Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Female Reproductive Disorders

Fistulas of the Vagina - Structural Disorders

Structural Disorders

FISTULAS

OF THE VAGINA

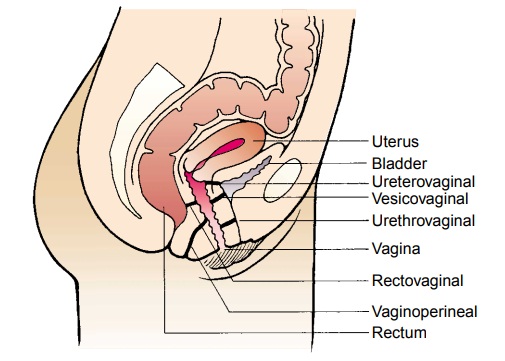

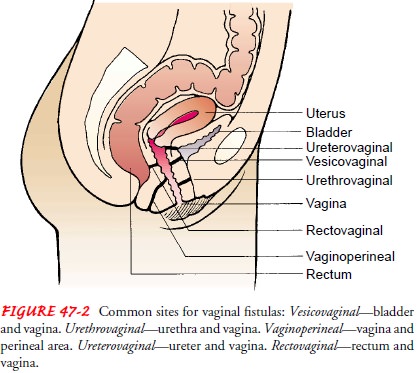

A fistula is an abnormal, tortuous

opening between two internal hollow organs or between an internal hollow organ

and the exte-rior of the body. The name of the fistula indicates the two areas

that are connected abnormally: a vesicovaginal fistula is an open-ing between

the bladder and the vagina, and a rectovaginal fistula is an opening between

the rectum and the vagina (Fig. 47-2). Fis-tulas may be congenital in origin.

In adults, however, breakdown usually occurs because of tissue damage resulting

from injury sus-tained during surgery, vaginal delivery, radiation therapy, or

dis-ease processes such as carcinoma.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms depend on the specific defect. For example, in the pa-tient with a vesicovaginal fistula, urine escapes continuously into the vagina. With a rectovaginal fistula, there is fecal incontinence, and flatus is discharged through the vagina. The combination of fecal discharge with leukorrhea results in malodor that is difficult to control.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

A

history of the symptoms experienced by the patient is impor-tant to identify

the structural alterations and to assess the impact of the symptoms on the

patient’s quality of life. In addition, the use of methylene blue dye helps

delineate the course of the fistula. In vesicovaginal fistula, the dye is

instilled into the bladder and appears in the vagina. After a negative

methylene blue test result, indigo carmine is injected intravenously; the

appearance of the dye in the vagina indicates a ureterovaginal fistula.

Cystoscopy or intravenous pyelography may then be used to determine the exact

location.

Medical Management

The

goal is to eliminate the fistula and to treat infection and ex-coriation. A

fistula may heal without surgical intervention, but surgery is often required.

If the primary care provider determines that a fistula will heal without

surgical intervention, care is planned to relieve discomfort, prevent infection,

and improve the patient’s self-concept and self-care abilities. Measures to

effect healing in-clude proper nutrition, cleansing douches and enemas, rest,

and administration of prescribed intestinal antibiotic agents. A recto-vaginal

fistula heals faster when the patient eats a low-residue diet and when the

affected tissue drains properly. Warm perineal irri-gations and controlled

heat-lamp treatments promote healing.

Sometimes

a fistula does not heal on its own and cannot be surgically repaired. In this

situation care must be planned and implemented on an individual basis.

Cleanliness, frequent sitz baths, and deodorizing douches are required, as are

perineal pads and protective undergarments. Meticulous skin care is nec-essary

to prevent excoriation. Applying bland creams or lightly dusting with

cornstarch may be soothing. Additionally, attend-ing to the patient’s social

and psychological needs is an essential aspect of care.

If the

patient will have a fistula repaired surgically, preopera-tive treatment of any

existing vaginitis is important to ensure suc-cess. Usually, the vaginal

approach is used to repair vesicovaginal and urethrovaginal fistulas; the

abdominal approach is used to re-pair fistulas that are large or complex.

Fistulas that are difficult to repair or that are very large may require

surgical repair with a uri-nary or fecal diversion.

Because

fistulas usually are related to obstetric, surgical, or radi-ation trauma,

occurrence in a patient without previous vaginal delivery or a history of

surgery must be evaluated carefully. Crohn’s disease or lymphogranuloma

venereum may be the cause.

Despite

the best surgical intervention, fistulas may recur. After surgery, medical

follow-up continues for at least 2 years to mon-itor for a possible recurrence.

Related Topics