Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease

Mitral Regurgitation

MITRAL REGURGITATION

Preoperative Considerations

Mitral regurgitation can develop acutely

or insidiously as a result of a large number of disorders. Chronic mitral

regurgitation is usually the result of rheumatic fever (often with concomitant

mitral stenosis); con-genital or developmental abnormalities of the valve

apparatus; or dilatation, destruction, or calcification of the mitral annulus.

Acute mitral regurgitation is usually due to myocardial ischemia or infarction

(papillary muscle dysfunction or rupture of a chorda tendinea), infective

endocarditis, or chest trauma.

Pathophysiology

The principal derangement is a reduction

in forward stroke volume due to backward flow of blood into the left atrium

during systole. The left ventricle compen-sates by dilating and increasing

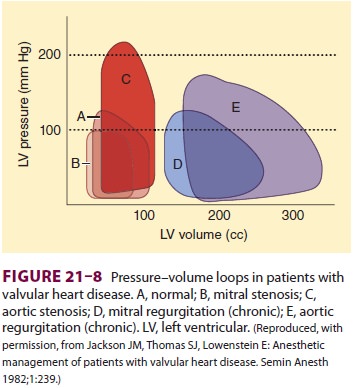

end-diastolic volume (Figure 21–8). Regurgitation thorugh the mitral valve

initially maintains a normal end systolic volume in spite of an increased end

diastolic volume. However, as the disease progresses the end systolic volume

increases. By increasing end-diastolic volume, the volume-overloaded left

ventricle can maintain a normal cardiac output despite blood being ejected

retrograde into the atrium. With time, patients with chronic mitral

regurgitation eventually develop eccentric left ventricular hypertrophy and

progres-sive impairment in contractility. In patients with severe mitral

regurgitation, the regurgitant volume may exceed the forward stroke volume. In

time, wall stress increases, resulting in an increased demand for myocardial

oxygen supply.

The regurgitant volume passing through

the mitral valve is dependent on the size of the mitral valve orifice (which

can vary with ventricular cav-ity size), the heart rate (systolic time), and

the left ventricular–left atrial pressure gradient during systole. The last

factor is af fected by the relative resistances of the two outflow paths from

the left ventricle, namely, SVR and left atrial compliance. Thus, a decrease in

SVR or an increase in mean left atrial pressure will reduce the regurgitant

volume. Atrial compliance also determines the predomi-nant clinical manifestations.

Patients with normal or reduced atrial compliance (acute mitral regurgita-tion)

have primarily pulmonary vascular congestion and edema. Patients with increased

atrial compli-ance (long-standing mitral regurgitation resulting in a large

dilated left atrium) primarily show signs of a reduced cardiac output. Most

patients are between the two extremes and exhibit symptoms of both pul-monary

congestion and low cardiac output. Patients with a regurgitant fraction of less

than 30% of the total stroke volume generally have mild symptoms. Regurgitant

fractions of 30% to 60% generally cause

moderate symptoms, whereas fractions

greater than 60% are associated with severe disease.Echocardiography,

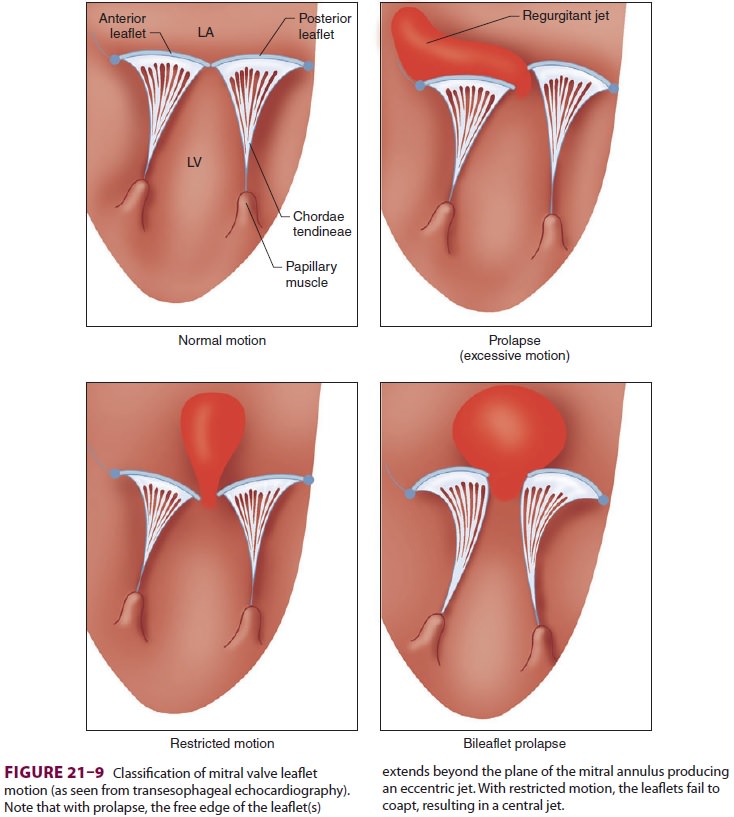

particularly TEE, is useful in delineating the underlying pathophysiology of

mitral regurgitation and guiding treatment. Mitral valve leaflet motion is

often described as normal, prolaps-ing, or restrictive (Figure 21–9). Excessive motion

or prolapse is defined by systolic movement of a leaflet beyond the plane of

the mitral valve and into the left atrium.

Calculating Regurgitant Fraction

To calculate regurgitant fraction (RF),

forward stroke volume (SV) and the regurgitant stroke vol-ume (RSV) must be

measured. Although they can both be estimated by catheterization data, pulsed

Doppler echocardiography provides reasonably acute calculations. Stroke volume

is measured at the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) and at the mitral

valve (MV), where

Stroke volume = cross-sectional area (A) × (TVI) and cross-sectional area (A) can be approximated as,

A = 0.785 × (diameter)2

The time–velocity integral (TVI) is the

integral of the velocity versus the time signal obtained with pulsed Doppler.

The TVI reflects the distance the blood has traveled during a heart beat. By

knowing the area through which the blood travels and the distance traveled, it

is possible to estimate the stroke volume. This is the case because the area is

expressed in centimeters squared, and the distance is expressed in centimeters.

The product of these measures is cubic centimeters or milliliters—hence, the

stroke volume for each heartbeat.

Thus, the volume of blood that enters

through the mitral valve must be the same as that passing through the left

ventricular outflow track. Any dif-ference between the two represents the

amount of the volume that initially entered the left ventricle, but that did

not pass the LVOT. This is the volume that regurgitated into the left atrium.

RSVmitral regurgitation =(AMV ×VTIMV)− (ALVOT

× TVILVOT),

and

RF = RSV/SV

An RSV greater than 65 mL usually

correlates with severe mitral regurgitation.

Treatment

Afterload reduction is beneficial in

most patients and may even be lifesaving in patients with acute mitral

regurgitation. Reduction of SVR increases forward SV and decreases the

regurgitant volume. Surgical treatment is usually reserved for patients with

moderate to severe symptoms. Valvuloplasty or valve repair are performed

whenever possible to avoid the problems associated with valve replace-ment (eg,

thromboembolism, hemorrhage, and prosthetic failure). Catheter-mediated valve

repairs are continually being refined, potentially reduc-ing the need for

“open” surgery. Anesthesiologists skilled in advanced perioperative

echocardiogra-phy assist in correctly identifying the leaflet(s) to be repaired

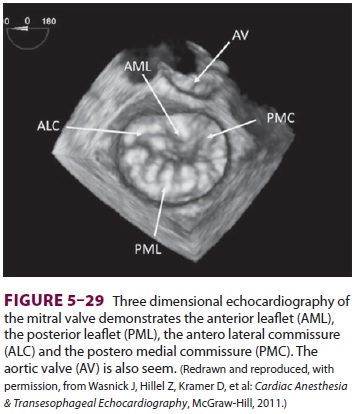

and determining the repair’s success. Three-dimensional echocardiography is

increas-ingly employed to assist in the assessment of the mitral valve (see

Figure 5-29).

Anesthetic Management

A. Objectives

Anesthetic management should be tailored

to the severity of mitral regurgitation as well asthe underlying left

ventricular function. Factors that exacerbate the regurgitation, such as slow

heart rates and acute increases in afterload, should be avoided. Bradycardia

can increase the regurgitant volume by increasing left ventricular

end-diastolic volume and acutely dilating the mitral annulus. The heart rate

should ideally be kept between 80 and 100 beats/min. Acute increases in left

ventricular afterload, such as with endotracheal intubation and surgical

stimula-tion under “light” anesthesia, should be treated rap-idly but without

excessive myocardial depression. Excessive volume expansion can also worsen the

regurgitation by dilating the left ventricle.

B. Monitoring

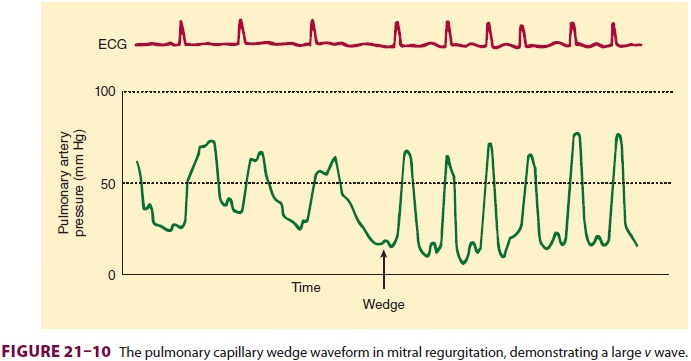

Monitors are based on the severity of

ventricular dysfunction, as well as the procedure. Mitral regur-gitation may be

recognized on the pulmonary artery wedge waveform as a large v wave and a rapid y descent (Figure 21–10). The height of the v wave is inversely related to atrial

and pulmonary vascular compliance, but is directly proportional to pulmo-nary

blood flow and the regurgitant volume; thus, the v wave may not be prominent in patients with chronic mitral

regurgitation, except during acute deterioration. Very large v waves are often apparent on the

pulmonary artery pressure waveform, even without wedging the catheter.

Color-flow Doppler TEE can be invaluable in quantitating the severity of

the regurgitation and guiding

therapeutic interven-tions in patients with severe mitral regurgitation. By

definition, blood flow reverses in the pulmonary veins during systole with

severe mitral regurgitation.

C. Choice of Agents

Patients with relatively well-preserved

ventricular function tend to do well with most anesthetic tech-niques. Spinal

and epidural anesthesia are well toler-ated, provided bradycardia is avoided.

Patients with moderate to severe ventricular impairment may be sensitive to

depression from high concentrations of volatile agents. An opioid-based

anesthetic may be more suitable for those patients—again, provided bradycardia

is avoided.

Related Topics