Chapter: Psychology: Language

Psychology Language: How We Understand

How We

Understand

How do listeners decipher the

drama of who-did-what-to-whom from the myriad com-plex and ambiguous sentence

forms in which this drama can be expressed? A major por-tion of the answer lies

in a complex, rapid, nonconscious processing system churning away to recover

the structure—and hence the semantic roles—as the speaker’s utterance arrives

word by word at the listener’s ear (Marcus, 2001; Savova et al., 2007;

Tanenhaus Trueswell, 2006). To get a hint of how this system operates, notice

first that the vari-ous function morphemes in speech help mark the boundaries

between phrases and propositions (for instance, but or and) and reveal

the roles of various content words even when their order changes. For instance,

when we reorder the phrases in a so-called

passive-voice sentence, we say, The cheese was eaten by the mouse

instead of The mouse atethe cheese.

The telltale morphemes -en and by cue the fact that the done-to rather

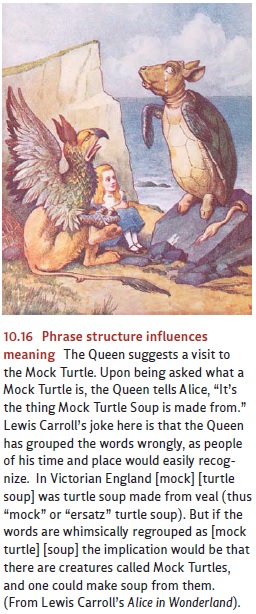

than thedo-er has become the subject (Bever, 1970). Sometimes the rhythmic

structure of speech (or the hyphen punctuation in written English) helps to

disambiguate the utterance, as in the distinction between a black bird-house and a black-bird

house (L. R. Gleitman & H. Gleitman, 1970; Snedeker & Trueswell,

2003; see Figure 10.16). Listeners also are sensi-tive to many clues from

background knowledge and plausibility that go beyond syntax to discern the real

communicative intents of speakers. We next discuss some examples of how these

kinds of clues work together to account for the remarkable speed and accuracy

of human language comprehension despite the apparent complexity and ambiguity

of the task that the listener faces.

THE FREQUENCY WITH WHICH THINGS HAPPEN

Often a listener’s interpretation

of a sentence is guided by background knowledge, knowledge that indicates the

wild implausibility of one interpretation of an otherwise ambiguous sentence

(G. Altmann & Steedman, 1988; Sedivy, Tanenhaus, Chambers, & Carlson,

1999). For example, no sane reader is in doubt over the punishment meted out to

the perpetrator after seeing the headline Drunk

Gets Six Months in Violin Case (Pinker, 1994). But in less extreme cases,

the correct interpretation is not immediately obvious. Most of us have had the

experience of being partway through hearing or reading a sen-tence and

realizing that somewhere we went wrong. For example, we may make a

word-grouping error, as in reading a sentence that begins The fat people eat . . . The natural inclination is to take the fat people as the subject noun

phrase and eat as the beginning of

the verb phrase (Bever, 1970). But suppose the sentence continues:

The fat people eat accumulates on their hips and thighs.

Now one must go back and reread.

(Notice that this sentence would have been much easier if, as is certainly

allowed in English, the author had placed the function word that before the word people: The fat that people eat accumulates

on their hips and thighs.) The partial misreading (or “mishearing” in the

case of spoken language) is termed a gardenpath

(in honor of the cliché phrase “led down the garden path,” in which someone

canbe deceived without noticing it). Because of the misleading content or

structure at the beginning of the sentence, the reader is enticed toward one

interpretation, but he must then retrace his mental footsteps to find a

grammatical and understandable alternative.

Psycholinguists have various ways

of detecting when people are experiencing a garden path during reading. One is

to use a device that records the motion of the reader’s eyes as they move

across a page of print. Slowdowns and visible regressions of these eye

move-ments tell us where and when the reader has gone wrong and is rereading

the passage (MacDonald, Pearlmutter, & Seidenberg, 1994; Rayner, Carlson,

& Frazier, 1983; Trueswell, Tanenhaus, & Garnsey, 1994). Using this

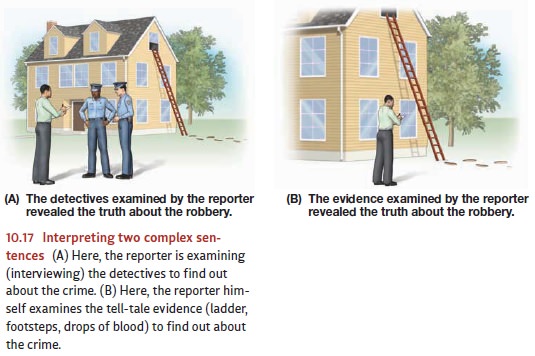

technique, one group of investigators looked at the effects of plausibility on

readers’ expectations of the structure they were encountering (see Figure

10.17). Suppose that the first three words of a test sentence are

The detectives examined . . .

Participants who read these words

typically assume that The detectives

is the subject of the sentence and that examined

is the main verb. They therefore expect the sentence to end with some noun

phrase—for example: the evidence. As

a result, they are thrown off track when they dart their eyes forward and

instead read that the sentence continues

. . . by the reporte.

The readers’ puzzlement is

evident in their eye movements: They pause and look back at the previous words,

obviously realizing that they need to revise their notion that examined was the main verb. After this

recalculation, they continue on, putting all of thepieces together in a new

way, and so grasp the entire sentence:

The detectives examined by the reporter revealed the truth about

the robbery.

The initial pause at by the reporter showed that readers had

been led down the gar-den path and now had to rethink what they were reading.

But what was it exactly that led the participants off course with this

sentence? Was the difficulty just that passive-voice sentences are less

frequent than active-voice sentences? To find out, the experi-menters also

presented sentences that began

The evidence examined by the reporter . . .

Now the participants experienced

little or no difficulty, and read blithely on as the sen-tence ended as it had

before (. . . revealed the truth about

the robbery). Why? After all, this sentence has exactly the same structure

as the one starting The detectives .

. . and so, apparently, the structure itself was not what caused the garden

path in this case. Instead, the difficulty seems to depend on the plausible

semantic relations among the words. The noun detectives is a “good subject” of verbs like examined because detectives often do examine things—such as

footprints in the garden, spots of blood on the snow, and so on. Therefore,

plausibility helps the reader to believe that the detectives in the test

sentence did the examining—thus leading the reader to the wrong interpretation.

Things go differently, though, when the sentence begins The evidence, because evidence, of course, is not capable of

examining anything. Instead, evidence is a likely object of someone’s examination, and so a participant who has read The evidence examined . . . is not a bit

surprised that the next word that comes up is by. This is the function mor-pheme that signals that a

passive-voice verb form is on its way—just what the reader expected given the

meanings of the first three words of the sentence (Trueswell & Tanenhaus,

1992).

It seems, then, that the process

of understanding makes use of word meanings and sentence structuring as mutual

guides. We use the meaning of each word (detectives

ver-sus evidence) to guide us toward

the intended structure, and we use the expected struc-ture (active versus

passive) to guess at the intended meanings of the words.

WHAT IS HAPPENING RIGHT NOW ?

Humans often talk about the

future, the past, and the altogether imaginary. We devour books on antebellum

societies that are now gone with the wind, and tales that speak of . . . a

Voldemort universe that we hope never to experience. But much of our

conversation is focused on more immediate concerns, and in these cases the

listener can often see what is being referred to and can witness the actions

being described in words. This sets up a two-way influence—with the language we

hear guiding how we perceive our surround-ings, and the surroundings in turn

shaping how we interpret the heard speech.

For example, in one experiment,

on viewing an array of four objects (a ball, a cake, a toy truck, and a toy

train), participants listening to the sentence Now I want you to eatsome cake turned their eyes toward the cake as

soon as they heard the verb eat (Altmann

Kamide, 1999) and before hearing cake.

After all, it was unlikely that the experi-menter would be requesting the

participants to ingest the toy train. In this case, the meaning of the verb eat focused listeners’ attention on only

certain aspects of the world in view—the edible aspects!

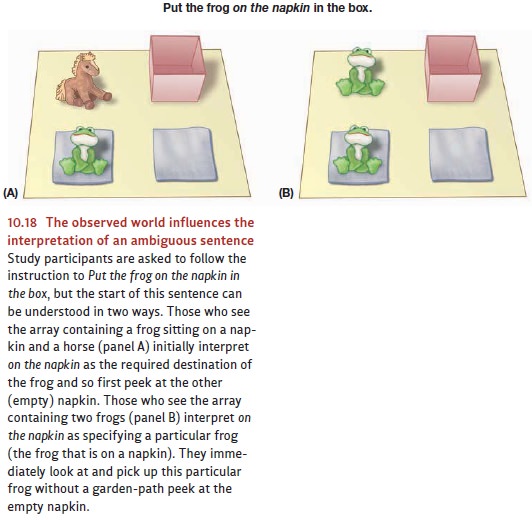

Just as powerful are the reverse

phenomena: effects of the visually observed world on how we interpret a

sentence (consider the array of toy objects in Figure 10.18A). These include a

beanie-bag frog sitting on a napkin and another napkin that has no toy on it.

When study participants look at such scenes and hear the instruction Put thefrog on the napkin into the box,

most of them experience a garden path, thinking (whenthey hear the first six

words) that on the napkin is the

destination where a frog should next be placed. After all, the empty napkin

seems a plausible destination for the frog. But three words later (upon hearing

into the box) they are forced to

realize that the intended destination is really the box and not the empty

napkin after all. This double-take reaction is evident in the participants’ eye

movements: On hearing napkin, they

look first to the empty napkin, and then look around the scene in confusion

when they hear into the box. Of

course, adult participants rapidly recover from this momentary boggle, and go

on to execute the instruction correctly, picking up the frog and putting it in

the box. But the tell-tale movement of the eyes has identified the temporary

mis-interpretation, a garden path.*

But now consider the array of

objects in Figure 10.18B. It differs from the array in Figure 10.18A, for now

there are two frogs, only one of which is on a napkin. This has a noticeable

effect on participants’ eye movements. Now, on hearing the same instruc-tion,

most of the participants immediately look to the frog that’s already on a

napkin when they hear napkin, and

they show no subsequent confusion on hearing into the box.

What caused the difference in

reaction? In the array of Figure 10.18A, with only one frog, a listener does

not expect the speaker to identify it further by saying the green frog or the frog to

the left or the frog on the napkin,

for there would be no point in doing so. Though such descriptions are true of

that particular frog, there is no need to say so— it is obvious which frog is

being discussed, because only one is in view. When the lis-tener hears on the napkin, therefore, she assumes

(falsely) that this is a destination, not a further specification of the frog.

Things are different, though,

with the array shown in Figure 10.18B. Now there is a risk of confusion about

which frog to move, and so listeners expect more information. In this two-frog

situation, therefore, the listener correctly assumes that on the napkin is the needed cue to the uniquely intended frog, and

so he does not wander down the mental garden path (Crain & Steedman, 1985;

Tanenhaus, Spivey-Knowlton, Eberhard, & Sedivy, 1995; Trueswell, Sekerina,

Hill, & Logrip, 1999).

CONVERSATIONAL INFERENCE : FILLING IN THE BLANKS

The actual words that pass back

and forth between people are merely hints about the thoughts that are being

conveyed. In fact, talking would take just about forever if speak-ers literally

had to say all, only, and exactly what they meant. It is crucial, therefore,

that the communicating pair take the utterance and its context as the basis for

making a series of complicated inferences about the meaning and intent of the

conversation (P. Brown & Dell, 1987; Grice, 1975; Noveck & Sperber,

2005; Papafragou, Massey, & Gleitman, 2006). For example, consider this

exchange:

·

Do you own a Cadillac?

·

I wouldn’t own any

American car.

Interpreted literally, Speaker B

is refusing to answer Speaker A’s yes/no question. But Speaker A will probably

understand the response more naturally, supplying a series of plausible

inferences that would explain how her query might have prompted B’s retort.

Speaker A’s interpretation might go something like this: “Speaker B knows that

I know that a Cadillac is an American car. He’s therefore telling me that he

does not own a Cadillac in a way that both responds to my question with a no and also tells me some-thing else:

that he dislikes all American cars.”

Such leaps from a speaker’s

utterance to a listener’s interpretation are commonplace. Listeners do not

usually wait for everything to be said explicitly. On the contrary, they often

supply a chain of inferred causes and effects that were not actually contained

in what the speaker said, but that nonetheless capture what was intended (H. H.

Clark, 1992).

LANGUAGE COMPREHENSION

We have seen that the process of

language comprehension is marvelously complex, influenced by syntax, semantics,

the extralinguistic context, and inferential activity, all guided by a spirit

of communicative cooperation. These many factors are uncon-sciously processed

and integrated “on line” as the speaker fires 14 or so phonemes (about 3 words,

on average) a second toward the listener’s ear. Indeed this immediate use of

all possible cues is what sometimes sends us down the garden path with false

and often hilarious temporary misunderstandings (Grodner & Gibson, 2005).

But in the usual case, the process of understanding would be too slow and

cumbersome to sustain conversation if the mind reacted to each sentence only at

its very end, after all possible information had been delivered, word by word, to

the ear. The mind thus makes a trade-off between rate and accuracy of

comprehension—the small risk of error is compensated for by the great gain in

speed of everyday understanding. When

we hear These missionaries are ready to eat or Will you join me in a bowl of soup, our common sense and language

skill combine in most cases to save us from drowning in confusion (Gibson,

2006). Most of the time we don’t even consciously register the various zany

interpretations that the language “theoretically” makes available for many

sentences (Altmann &Steedman, 1988; Carpenter, Miyake, & Just, 1995;

Dahan Tanenhaus, 2004; MacDonald, Pearlmutter, & Seidenberg, 1994;

Marslen-Wilson, 1975; Tanenhaus & Trueswell, 2006).

Related Topics