Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Antihypertensive Agents

Drugs that Alter Sodium & Water Balance

DRUGS THAT ALTER SODIUM &

WATER BALANCE

Dietary

sodium restriction has been known for many years to decrease blood pressure in

hypertensive patients. With the advent of diuretics, sodium restriction was

thought to be less important. However, there is now general agreement that

dietary control of blood pressure is a relatively nontoxic therapeutic measure

and may even be preventive. Even modest dietary sodium restriction lowers blood

pressure (though to varying extents) in many hypertensive persons.

Mechanisms of Action & Hemodynamic

Effects of Diuretics

Diuretics

lower blood pressure primarily by depleting body sodium stores. Initially,

diuretics reduce blood pressure by reducing blood volume and cardiac output;

peripheral vascular resistance may increase. After 6–8 weeks, cardiac output

returns toward normal while peripheral vascular resistance declines. Sodium is

believed to contribute to vascular resistance by increasing vessel stiffness

and neural reactivity, possibly related to altered sodium-calcium exchange with

a resultant increase in intracellular calcium. These effects are reversed by diuretics

or sodium restriction.

Diuretics

are effective in lowering blood pressure by 10–15 mm Hg in most patients, and

diuretics alone often provide adequate treat-ment for mild or moderate

essential hypertension. In more severe hypertension, diuretics are used in

combination with sympathople-gic and vasodilator drugs to control the tendency

toward sodium retention caused by these agents. Vascular responsiveness—ie, the

ability to either constrict or dilate—is diminished by sympathople-gic and

vasodilator drugs, so that the vasculature behaves like an inflexible tube. As

a consequence, blood pressure becomes exqui-sitely sensitive to blood volume.

Thus, in severe hypertension, when multiple drugs are used, blood pressure may

be well controlledwhen blood volume is 95% of normal but much too high when

blood volume is 105% of normal.

Use of Diuretics

Thiazide

diuretics are appropriate for most patients with mild or moderate hypertension

and normal renal and cardiac function. More power-ful diuretics (eg, those

acting on the loop of Henle) such as furo-semide are necessary in severe hypertension,

when multiple drugs with sodium-retaining properties are used; in renal

insufficiency, when glomerular filtration rate is less than 30 or 40 mL/min;

and in cardiac failure or cirrhosis, in which sodium retention is

marked.Potassium-sparing diuretics are useful both to avoid excessive potassium

depletion and to enhance the natriuretic effects of other diuretics.

Aldosterone receptor antagonists in particular also have a favorable effect on

cardiac function in people with heart failure.Some pharmacokinetic

characteristics and the initial and usual maintenance dosages of

hydrochlorothiazide are listed in Table 11–2. Although thiazide diuretics are

more natriuretic at higher doses (up to 100–200 mg of hydrochlorothiazide),

when used as a single agent, lower doses (25–50 mg) exert as much

anti-hypertensive effect as do higher doses. In contrast to thiazides, the

blood pressure response to loop diuretics continues to increase at doses many

times greater than the usual therapeutic dose.

Toxicity of Diuretics

In

the treatment of hypertension, the most common adverse effect of diuretics

(except for potassium-sparing diuretics) is potassium depletion. Although mild

degrees of hypokalemia are tolerated well by many patients, hypokalemia may be

hazardous in persons taking digitalis, those who have chronic arrhythmias, or

those with acute myocardial infarction or left ventricular dysfunction.

Potassium loss is coupled to reabsorption of sodium, and restriction of dietary

sodium intake therefore minimizes potassium loss. Diuretics may also cause

magnesium depletion, impair glucose tolerance, and increase serum lipid

concentrations. Diuretics increase uric acid concentrations and may precipitate

gout. The use of low doses minimizes these adverse metabolic effects without

impairing the antihypertensive action. Potassium-sparing diuretics may

producehyperkalemia, particularly in patients with renal insufficiency and

those taking ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers; spironolactone (a

steroid) is associated with gynecomastia.

Resistant Hypertension & Polypharmacy

Monotherapy of hypertension (treatment with a single drug) is desirable because compliance is likely to be better and cost is lower, and because in some cases adverse effects are fewer. However, most patients with hypertension require two or more drugs, preferably acting by different mechanisms (polyphar-macy). According to some estimates, up to 40% of patients may respond inadequately even to two agents and are considered to have “resistant hypertension.” Some of these patients have treat-able secondary hypertension that has been missed, but most do not and three or more drugs are required.

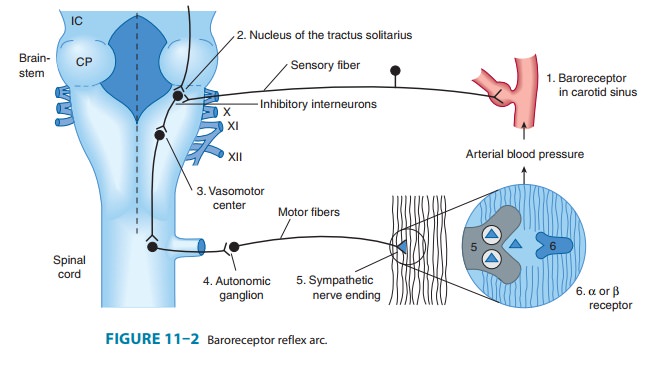

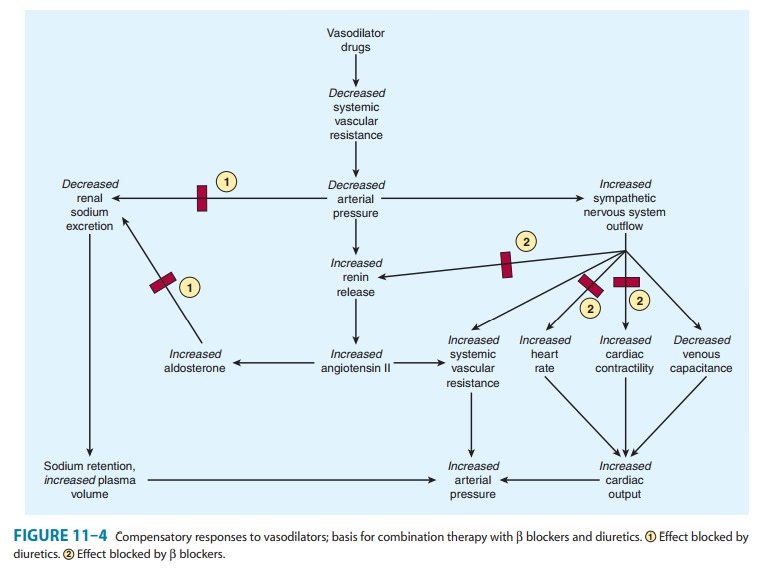

One rationale for polypharmacy in hypertension is that most drugs evoke compensatory regulatory mechanisms for maintain-ing blood pressure (see Figures 6–7 and 11–1), which may mark-edly limit their effect. For example, vasodilators such as hydralazine cause a significant decrease in peripheral vascular resistance, but evoke a strong compensatory tachycardia and salt and water retention (Figure 11–4) that is capable of almost completely reversing their effect. The addition of a β blocker prevents the tachycardia; addition of a diuretic (eg, hydrochloro-thiazide) prevents the salt and water retention. In effect, all three drugs increase the sensitivity of the cardiovascular system to each other’s actions.

A second reason is that some drugs have only modest maxi-mum efficacy but reduction of long-term morbidity mandatestheir use. Many studies of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors report a maximal lowering of blood pressure of less than 10 mm Hg. In patients with stage 2 hypertension (pressure 160/100 mm Hg), this is inadequate to prevent all the sequelae of hypertension, but ACE inhibitors have important long-term benefits in preventing or reducing renal disease in diabetic per-sons, and reduction of heart failure Finally, the toxicity of some effective drugs prevents their use at maximally effective dosage. The widespread indiscrimi-nate use of β blockers has been criticized because several large clinical trials indicate that some members of the group, eg, metoprolol and carvedilol, have a greater benefit than others, eg, atenolol. However, all β blockers appear to have similar ben-efits in reducing mortality after myocardial infarction, so these drugs are particularly indicated in patients with an infarct and hypertension.

In practice, when hypertension does not respond adequately to a regimen of one drug, a second drug from a different class with a different mechanism of action and different pattern of toxicity is added. If the response is still inadequate and compli-ance is known to be good, a third drug should be added. If three drugs (usually including a diuretic) are inadequate, dietary sodium restriction and an additional drug may be necessary

Related Topics