Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Urinary Disorders

Chronic Renal Failure (End-Stage Renal Disease)

CHRONIC

RENAL FAILURE (END-STAGE RENAL DISEASE)

Chronic

renal failure, or ESRD, is a progressive, irreversible de-terioration in renal

function in which the body’s ability to main-tain metabolic and fluid and

electrolyte balance fails, resulting in uremia or azotemia (retention of urea

and other nitrogenous wastes in the blood).

The

incidence of ESRD has increased by almost 8% per year for the past 5 years,

with more than 300,000 patients being treated in the United States (USRDS,

2001).

ESRD

may be caused by systemic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus (leading cause);

hypertension; chronic glomerulonephri-tis; pyelonephritis; obstruction of the

urinary tract; hereditary le-sions, as in polycystic kidney disease; vascular

disorders; infections; medications; or toxic agents.

Autosomal

dominant polycystic kidney disease accounts for 8% to 10% of cases of ESRD in

the United States and Europe (Perrone, Ruthazer & Terrin, 2001). Comorbid conditions

that develop during chronic renal insufficiency contribute to the high

morbidity and mortality among patients with ESRD (Kausz et al., 2001).

Environmental

and occupational agents that have been impli-cated in chronic renal failure

include lead, cadmium, mercury, and chromium. Dialysis or kidney

transplantation eventually be-comes necessary for patient survival. Dialysis is

an effective means of correcting metabolic toxicities at any age, although the

mor-tality rate in infants and young children is greater than adults in the

presence of other, nonrenal diseases and in the presence of anuria or oliguria

(Wood et al., 2001).

Pathophysiology

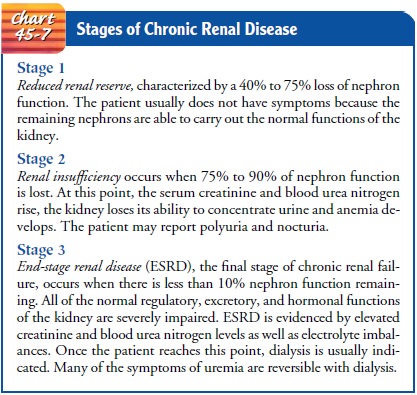

As

renal function declines, the end products of protein metabo-lism (which are

normally excreted in urine) accumulate in the blood. Uremia develops and

adversely affects every system in the body. The greater the buildup of waste

products, the more severe the symptoms. There are three well-recognized stages

of chronic renal disease: reduced renal reserve, renal insufficiency, and ESRD

(Chart 45-7).

The

rate of decline in renal function and progression of chronic renal failure is

related to the underlying disorder, the uri-nary excretion of protein, and the

presence of hypertension. The disease tends to progress more rapidly in

patients who excrete sig-nificant amounts of protein or have elevated blood

pressure than in those without these conditions.

Clinical Manifestations

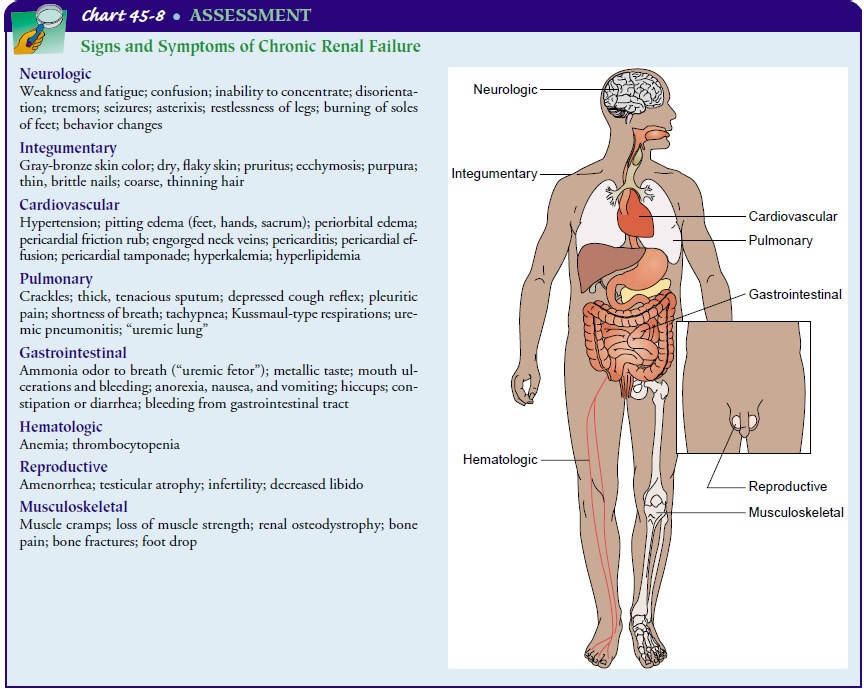

Because

virtually every body system is affected by the uremia of chronic renal failure,

patients exhibit a number of signs and symptoms. The severity of these signs

and symptoms depends in part on the degree of renal impairment, other

underlying condi-tions, and the patient’s age.

CARDIOVASCULAR MANIFESTATIONS

Hypertension

(due to sodium and water retention or from activation of the

renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system), heart failure and pulmonary edema (due

to fluid overload), and peri-carditis (due to irritation of the pericardial

lining by uremic toxins) are among the cardiovascular problems manifested in

ESRD. Strict fluid volume control has been found to normalize hyper-tension in

patients receiving peritoneal dialysis (Gunal, Duman, Ozkahya et al., 2001).

Cardiovascular

disease is the predominant cause of death in patients with ESRD. In chronic

hemodialysis patients, approxi-mately 45% of overall mortality is attributable

to cardiac disease, and about 20% of these cardiac deaths are due to acute

myocar-dial infarction (USRDS, 2001).

DERMATOLOGIC SYMPTOMS

Severe itching (pruritus) is common. Uremic frost, the deposit of urea crystals on the skin, is uncommon today because of early and aggressive treatment of ESRD with dialysis.

OTHER SYSTEMIC MANIFESTATIONS

GI

signs and symptoms are common and include anorexia, nau-sea, vomiting, and

hiccups. Neurologic changes, including al-tered levels of consciousness,

inability to concentrate, muscle twitching, and seizures, have been observed.

The precise mecha-nisms for many of these diverse signs and symptoms have not

been identified. It is generally thought, however, that the accumu-lation of

uremic waste products is the probable cause. Chart 45-8 summarizes the signs

and symptoms often seen in chronic renal failure.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

GLOMERULAR FILTRATION RATE

Decreased

GFR can be detected by obtaining a 24-hour urinaly-sis for creatinine

clearance. As glomerular filtration decreases (due to nonfunctioning

glomeruli), the creatinine clearance value de-creases, whereas the serum

creatinine and BUN levels increase. Serum creatinine is the more sensitive

indicator of renal function because of its constant production in the body. The

BUN is af-fected not only by renal disease but also by protein intake in the

diet, catabolism (tissue and RBC breakdown), parenteral nutri-tion, and

medications such as corticosteroids.

SODIUM AND WATER RETENTION

The

kidney cannot concentrate or dilute the urine normally in ESRD. Appropriate

responses by the kidney to changes in the daily intake of water and

electrolytes, therefore, do not occur. Some pa-tients retain sodium and water,

increasing the risk for edema, heart failure, and hypertension. Hypertension

may also result from ac-tivation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone axis and

the con-comitant increased aldosterone secretion. Other patients have a

tendency to lose salt and run the risk of developing hypotension and

hypovolemia. Episodes of vomiting and diarrhea may produce sodium and water

depletion, which worsens the uremic state.

ACIDOSIS

With advanced renal disease, metabolic

acidosis occurs because the kidney cannot excrete increased loads of acid.

Decreased acid secretion primarily results from inability of the kidney tubules

to excrete ammonia (NH3−) and to reabsorb sodium bicarbonate (HCO3−). There is also decreased excretion of phosphates

and other organic acids.

ANEMIA

Anemia develops as a result of inadequate erythropoietin pro-duction, the shortened life span of RBCs, nutritional deficiencies, and the patient’s tendency to bleed, particularly from the GI tract. Erythropoietin, a substance normally produced by the kid-ney, stimulates bone marrow to produce RBCs. In renal failure, erythropoietin production decreases and profound anemia re-sults, producing fatigue, angina, and shortness of breath.

CALCIUM AND PHOSPHORUS IMBALANCE

Another

major abnormality seen in chronic renal failure is a dis-order in calcium and

phosphorus metabolism. Serum calcium and phosphate levels have a reciprocal

relationship in the body: as one rises, the other decreases. With decreased

filtration through the glomerulus of the kidney, there is an increase in the

serum phosphate level and a reciprocal or corresponding decrease in the serum calcium

level. The decreased serum calcium level causes in-creased secretion of

parathormone from the parathyroid glands. In renal failure, however, the body

does not respond normally to the increased secretion of parathormone; as a

result, calcium leaves the bone, often producing bone changes and bone disease.

In addition, the active metabolite of vitamin D

(1,25-dihydroxy-cholecalciferol) normally manufactured by the kidney decreases

as renal failure progresses. Uremic bone disease, often called renal osteodystrophy,

develops from the complex changes in calcium, phosphate, and parathormone

balance (Barnas, Schmidt, Seidl et al., 2001).

Complications

Potential

complications of chronic renal failure that concern the nurse and that

necessitate a collaborative approach to care include the following:

· Hyperkalemia due to

decreased excretion, metabolic acido-sis, catabolism, and excessive intake

(diet, medications, fluids)

· Pericarditis,

pericardial effusion, and pericardial tamponade due to retention of uremic waste

products and inadequate dialysis

· Hypertension due to

sodium and water retention and mal-function of the

renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

· Anemia due to decreased

erythropoietin production, de-creased RBC life span, bleeding in the GI tract

from irritat-ing toxins, and blood loss during hemodialysis

· Bone disease and

metastatic calcifications due to retention of phosphorus, low serum calcium

levels, abnormal vitamin D metabolism, and elevated aluminum levels

Medical Management

The

goal of management is to maintain kidney function and homeostasis for as long

as possible. All factors that contribute to ESRD and all factors that are

reversible (eg, obstruction) are iden-tified and treated. Management is

accomplished primarily with medications and diet therapy, although dialysis may

also be needed to decrease the level of uremic waste products in the blood

(Fink et al., 2001).

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Complications

can be prevented or delayed by administering pre-scribed antihypertensives,

erythropoietin (Epogen), iron supple-ments, phosphate-binding agents, and

calcium supplements.

Antacids.

Hyperphosphatemia and

hypocalcemia are treatedwith aluminum-based antacids that bind dietary

phosphorus in the GI tract. However, concerns about the potential long-term toxicity of aluminum and

the association of high aluminum levels with neurologic symptoms and

osteomalacia have led some physi-cians to prescribe calcium carbonate in place

of high doses of aluminum-based antacids. This medication also binds dietary

phosphorus in the intestinal tract and permits the use of smaller doses of

antacids. Both calcium carbonate and phosphorus-binding antacids must be

administered with food to be effective. Magnesium-based antacids must be

avoided to prevent magnesium toxicity.

Antihypertensive and Cardiovascular Agents.

Hypertension ismanaged by intravascular volume control and a variety of

anti-hypertensive agents. Heart failure and pulmonary edema may also require

treatment with fluid restriction, low-sodium diets, diuretic agents, inotropic

agents such as digitalis or dobutamine, and dialysis. The metabolic acidosis of

chronic renal failure usu-ally produces no symptoms and requires no treatment;

however, sodium bicarbonate supplements or dialysis may be needed to correct the

acidosis if it causes symptoms (Tonelli et al., 2001).

Antiseizure Agents.

Neurologic

abnormalities may occur, so thepatient must be observed for early evidence of

slight twitching, headache, delirium, or seizure activity. If seizures occur,

the onset of the seizure is recorded along with the type, duration, and

gen-eral effect on the patient. The physician is notified immediately.

Intravenous diazepam (Valium) or phenytoin (Dilantin) is usu-ally administered

to control seizures. The side rails of the bed should be padded to protect the

patient.

Erythropoietin.

Anemia

associated with chronic renal failure istreated with recombinant human

erythropoietin (Epogen). Ane-mic patients (hematocrit less than 30%) present

with nonspecific symptoms, such as malaise, general fatigability, and decreased

ac-tivity tolerance. Epogen therapy is initiated to achieve a hemat-ocrit of

33% to 38%, which generally alleviates the symptoms of anemia. Epogen is

administered either intravenously or subcuta-neously three times a week. It may

take 2 to 6 weeks for the hemat-ocrit to rise; therefore, Epogen is not

indicated for patients who need immediate correction of severe anemia. Adverse

effects seen with Epogen therapy include hypertension (especially during early

stages of treatment), increased clotting of vascular access sites, seizures,

and depletion of body iron stores (Fink et al., 2001).

The

patient receiving Epogen may experience influenza-like symptoms with initiation

of therapy; these tend to subside with repeated doses. Management involves

adjustment of heparin to prevent clotting of the dialysis lines during

hemodialysis treat-ments, frequent monitoring of hematocrit, and periodic

assess-ment of serum iron and transferrin levels. Because adequate stores of

iron are necessary for an adequate response to erythropoietin, supplementary

iron may be prescribed. In addition, the patient’s blood pressure and serum

potassium level are monitored to detect hypertension and rising serum potassium

levels, which may occur with therapy and the increasing RBC mass. The

occurrence of hy-pertension requires initiation or adjustment of the patient’s

anti-hypertensive therapy. Hypertension that cannot be controlled is a

contraindication to recombinant erythropoietin therapy.

Patients

who have received Epogen have reported decreased levels of fatigue, an

increased feeling of well-being, better tolerance of dialysis, higher energy

levels, and improved exercise tolerance. Additionally, this therapy has

decreased the need for transfusion and its associated risks, including

bloodborne infectious disease, antibody formation, and iron overload (Fink et

al., 2001).

NUTRITIONAL THERAPY

Dietary

intervention is necessary with deterioration of renal func-tion and includes

careful regulation of protein intake, fluid intake to balance fluid losses,

sodium intake to balance sodium losses, and some restriction of potassium. At

the same time, adequate caloric intake and vitamin supplementation must be

ensured. Pro-tein is restricted because urea, uric acid, and organic acids—the

breakdown products of dietary and tissue proteins—accumulate rapidly in the

blood when there is impaired renal clearance. The allowed protein must be of

high biologic value (dairy prod-ucts, eggs, meats). High-biologic-value proteins

are those that are complete proteins and supply the essential amino acids

necessary for growth and cell repair.

Usually,

the fluid allowance is 500 to 600 mL more than the previous day’s 24-hour urine

output. Calories are supplied by car-bohydrates and fat to prevent wasting.

Vitamin supplementation is necessary because a protein-restricted diet does not

provide the necessary complement of vitamins. Additionally, the patient on

dialysis may lose water-soluble vitamins from the blood during the dialysis treatment.

OTHER THERAPY: DIALYSIS

Hyperkalemia

is usually prevented by ensuring adequate dialysis treatments with potassium

removal and careful monitoring of all medications, both oral and intravenous,

for their potassium con-tent. The patient is placed on a potassium-restricted

diet. Occa-sionally, Kayexalate, a cation-exchange resin, administered orally,

may be needed. The patient with increasing symptoms of chronic renal failure is

referred to a dialysis and transplantation center early in the course of

progressive renal disease. Dialysis is usually initiated when the patient

cannot maintain a reasonable lifestyle with conservative treatment.

Nursing Management

The

patient with chronic renal failure requires astute nursing care to avoid the

complications of reduced renal function and the stresses and anxieties of

dealing with a life-threatening illness. Ex-amples of potential nursing

diagnoses for these patients include the following:

· Excess fluid volume

related to decreased urine output, dietary excesses, and retention of sodium

and water

· Imbalanced nutrition:

less than body requirements related to anorexia, nausea and vomiting, dietary

restrictions, and altered oral mucous membranes

· Deficient knowledge

regarding condition and treatment regimen

· Activity intolerance

related to fatigue, anemia, retention of waste products, and dialysis procedure

· Low self-esteem related

to dependency, role changes, changes in body image, and sexual dysfunction

Nursing

care is directed toward assessing fluid status and iden-tifying potential

sources of imbalance, implementing a dietary program to ensure proper

nutritional intake within the limits of the treatment regimen, and promoting

positive feelings by en-couraging increased self-care and greater independence.

It is ex-tremely important to provide explanations and information to the

patient and family concerning ESRD, treatment options, and potential

complications. A great deal of emotional support is needed by the patient and

family because of the numerous changes experienced. Specific interventions,

along with rationale and evaluation criteria, are presented in more detail in

the Plan of Nursing Care.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care.

The nurse

plays an extremely im-portant role in teaching the patient with ESRD. Because

of the extensive teaching needed, the home care nurse, dialysis nurse, and

nurse in the outpatient setting all provide ongoing education and reinforcement

while monitoring the patient’s progress and compliance with the treatment

regimen.

A

nutritional referral and explanations of nutritional needs are helpful because

of the numerous dietary changes required. The patient is taught how to check

the vascular access device for pa-tency and how to take precautions, such as

avoiding venipunc-tures and blood pressure measurements on the arm with the

access device.

Additionally,

the patient and family require considerable as-sistance and support in dealing

with the need for dialysis and its long-term implications. For instance, they

need to know what problems to report to the health care provider, including the

following:

· Worsening signs and

symptoms of renal failure (nausea, vomiting, change in usual urine output [if

any], ammonia odor on breath)

· Signs and symptoms of hyperkalemia

(muscle weakness, diarrhea, abdominal cramps)

· Signs and symptoms of

access problems (clotted fistula or graft, infection)

These

signs and symptoms of decreasing renal function, in ad-dition to increasing BUN

and serum creatinine levels, may indi-cate a need to alter the dialysis

prescription. The dialysis nurses also provide ongoing education and support at

each treatment visit.

Continuing Care.

The

importance of follow-up examinationsand treatment is stressed to the patient

and family because of changing physical status, renal function, and dialysis

require-ments. Referral for home care provides the home care nurse with the

opportunity to assess the patient’s environment, emotional status, and the

coping strategies used by the patient and family to deal with the changes in

family roles often associated with chronic illness.

The

home care nurse also assesses the patient for further dete-rioration of renal

function and signs and symptoms of complica-tions resulting from the primary

renal disorder, the resulting renal failure, and effects of treatment

strategies (eg, dialysis, medica-tions, dietary restrictions). Many patients

need ongoing education and reinforcement on the multiple dietary restrictions

required, including fluid, sodium, potassium, and protein restriction.

Reminders about the need for health promotion activities and health screening

are an important part of nursing care for the patient with renal failure.

Gerontologic Considerations

Changes in kidney function with normal aging increase the sus-ceptibility of elderly patients to kidney dysfunction and renal fail-ure. Because alterations in renal blood flow, glomerular filtration, and renal clearance increase the risk for medication-associated changes in renal function, precautions are indicated with all medications.

This is because of the frequent use of multiple-prescription and

over-the-counter medications by elderly patients. The incidence of systemic

diseases, such as atherosclerosis, hyper-tension, heart failure, diabetes, and

cancer, increases with advanc-ing age, predisposing older adults to renal

disease associated with these disorders. Therefore, nurses in all settings need

to be alert for signs and symptoms of renal dysfunction in elderly patients.

With

age, the kidney is less able to respond to acute fluid and electrolyte changes.

Therefore, acute problems need to be pre-vented if possible or recognized and

treated quickly to avoid kid-ney damage. When the elderly patient must undergo

extensive diagnostic tests, or when new medications (eg, diuretic agents) are

added, precautions must be taken to prevent dehydration, which can compromise

marginal renal function and lead to ARF.

The

elderly patient may develop atypical and nonspecific signs and symptoms of

disturbed renal function and fluid and elec-trolyte imbalances. Recognition of

these problems is further ham-pered by their association with preexisting

disorders and the misconception that they are normal changes of aging.

ACUTE RENAL FAILURE IN OLDER ADULTS

The

incidence of ARF is increasing in older, hospitalized patients. About half of

patients who develop ARF during hospitalization for a medical or surgical

problem are older than 60 years of age. Evidence also demonstrates that ARF is

often seen in the com-munity setting. Nurses in the ambulatory setting need to

be cog-nizant of the risk for ARF in their elderly patients, especially those

undergoing diagnostic testing or procedures that can result in de-hydration.

The mortality rate is slightly higher for ARF in elderly patients than for

their younger counterparts.

The

etiology of ARF in older adults includes prerenal causes, such as dehydration,

and intrarenal causes, such as nephrotoxic agents (medications, contrast

agents). Diabetes mellitus increases the risk for contrast agent-induced renal

failure because of pre-existing renal insufficiency and the imposed fluid

restriction needed for many tests. Suppression of thirst, enforced bed rest,

lack of drinking water, and confusion all contribute to the older patient’s

failure to consume adequate fluids and may lead to dehydration and compromise

of already decreased renal function.

CHRONIC RENAL FAILURE IN OLDER ADULTS

Historically,

the age of patients developing ESRD steadily rose each year, but it appears to

have stabilized since 1993 at a mean age of 60 years. In the past, rapidly

progressive glomerulonephri-tis, membranous glomerulonephritis, and

nephrosclerosis were the most common causes of chronic renal failure in the

elderly. Today, however, diabetes mellitus and hypertension are the lead-ing

causes of chronic renal failure in the elderly (Bakris et al., 2000). Other

common causes of chronic renal failure in the el-derly population are

interstitial nephritis and urinary tract ob-struction. The signs and symptoms

of renal disease in the elderly are commonly nonspecific. The occurrence of

symptoms of other disorders (heart failure, dementia) can mask the symptoms of

renal disease and delay or prevent diagnosis and treatment. The patient often

develops signs and symptoms of nephrotic syn-drome, such as edema and

proteinuria.

Hemodialysis

and peritoneal dialysis have been used effec-tively in treating elderly

patients (Carey et al., 2001). Although there is no specific age limitation for

renal transplantation, con-comitant disorders (ie, coronary artery disease,

peripheral vascu-lar disease) have made it a less common treatment for the elderly.

The

outcome, however, is comparable to that of younger pa-tients. Some elderly

patients elect not to participate in these treatment strategies. Conservative

management, including nutri-tional therapy, fluid control, and medications,

such as phosphate binders, may be considered in patients who are not suitable

for or elect not to participate in dialysis or transplantation.

Related Topics