Chapter: Psychology: Language

The Sensitive Period Hypothesis

The Sensitive

Period Hypothesis

The human brain continues to grow

and develop in the years after birth, reaching its mature state more or less at

the age of puberty, with some further brain development— especially in the

prefrontal cortex—continuing well into adolescence. If language is indeed

rooted in brain function, then we might expect language learning to be

influenced by these maturational changes. Is it? According to the sensitive period hypothesis, the brain

of the young child is particularly well suited to the task of language

learning. As the brain matures, learning (both of a first language and of later

languages) becomes more difficult (Lenneberg, 1967; Newport, 1990).

Sensitive periods for the uptake

and consolidation of new information seem to govern some aspects of learning in

many species. One example is the attachment of the

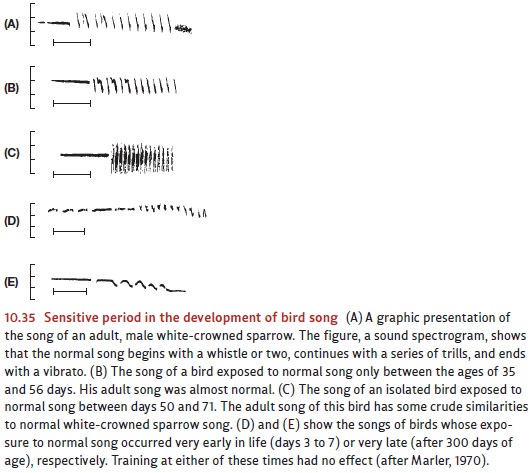

young of various animals to their mothers, which generally can be formed only in early childhood . Another example is bird song. Male birds of many species have a song that is characteristic of their own kind. They learn this song by listening to adult males of their species. But this exposure will be effective primarily when it occurs at a certain period in the bird’s life. To take a concrete case, baby white-crowned spar-rows will learn their species song in all its glory, complete with trills and grace notes, only if they hear this music (sung, of course, by an adult white-crowned sparrow) some-time between the 7th and 60th day of their life. If they do not hear the song during this period, but instead hear it sometime during the next month, they acquire only the rudi-ments of the song, without the full elaborations heard in normal adults (Figure 10.35).

If the exposure comes still

later, it has almost no effect. The bird will never sing nor-mally (Marler,

1970).

Do human languages work in the

same way? Are adults less able to learn language because they have passed

beyond some sensitive learning period? Much of the evidence has traditionally

come from studies of second-language learning.

SECOND – LANGUAGE LEARNING

In the initial stages of learning

a second language, adults appear to be much more effi-cient than children (Snow

& Hoefnagel-Hohle, 1978). The adult will venture halting but comprehensible

sentences soon after arrival in the new language community while the 2-year-old

may at first lapse into silence. But in the long run the outcome is just the

reverse. After a few years, very small children speak the new language fluently

and soon sound just like natives. This is much less common in adults. This

point has been docu-mented in many studies. In one investigation, the participants

in the experiments were native Chinese and Korean speakers who came to the

United States (and became immersed in the English-language community) at

varying ages. These individuals were tested only after they had been in the

United States for at least 5 years, so they had had ample exposure to English.

And all of them were students and faculty members at a large midwestern

university, so they shared some social background (and presumably were

motivated to learn the new language so as to succeed in their university

roles).

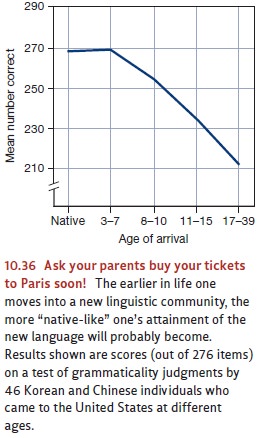

In the test procedure, half of

the sentences the participants heard were grossly ungrammatical (e.g., The farmer bought two pig at the market; The

little boy is speak to apoliceman). The other half were the grammatical

counterparts of these same sentences.The participants’ task was to indicate

which sentences were grammatical in English and which were not. The results are

shown in Figure 10.36. Those who had been exposed to English before age seven

performed just like native speakers of English. Thereafter there was an

increasing decrement in performance as a function of age at first exposure. The

older the subjects when they first came to the United States, the less well

they acquired English (J. Johnson & Newport, 1989).

Recent experimentation confirms

that very young children acquire second languages at native levels, and adds

important detail about this process. Snedeker, Geren, and Shafto (2007)

followed the language learning progress of Chinese children adopted (at ages 2

to 6 years) by Americans. After adoption, these children were immersed in

monolingual English-language environments. Their English-language learning was

compared with that of American-born infants. Would the older Chinese-born

children learn differently (because they were more cognitively mature)? Or

would they learn in the same way as the infants (because all of them were

learning English from scratch)? The results show both effects: Just like infant

first-language learners, the adoptees learned nouns before verbs, and content

words before function words, suggesting that such words are easiest to learn

regardless of cognitive status of the learner. But the adoptees acquired

vocabulary at a faster rate, and so caught up to native-born age-mates after 18

months or so of being in the new language community Finally, we can ask how the

native and later-learned languages are distributed in the brain. It could be,

for example, that the usual brain locus for language gets set up pre-cisely in

the course of acquiring a first language and thereafter loses plasticity; as a

result, the later-learned language must be shunted into new areas that are not

special-ized for, or are secondary for, language. This would be another way of

explaining why knowledge of the first language is generally so much better than

knowledge of the sec-ond or third or fourth language learned. There is in fact

accumulating evidence that the brain loci of late-learned languages usually are

different from those of the first-learnedIf the exposure comes still later, it

has almost no effect. The bird will never sing nor-mally (Marler, 1970).

Do human languages work in the

same way? Are adults less able to learn language because they have passed

beyond some sensitive learning period? Much of the evidence has traditionally

come from studies of second-language learning.

SECOND - LANGU AGE LEARNING

In the initial stages of learning

a second language, adults appear to be much more effi-cient than children (Snow

& Hoefnagel-Hohle, 1978). The adult will venture halting but comprehensible

sentences soon after arrival in the new language community while the 2-year-old

may at first lapse into silence. But in the long run the outcome is just the

reverse. After a few years, very small children speak the new language fluently

and soon sound just like natives. This is much less common in adults. This

point has been docu-mented in many studies. In one investigation, the

participants in the experiments were native Chinese and Korean speakers who

came to the United States (and became immersed in the English-language

community) at varying ages. These individuals were tested only after they had

been in the United States for at least 5 years, so they had had ample exposure

to English. And all of them were students and faculty members at a large

midwestern university, so they shared some social background (and presumably

were motivated to learn the new language so as to succeed in their university

roles).

In the test procedure, half of

the sentences the participants heard were grossly ungrammatical (e.g., The farmer bought two pig at the market; The

little boy is speak to apoliceman). The other half were the grammatical

counterparts of these same sentences.The participants’ task was to indicate

which sentences were grammatical in English and which were not. The results are

shown in Figure 10.36. Those who had been exposed to English before age seven

performed just like native speakers of English. Thereafter there was an

increasing decrement in performance as a function of age at first exposure. The

older the subjects when they first came to the United States, the less well

they acquired English (J. Johnson & Newport, 1989).

Recent experimentation confirms

that very young children acquire second languages at native levels, and adds

important detail about this process. Snedeker, Geren, and Shafto (2007)

followed the language learning progress of Chinese children adopted (at ages 2

to 6 years) by Americans. After adoption, these children were immersed in

monolingual English-language environments. Their English-language learning was

compared with that of American-born infants. Would the older Chinese-born

children learn differently (because they were more cognitively mature)? Or

would they learn in the same way as the infants (because all of them were

learning English from scratch)? The results show both effects: Just like infant

first-language learners, the adoptees learned nouns before verbs, and content

words before function words, suggesting that such words are easiest to learn

regardless of cognitive status of the learner. But the adoptees acquired

vocabulary at a faster rate, and so caught up to native-born age-mates after 18

months or so of being in the new language community

Finally, we can ask how the native and later-learned languages are distributed in the brain. It could be, for example, that the usual brain locus for language gets set up pre-cisely in the course of acquiring a first language and thereafter loses plasticity; as a result, the later-learned language must be shunted into new areas that are not special-ized for, or are secondary for, language. This would be another way of explaining why knowledge of the first language is generally so much better than knowledge of the sec-ond or third or fourth language learned. There is in fact accumulating evidence that the brain loci of late-learned languages usually are different from those of the first-learned language, a finding consistent with this suggestion. However, there are other possible interpretations of the same finding. Possibly the real cause of different loci for the two languages is the individual’s differential proficiency rather than the fact that one was learned before the other. One group of investigators supported this view by studying rare examples of people who learn a language in adulthood and become whizzes at it. Not surprisingly, many of these high-proficiency subjects were college instructors in modern language departments. The finding was that brain activity for both their lan-guages occurred in the same brain sites (Perani et al., 1998).

LATE EXPOSURE TO A FIRST LANGUAGE

These second-language learning

results lend some credence to the sensitive period hypothesis which, as earlier

noted, is also consistent with the differential language recovery of isolated

children (the cases of “Isabel” and “Genie”). However, there is an alternative

explanation. Possibly, second languages are rarely as well learned as first

languages because language habits ingrained with the first language interfere

with learning the second one (Seidenberg & Zevin, 2006). To distinguish

between the sen-sitive period hypothesis and such interference accounts, it

would be helpful to find individuals who acquired their first language at different ages. The best line of evidence in this

regard comes from American Sign Language (ASL). As we discussed earlier, many

congenitally deaf children have hearing parents who choose not to allow their

offspring access to ASL. Such children’s first exposure to ASL, therefore, may

be quite late in life when they first establish contact with the deaf

community. Because their hearing deficit did not permit them to learn the

spoken language of their caretakers either, such individuals are learning a

first (signed) language at an unusually late point in maturational time.

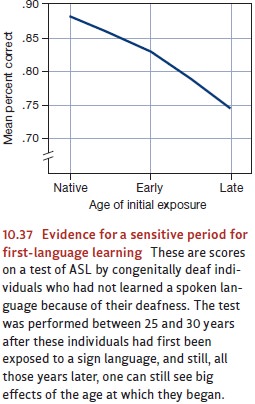

How does this late start

influence language learning? In one study, all of the partic-ipants had used

ASL as their sole means of communication for at least 25 years, guar-anteeing

that they were as expert in the language as they would ever become. Some of

them had been exposed to ASL from birth (because their parents were deaf

signers). Others had learned ASL between the ages of 4 and 6 years. A third

group had first come into contact with ASL after the age of 12.

Not surprisingly, all of these

signers were quite fluent in ASL, thanks to 25-plus years of use. But even so,

the age at first exposure had a strong effect (Figure 10.37). Those who had

learned ASL from birth used and understood all of its elaborations. Those whose

first exposure had come after the age of 4 years showed subtle deficits. Those

whose exposure began in adolescence or adulthood had much greater deficits, and

their use of function items was sporadic, irregular, and often incorrect

(Newport, 1990, 1999).

Related Topics