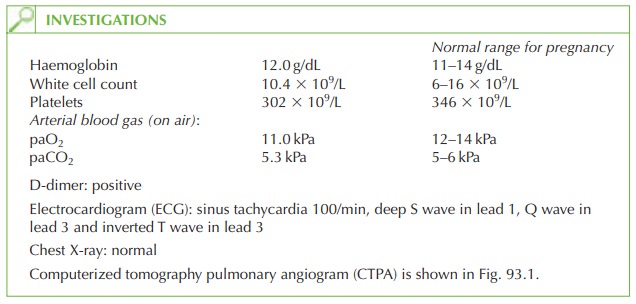

Chapter: Case Study in Obstetrics and Gynaecology: Peripartum Care and Obstetric Emergencies

Case Study Reports: Breathlessness in Pregnancy

History

A 42-year-old woman is referred

by her general practitioner with breathlessness for the past 3 days. She is 34 weeks pregnant

in her third pregnancy. Prior to this she has had an emer- gency Caesarean section for abnormal cardiotocograph in labour,

followed by a 7-week miscarriage.

In this pregnancy she was seen

by the obstetric consultant to discuss

plans for delivery, and is hoping for a vaginal

delivery. Ultrasound scans

and blood tests

have been normal. Her booking blood pressure was

138/80 mmHg and has remained stable during the pregnancy.

She describes her shortness of breath starting

while she was at work and slightly

worsen- ing since. She felt particularly breathless when she ran to catch a bus on her way home

yesterday. She has some left-sided chest pain on breathing in. There is no cough

or haemoptysis. She has

had no previous episodes. She has

not noticed any

calf pain but

has left leg swelling and some back pain.

Examination

The body mass

index is 28 kg/m2. The

woman does not

look obviously unwell.

Blood pre- ssure is 127/78 mmHg

and heart rate

98/min. Oxygen saturation is 96 per

cent on air.

On examination of the chest there

is a systolic murmur and no added

sounds. Chest expan- sion is normal but

the woman reports

pain on taking

a deep breath.

The chest is resonant

to percussion and

chest sounds are

normal except for

a pleural rub

on the left.

The left leg is

generally swollen but no redness

or tenderness is apparent.

Questions

·

What is the diagnosis?

·

What further imaging is required?

·

How

would you manage

this woman in the immediate term, during delivery

and postnatally?

ANSWER

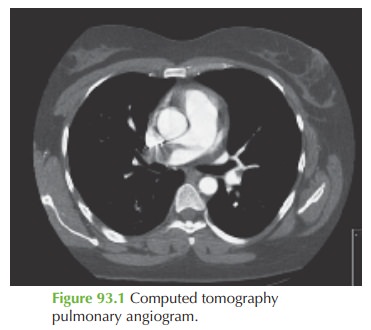

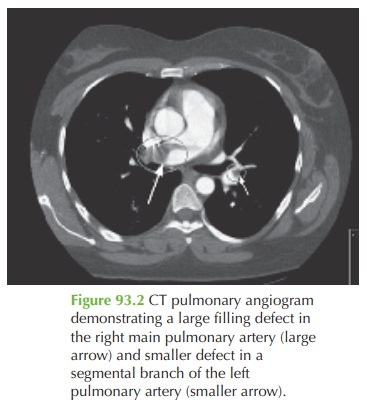

The diagnosis is of pulmonary

embolism (PE). The shortness and breath and pleuritic chest pain are classic features, and the

ECG and blood gas analysis support the diagnosis. D-dimer is commonly raised in

pregnancy but also supports the diagnosis. The CTPA demonstrates a large

filling defect within

the right pulmonary artery and a smaller filling defect in the left segmental

pulmonary artery, consistent with blood clots

(pulmonary embolism). These findings

are illustrated by the arrows

in Fig. 93.2.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE)

is the leading cause of direct deaths

in the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health,

accounting for death

in 1.2 per

100 000 mater- nities. Non-fatal VTE occurs in approximately 60 in 10 000 pregnancies, and there may be

many more unrecognized cases. Pregnancy itself is a risk factor

because of the hyper-

oestrogenic state, the

altered blood viscosity and obstruction to venous blood

flow by the gravid uterus.

Further imaging

There is no clinical evidence of calf ileofemoral deep vein thrombosis, but generalized leg swelling and back pain

are suspicious of an ileofemoral thrombosis. If this

is confirmed, which may require Doppler

ultrasound or magnetic

resonance imaging (or if she develops

recurrent PE despite anticoagulation), then liaison with a vascular

team should be consid-

ered regarding the possibility of insertion of a vena caval filter.

Management

As with non-pregnant patients, anticoagulation is the mainstay

of treatment. Warfarin

is contraindicated in the first trimester of pregnancy but may safely

be given from 12 to 36

weeks. However it can cause difficulties with excessive bleeding

if it is not stopped

early enough before delivery

and it can be difficult

to achieve stable international normalized ratio levels. Therefore low-molecular-weight heparin

has become the treatment of choice

in pregnancy as it is simple to administer, relatively easy to reverse

in the emergency situ-

ation, does not require monitoring, and is safe.

At delivery the heparin should

ideally be discontinued 12 h before

delivery and recom- menced immediately following

delivery. Similarly an epidural or spinal anaesthetic should not be administered immediately after a heparin

dose.

Postnatally some women

change to warfarin, which is now known to be safe with breast- feeding, while others continue

low-molecular-weight heparin.

A large proportion of VTE occurs

postnatally, so anticoagulation should be continued for 6 weeks to 3 months

in the puerperium.

Graduated elastic compression stocking should be worn from the time of diagnosis until at least 6 weeks following delivery, to reduce

the risk of the post-thrombotic syndrome (chronic leg pain, swelling and ulceration).

Postnatal investigation for

inherited (e.g. protein C or S deficiency) or acquired

(e.g. anti- phospholipid

syndrome) thrombophilia is appropriate,

as is anticoagulation throughout any

subsequent pregnancy.

Related Topics