Chapter: Psychology: Language

Building Blocks of Language: Phrases and Sentences

Phrases and

Sentences

Words and phrases now combine to

form sentences. Once again, at this new level of complexity, there are

constraints on the permitted sequences. House

the is red and Whereput you the

pepper? are ungrammatical—not in keeping with the regularities of form

thatcharacterize a particular language. One might at first glance think that

the grammaticality of a sentence is just a matter of meaningfulness—whether the

sequence of words has yielded a coherent idea or thought. But this is not so.

Some word sequences are easily interpretable, but still seem badly constructed

(That infant seemssleeping). Other

sequences are not interpretable, but seem well constructed even so(Colorless green ideas sleep peacefully).

This latter sequence makes no sense (ideas neither sleep nor are colorful;

green things are not colorless), and yet is well formed in a way that Sleep green peacefully ideas colorless

is not. Thus grammaticality depends not directly on meaning, but on conformance

with some rule-like system—patterns of sentence formation that are akin to

those of the rules of arithmetic or of chess. Much as you cannot (as a

competent calculator) add 2 and 2 to yield 5 or (as a competent chess player)

move a King two squares in any direction, you cannot put the noun before the

article (as in House the is red) to

yield a sentence in English. So, by analogy to chess, and so on, the patterns

describing how words and phrases can combine into sentences are called the “rules of grammar” or “syntax.”

We should emphasize that we have

not been speaking here about the “rules of proper English” imposed on groaning

children by school teachers and literary critics— rules forbidding the use of

“ain’t,” or of ending a sentence with a preposition. These lat-ter rules are

some people’s prescriptions for how

language should be (rather than how

itreally is), a matter that usually is based on which dialect of the

language has the mostprestige or social cachet (see Labov, 2007). In contrast,

the rules of syntax that we are discussing are the implicitly known

psychological principles that organize language use and understanding in all

humans, including very young children as well as adults, and members of

unschooled societies as well as professors of literature and CEOs of major

corporations.

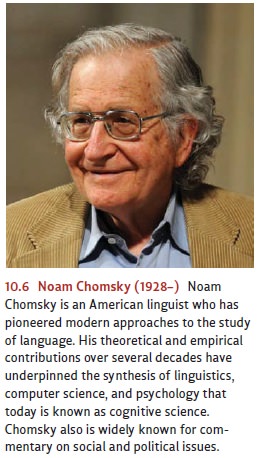

The study of syntax has been one

of the chief concerns of linguists and psycholin-guists, with much of the

discussion building from the theories of Noam Chomsky (Chomsky, 1965, 1995;

Figure 10.6). As Chomsky emphasized, this interest in the rules governing word

combination is not surprising if one wants to understand the fact that we can

say and understand a virtually unlimited number of new things, all of them “in

English.” We put our words together in ever new sentences to mean ever new things,

but we have to do so systematically or our listeners won’t be able to decipher

the new combinations.

THE BASICS OF SYNTACTIC ORGANIZATION

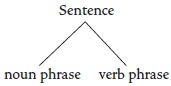

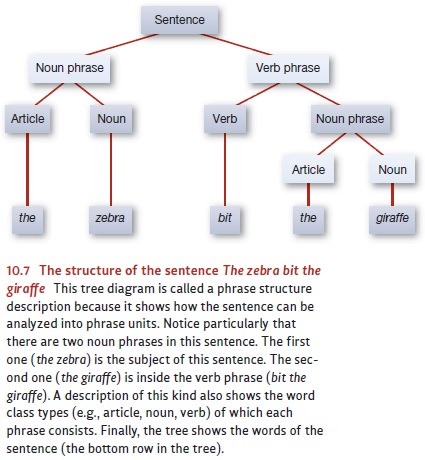

Consider the simple sentence The zebra bit the giraffe. It consists

of two major subparts or phrases, a noun phrase (the zebra) and a verb phrase (bit

the giraffe). Linguists depict this partitioning of the sentence by means

of a tree diagram, so called because

of its branching appearance:

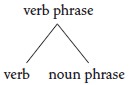

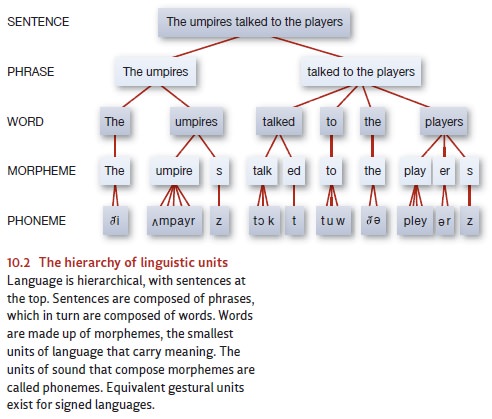

This notation is a useful way of

showing that individual sentences comprise a hierarchy of structures (as in

Figure 10.2). Each sentence can be broken down into phrases, and these phrases

into smaller phrases. Thus, our verb phrase redivides as a verb (bit) and a noun phrase (the giraffe).

These subphrases in turn break

down into the component words and morphemes. The descending branches of the

tree correspond to the smaller and smaller units of sentence structure. The

whole tree structure is called a phrase

structure description (shown as Figure 10.7).

The phrase structure description is a compact way of describing our implicit knowledge of how sentences are organized. Notice that recurrent labels in these trees reflect the fact that phrases are organized in the same way regardless of where they occur. For example, there are two instances of the label “noun phrase” in Figure 10.7. Each English noun phrase (except for pronouns and proper names) follows the same pattern whether it is at the start, middle, or end of a sentence: Articles such as a and the come first; any adjectives come next; then the noun. This patterning accounts for why anyone who rejects a sentence like The shirt green fit him well as a grammatical sentence of English is guaranteed also to reject Albert is wearing the shirt green and They bought theshirt green at Walmart on Thursday. In essence, then, phrase structure rules define groupsof words as modules that can be plugged in anywhere that the sentence calls for a phrase of the specified type. Other languages choose wholly or partly different orderings of words inside the phrase (e.g., French la chemise verte) and of phrases within the sentence, but they make their phrase structure choices just as regularly and systematically as does English.

Because the phrase structure of a

sentence is its fundamental organizing principle, anything that conforms to or

reveals this structure will aid the listener during the rapid process of

understanding a sentence, and anything that obscures or complicates the phrase

structure will make comprehension that much more difficult. To illustrate, one

investigator asked listeners to memorize strings of nonsense words that they

heard spo-ken. Some of the strings had no discernible structure at all, for

example, yig wur vum rixhom im jag miv.

Other strings also included various function morphemes, for example, the yigs wur vumly rixing hom im jagest miv.

One might think that sequences of the second typewould be harder than the first

to memorize, for they are longer. But the opposite is true. The function

morphemes allowed the listeners to organize the sequence as a phrase structure,

and these structured sequences were appreciably easier to remember and repeat

(W. Epstein, 1961). Figure 10.8 shows that phrase structure organization

facili-tates reading much as it does listening.

Related Topics