Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Antihypertensive Agents

Adrenergic Neuron-Blocking Agents

ADRENERGIC NEURON-BLOCKING AGENTS

These

drugs lower blood pressure by preventing normal physio-logic release of

norepinephrine from postganglionic sympathetic neurons.

Guanethidine

In

high enough doses, guanethidine can produce profound sym-pathoplegia. The resulting

high maximal efficacy of this agent made it the mainstay of outpatient therapy

of severe hypertension for many years. For the same reason, guanethidine can

produce all of the tox-icities expected from “pharmacologic sympathectomy,”

including marked postural hypotension, diarrhea, and impaired ejaculation.

Because of these adverse effects, guanethidine is now rarely used.

Guanethidine

is too polar to enter the central nervous system.

Guanadrel is a guanethidine-like drug that is available

in the USA. Bethanidine and debrisoquin, antihypertensive agents

not available for clinical use in the USA, are similar.

A. Mechanism and Sites of Action

Guanethidine

inhibits the release of norepinephrine from sympa-thetic nerve endings (see

Figure 6–4). This effect is probably responsible for most of the sympathoplegia

that occurs in patients. Guanethidine is transported across the sympathetic

nerve mem-brane by the same mechanism that transports norepinephrine itself

(NET, uptake 1), and uptake is essential for the drug’s action. Once

guanethidine has entered the nerve, it is concentrated in transmitter vesicles,

where it replaces norepinephrine. Because it replaces norepinephrine, the drug

causes a gradual depletion of norepinephrine stores in the nerve ending.

Because

neuronal uptake is necessary for the hypotensive activ-ity of guanethidine,

drugs that block the catecholamine uptake process or displace amines from the

nerve terminal block its effects. These

include cocaine, amphetamine, tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, and

phenoxybenzamine.

B. Pharmacokinetics and Dosage

Because

of guanethidine’s long half-life (5 days), the onset of sym-pathoplegia is

gradual (maximal effect in 1–2 weeks), and sym-pathoplegia persists for a

comparable period after cessation of therapy. The dose should not ordinarily be

increased at intervals shorter than 2 weeks.

C. Toxicity

Therapeutic

use of guanethidine is often associated with symp-tomatic postural hypotension

and hypotension following exercise, particularly when the drug is given in high

doses. Guanethidine-induced sympathoplegia in men may be associated with

delayed or retrograde ejaculation (into the bladder). Guanethidine com-monly

causes diarrhea, which results from increased gastrointesti-nal motility due to

parasympathetic predominance in controlling the activity of intestinal smooth

muscle.

Interactions

with other drugs may complicate guanethidine therapy. Sympathomimetic agents,

at doses available in over-the-counter cold preparations, can produce

hypertension in patients taking guanethidine. Similarly, guanethidine can

produce hyper-tensive crisis by releasing catecholamines in patients with

pheo-chromocytoma. When tricyclic antidepressants are administered to patients

taking guanethidine, the drug’s antihypertensive effect is attenuated, and

severe hypertension may follow.

Reserpine

Reserpine,

an alkaloid extracted from the roots of an Indian plant, Rauwolfia serpentina, was one of the first effective drugs used on

alarge scale in the treatment of hypertension. At present, it is rarely used

owing to its adverse effects.

A. Mechanism and Sites of Action

Reserpine

blocks the ability of aminergic transmitter vesicles to take up and store

biogenic amines, probably by interfering with the vesicular membrane-associated

transporter (VMAT, see Figure 6–4). This effect occurs throughout the body,

resulting in depletion of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin in both

central and peripheral neurons. Chromaffin granules of the adrenal medulla are

also depleted of catecholamines, although to a lesser extent than are the

vesicles of neurons. Reserpine’s effects on adrenergic vesicles appear

irreversible; trace amounts of the drug remain bound to vesicular membranes for

many days.

Depletion

of peripheral amines probably accounts for much of the beneficial

antihypertensive effect of reserpine, but a central component cannot be ruled

out. Reserpine readily enters the brain, and depletion of cerebral amine stores

causes sedation, mental depression, and parkinsonism symptoms.

At

lower doses used for treatment of mild hypertension, reser-pine lowers blood

pressure by a combination of decreased cardiac output and decreased peripheral

vascular resistance.

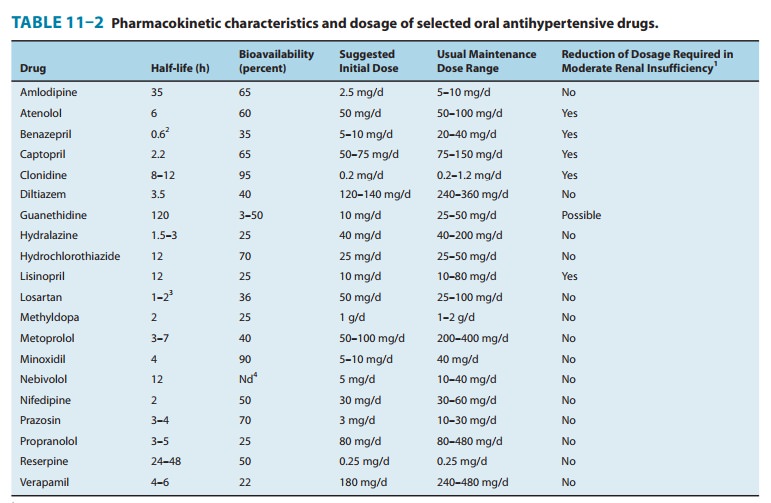

Pharmacokinetics and Dosage

Toxicity

At

the low doses usually administered, reserpine produces little postural

hypotension. Most of the unwanted effects of reserpine result from actions on

the brain or gastrointestinal tract. High doses of reserpine characteristically

produce sedation, lassitude, nightmares, and severe mental depression;

occasionally, these occur even in patients receiving low doses (0.25 mg/d).

Much less frequently, ordinary low doses of reserpine produce extrapyramidal

effects resembling Parkinson’s disease, probably as a result of dopamine

depletion in the corpus striatum. Although these central effects are uncommon,

it should be stressed that they may occur at any time, even after months of

uneventful treatment. Patients with a history of mental depression should not

receive reserpine, and the drug should be stopped if depres-sion

appears.Reserpine rather often produces mild diarrhea and gastrointes-tinal

cramps and increases gastric acid secretion. The drug should not be given to

patients with a history of peptic ulcer.

Related Topics