Chapter: Psychology: Language

Psychology Language: The Meanings of Sentences

The Meanings of

Sentences

Sentences have meanings too, over

and above the meanings of the words they contain. This is obvious from the fact

that two sentences can be composed of all and only the same words and yet be

meaningfully distinct. For example, The

giraffe bit the zebra and The zebra

bit the giraffe describe different events, a meaning difference of some

impor-tance, at least to the zebra and the giraffe.

The typical sentence introduces

some topic (the subject of the

sentence) and then makes some comment, or offerunderstand a sentence, then, is

to determine which actors are portraying the various roles and what the plot

(the action) is; that is, to decide on the basis of sentence structure who did

what to whom.

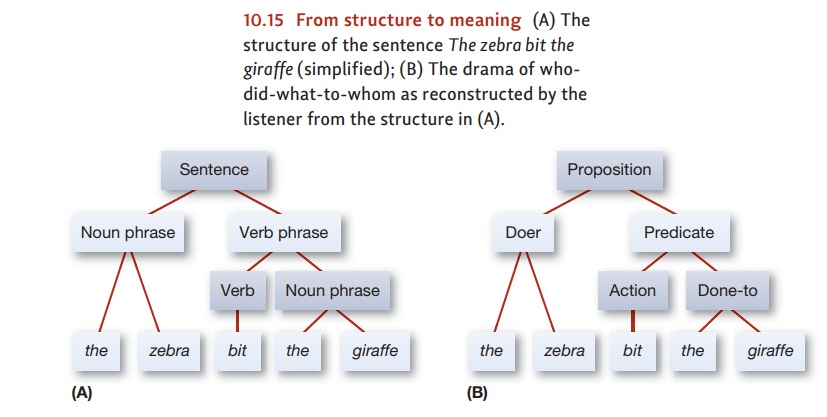

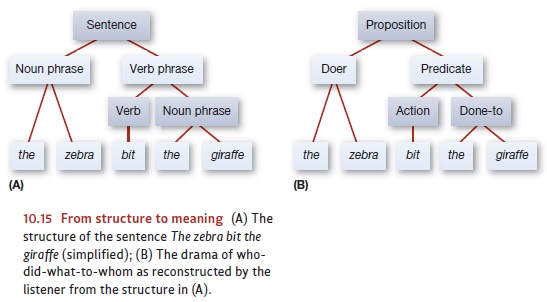

For the very simplest sentences

of a language, their grammatical structure links up rather directly to the

semantics of who-did-what-to-whom (M. C. Baker, 2001; Grimshaw, 1990;

Jackendoff, 2002). To get a feel for how this system works, see Figure 10.15A,

which shows the phrase structure of the zebra

sentence. We can “read” the semantic roles off of this syntactic tree by

attending to its geometry, as shown in Figure 10.15B. The doer of the action is

the noun phrase that branches directly from the root of the tree (a position

known as “the sentence subject,” namely, the

zebra). The “done-to” is the noun phrase that branches off of the verb

phrase (a position known as “the direct object,” namely, the giraffe). So different noun phrases in the syntactic struc-ture

have different semantic roles. More complex sentences of the language will

encode yet further semantic roles and relations, for example, The nanny (do-er) feeds (act) somesoup (done-to,

or thing affected) to the baby (recipient) with a spoon (instrument).

Summarizing, the position of the

words and phrases in this simple sentence of English is providing the semantic

role information to the listener. Serialization is of cen-tral importance in

this regard in English and many other languages. However, there is another type

of information, used in the English pronoun system, that can signal the

semantic roles without regard to serial position. For instance, the sentences He hadalways admired her intelligence andHer intelligence is what he had always

admired mean thesame thing. It is the particular form of a pronoun (he versus him, she versus her) that assigns the semantic roles in

this case. Many languages use something analogous to our pronoun system as the

primary means for signaling semantic roles, for nouns as well as pronouns. They

do this with case markers, which

usually occur as function morphemes. When case markers occur regularly in a

language, the word order itself can be much more flexible than it is in

English. In Finnish, for example, the words meaning zebra and giraffe change

their serial order in Seepra puri

kirahvia and Kirahvia puri seepra,

but in either order it is the giraffe (kirahvia)

who needs the medical attention. It is the suffix -a (rather than -ia) that

in both sentences identifies the zebra as the aggressor in this battle.

COMPLEX SENTENCE MEANINGS

In very simple sentences, as we

have seen, the phrase structure straightforwardly reflects the propositional

meaning of who-did-what-to-whom. But the sentences we encounter in everyday

conversation are usually much more complicated than these first examples. Many

factors contribute to complexity. Sometimes we reorder the phrases so as to

emphasize aspects of the scene other than the doer (It was the giraffe who got bittenby the zebra). Sometimes we wish

to question (Who bit the giraffe?) or

command (Bite that giraffe!) rather

than merely comment on the passing scene. And often we wish tos some

information, about that topic (the predicate).

Thus, when we say, The giraffe bit the

zebra, we introduce the giraffe as the topic, and then we propose or predicate of the giraffe that it bit the zebra. Accordingly,

sentence meanings are often called propositions.

In effect, a simple sentence describes a minia-ture drama in which the verb is

the action and the nouns are the performers, each playing a different semantic role. In The zebra bit the giraffe, the zebra plays the role of doer or

agent who causes or instigates the action, the giraffe is the done-to—the thing

affected by the action, and biting is the action itself. The job of a listener

who wants to express our attitudes (beliefs, hopes, and so forth) toward

certain events (I was delightedto hear

that the zebra bit the giraffe), or to relate one proposition to another,

and so willutter two or more of them in the same sentence (The zebrathat arrived from

Kenyabitthe giraffe). All this

added complexity of meaning is mirrored by corresponding com-plexities in the

sentence structures themselves.

Most ordinary language users

fluently utter, write, and understand many sentences 50, 100, or more morphemes

in length. The example below is from a blogger writing about ordering beauty

supplies on line—so we can hardly protest that it was the unusual creation of

some linguistic Einstein or literary giant:

However, I didn’t know how to order it and came across your site

where you found free trial supplies which is great because i dont want to pay

for something i didnt know worked

This author has managed to cram

nine verbs in four different tenses into an infor-mal but intricate grammatical

narrative. How did he or she manage to do it? Surely not by memorizing

superficial recipes like “an English sentence can end with two verbs in a row”

but rather by nonconsciously appreciating combinatorial regularities of

enor-mous generality and power that build up sentence units like acrobats’

pyramids. The complex sentences are constructed by reusing the same smallish

set of syntax rules that formed the simple sentences, but tying them all

together using function morphemes for the nails and glue (Chomsky, 1959, 1981a;

Z. Harris, 1951; Joshi, 2002).

AMBIGUITY IN WORDS AND SENTENCES

Not only do sentences often

become complex. Very often a sentence can be interpreted more than one way: It

is ambiguous. Sometimes, the ambiguity depends only on one word having two or

more meanings (that is, having more than one “entry” in our men-tal dictionaries);

examples can be seen in such newspaper headlines as Children’s StoolsUseful for Garden Work; Red Tape Holds up Bridge;

Prostitutes Appeal to Pope. In many cases,though, the ambiguity depends on

structure: in particular, on alternate ways that words are grouped together in

the syntactic tree (Police Are Ordered to

Stop Drinking on Campus;Oil Given Free to Customers in Glass Bottles).

There is a big difference, after all, betweenpolice who [stop drinking] [on

campus] and those who [stop] [drinking on campus].*

Such structural ambiguity is

pervasive in everyday speech and writing, even with short and apparently simple

sentences. For instance, Smoking

cigarettes can be dangerous could be a warning that to inhale smoke could

harm your health, or a warning that if you leave your butt smoldering in an

ashtray, your house might burn down.

Related Topics