Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease

Congenital Heart Disease

Congenital Heart Disease

Preoperative Considerations

Congenital heart disease encompasses a

seemingly endless list of abnormalities that may be detected in infancy, early

childhood, or, less commonly, adult-hood. The incidence of congenital heart

disease in all live births approaches 1%. The natural history of some defects

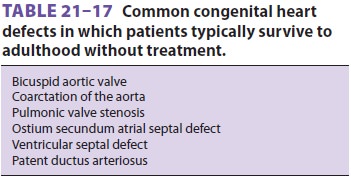

is such that patients often survive to adulthood ( Table 21–17). Moreover, the

number of surviving adults with congenital heart disease is steadily

increasing, possibly as a result of advances in surgical and medical treatment.

An increasing number of patients with congenital heart disease may therefore be

encountered during noncardiac surgery and obstetric deliveries. Knowledge of

the

anatomy of the original heart structure

defect and of any corrective repairs is essential prior to anesthetiz-ing the

patient with congental heart disease (CHD).

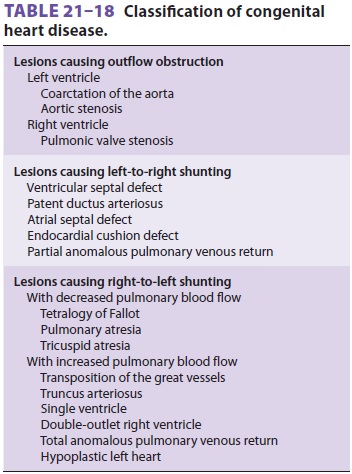

The complex nature and varying

pathophysiol-ogy of congenital heart defects make classification difficult. A

commonly used scheme is presented in Table 21–18. Most patients present with

cyano-sis, congestive heart failure, or an asymptomatic abnormality. Cyanosis

is typically the result of an abnormal intracardiac communication that allows

unoxygenated blood to reach the systemic arterial circulation (right-to-left

shunting). Congestive heart failure is most prominent with defects that either

obstruct left ventricular outflow or mark-edly increase pulmonary blood flow.

The latter is usually due to an abnormal intracardiac commu-nication that

returns oxygenated blood to the right heart (left-to-right shunting). Whereas

right-to-left shunts generally decrease pulmonary blood flow, some complex

lesions increase pulmonary blood flow—even in the presence of right-to-left

shunt-ing. In many cases, more than one lesion is present.

In fact, survival (prior to surgical

correction) with some anomalies (eg, transposition, total anoma-lous venous

return, pulmonary atresia) depends on the simultaneous presence of another

shunting lesion (eg, patent ductus arteriosus, patent foramen ovale,

ventricular septal defect). Chronic hypox-emia in patients with cyanotic heart

disease typi-cally results in erythrocytosis. This increase in red cell mass,

which is due to enhanced erythropoietin secretion from the kidneys, serves to

restore tissue oxygen concentration to normal. Unfortunately, blood viscosity

can also rise to the point at which it may interfere with oxygen delivery. When

tissue oxygenation is restored to normal, the hematocrit is stable (usually <65%), and symptoms of the hyper-viscosity syndrome

are absent, the patient is said to have compensated erythrocytosis. Patients

with uncompensated erythrocytosis do not establish this equilibrium; they have

symptoms of hypervis-cosity and may be at risk of thrombotic complica-tions,

particularly stroke. The last is aggravated by dehydration. Children younger

than age 4 years seem to be at greatest risk of stroke. Phlebotomy is generally

not recommended if symptoms of hyper-viscosity are absent and the hematocrit is

<65%.

Coagulation abnormalities are common in

patients with cyanotic heart disease. Platelet counts tend to be low-normal,

and many patients have subtle or overt defects in the coagulation cascade.

Phlebotomy may improve hemostasis in some patients. Hyperuricemia often occurs

because of increased urate reabsorption secondary to renal hypoperfusion. Gouty

arthritis is uncommon, but the hyperuricemia can result in progressive renal

impairment.

Preoperative Doppler echocardiography is

invaluable in helping to define the anatomy of the defect(s) and to confirm or

exclude the existence of other lesions or complications, their physiologi-cal

significance, and the effects of any therapeutic interventions.

Anesthetic Management

Th is population of patients includes four

groups: those who have undergone corrective cardiac sur-gery and require no

further operations, those who have had only palliative surgery, those who have

not yet undergone any cardiac surgery, and those whose conditions are

inoperable and may be awaiting car-diac transplantation. Although the

management of the first group of patients may be the same as that of normal

patients (except for consideration of prophy-lactic antibiotic therapy), the

care of others requires familiarity with the complex pathophysiology of these

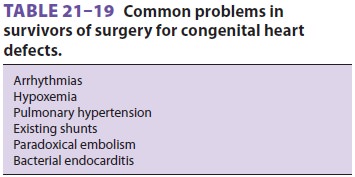

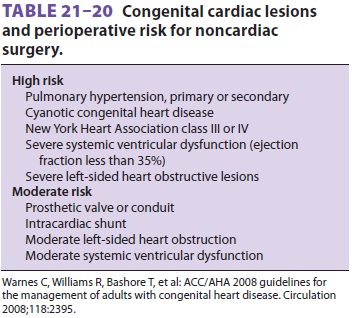

defects. Even patients who have had corrective surgery may be prone to the

development of periop-erative problems (Tables 21–19 and 21–20). Some surgical procedures

eliminate the risk of endocar-ditis, whereas others increase the risk through

the use of prosthetic valves or conduits or the creation of new shunts.

For the purpose of anesthetic

management, con-genital heart defects may be divided into obstructive lesions,

predominantly left-to-right shunts, or pre-dominantly right-to-left shunts. In

reality, shunts can also be bidirectional and may reverse under cer-tain

conditions.

Related Topics