.

Intravesical

BCG is an immunotherapeutic agent that is given intravesically and is effective

in the treatment of superficial tran-sitional cell carcinoma. BCG has a 43%

advantage in preventing tumor recurrence, a significantly better rate than the

16% to 21% advantage of intravesical chemotherapy. In addition, BCG is

par-ticularly effective in the treatment of carcinoma in situ, eradicat-ing it

in more than 80% of cases. In contrast to intravesical chemotherapy, BCG has

also been shown to decrease the risk of tumor progression.

The

optimal course of BCG appears to be a 6-week course of weekly instillations,

followed by a 3-week course at 3 months in tumors that do not respond. In

high-risk cancers, maintenance BCG administered for 3 weeks every 6 months may

limit recur-rence and prevent progression (Amling, 2001). The adverse ef-fects

associated with this prolonged therapy, however, may limit its widespread

applicability.

The

patient is allowed to eat and drink before the instillation procedure, but once

the bladder is full, the patient must retain the intravesical solution for 2

hours before voiding. At the end of the procedure, the patient is encouraged to

void and to drink lib-eral amounts of fluid to flush the medication from the

bladder.

RADIATION THERAPY

Radiation

of the tumor may be performed preoperatively to re-duce microextension of the

neoplasm and viability of tumor cells, thus reducing the chances that the

cancer may recur in the im-mediate area or spread through the circulatory or

lymphatic sys-tems. Radiation therapy is also used in combination with surgery

or to control the disease in patients with an inoperable tumor. The

transitional cell variety of bladder cancer responds poorly to chemotherapy.

Cisplatin, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide have been administered in various

doses and schedules and ap-pear most effective.

Bladder

cancer may also be treated by direct infusion of the cytotoxic agent through

the bladder’s arterial blood supply to achieve a higher concentration of the

chemotherapeutic agent with fewer systemic toxic effects. For more advanced

bladder can-cer or for patients with intractable hematuria (especially after

ra-diation therapy), a large, water-filled balloon placed in the bladder

produces tumor necrosis by reducing the blood supply of the bladder wall

(hydrostatic therapy). The instillation of formalin, phenol, or silver nitrate

relieves hematuria and strangury (slow and painful discharge of urine) in some

patients.

INVESTIGATIONAL THERAPY

The

use of photodynamic techniques in treating superficial blad-der cancer is under

investigation. This procedure involves systemic injection of a photosensitizing

material (hematoporphyrin), which the cancer cell picks up. A laser-generated

light then changes the hematoporphyrin in the cancer cell into a toxic

medication. This process is being investigated for patients in whom

intravesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy has failed (Amling, 2001).

Related Topics