Chapter: Psychology: Language

Building Blocks of Language: The Sound Units

The Sound Units

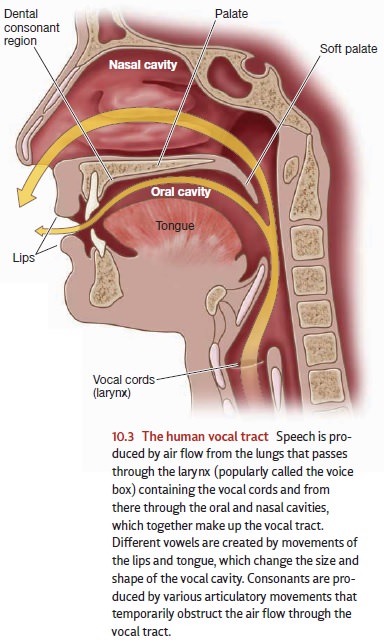

To speak, we force a column of

air up from the lungs and out through the mouth, while simultaneously moving

the various parts of the vocal apparatus from one position to another (Figure

10.3). Each of these movements shapes the column of moving air and thus changes

the sound produced. The human speech apparatus can emit hundreds of different

speech sounds clearly and reliably, but each language makes systematic use of

only a small number of these

physical possibilities. For example, consider the English word bus, which can be pronounced with more

or less of a hiss in the s. This

sound dif- ference, though audible, is irrelevant to the English-language

listener, who interprets what was heard to mean “a large vehicle” in either

case. But some sound distinctions do matter, for they signal differences in

meaning. Thus, neither butt nor fuss will be taken to mean “a large

vehi-cle.” This suggests that the distinctions among s, f, and t sounds are rel-evant to the perception

of English, while the difference in hiss duration is not. The sound categories

that matter in a language are called its phonemes.

English uses about 40 different phonemes.* Other lan-guages select their own

sets. For instance, German uses certain guttural sounds that are never heard in

English, and French uses some vowels that are different from the English ones,

making trouble for Americans who are trying to order le veau or le boeuf in

Parisian restaurants (Ladefoged & Maddieson, 1996; Poeppel & Hackl,

2007).

Not every phoneme sequence occurs

in every language. Sometimes these gaps are accidental. For instance, it just

so happens that there is no English word pilk.

But other gaps are systematic effects of the lan-guage design. As an

illustration, could a new breakfast food be called Pritos? How about Glitos

or Tlitos? Each of these would be a

new word in English, and all can be pronounced, but one seems wrong: Tlitos. English speakers sense that

English words never start with tl,

even though this phoneme sequence is perfectly acceptable in the middle of a

word (as in motley or battling). So the new breakfast food

will be marketed as tasty, crunchy Pritos

or Glitos. Either of these two names

will do, but Tlitos is out of the

question. The restriction againsttlbeginnings

is not a restriction onwhat human tongues and ears can do. For instance, one

Northwest Indian language is named Tlingit, obviously by people who are

perfectly willing to have words begin with tl.

This shows that the restriction is a fact about English specifically. Few of us

are con-scious of this pattern, but we have learned it and similar patterns

exceedingly well, and we honor them in our actual language use.

Languages differ from one another

in several other ways at the level of sound. There are marked differences in

the rhythm in which the successive syllables occur, and

differences as well in the use

and patterning of stress (or accent) and tone (or pitch). For instance, in

languages such as Mandarin Chinese or Igbo, two words that consist of the same

phoneme sequence, but that differ in tone, can mean entirely different things.

Languages also differ in how the phonemes can occur together within syllables.

Some languages, such as Hawaiian and Japanese, regularly alternate a single

consonant with a single vowel. Thus, we can recognize words like Toyota and origami as “sounding Japanese” when they come into common English

usage. In contrast, syllables with two or three consonants at their beginning

and end are common in English; for example, flasks

or strengths.

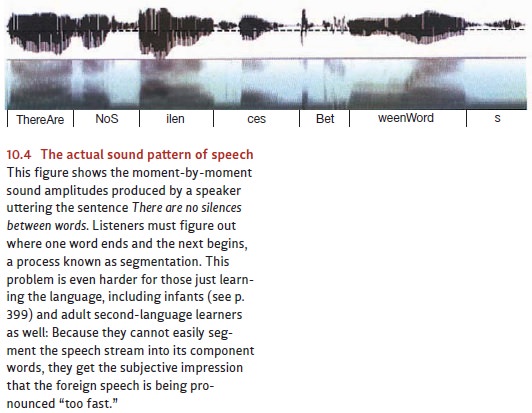

Speech can be understood at rates

of up to about 250 words per minute. The normal rate is closer to 180 words per

minute, which converts to about 15 phonemes per sec-ond. These phonemes are

usually fired off in a continuous stream, without gaps or silences in between

the words (Figure 10.4). This is true for phonemes within a single word and

also for words within a phrase, so that sometimes it is hard to know whether

one is hearing “that great abbey” versus “that gray tabby” or “The sky is

falling” versus “This guy is falling” (Levelt, 1989; Liberman, Cooper,

Shankweiler, & Studdert-Kennedy, 1967; see Figure 10.5).

Related Topics