Chapter: Psychology: Language

Language without a Model

Language

without a Model

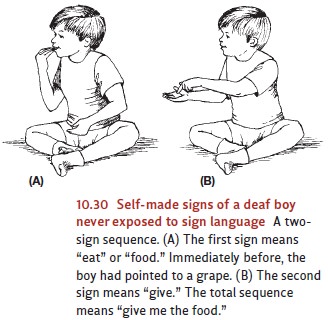

What if children of normal

mentality were raised in a loving and supportive environ-ment but not exposed

to either speech or signed language? Researchers found six children who were in

exactly this sort of situation (Feldman, Goldin-Meadow, & Gleitman, 1978;

Goldin-Meadow, 2000; Goldin-Meadow & Feldman, 1977). These children were

deaf, so they were unable to learn spoken language. Their parents were hearing

and did not know ASL. They had decided not to allow their children to learn a

gestural language, because they shared the belief (held by some educators) that

deaf children should focus their efforts on learning spoken language through

special train-ing in lip-reading and vocalization. This training often proceeds

slowly and has limited success, so for some time these children did not have any

usable access to spoken English. Not yet able to read lips, unable to hear, and

without exposure to a gestural language, these children were essentially

without any linguistic stimulation.

These language-isolated children

soon did something remarkable: They invented a language of their own. For a

start, the children invented a sizable number of gestures that were easily

understood by others. For example, they would flutter their fingers in a

downward motion to express snow, twist their fingers to express a twist-top

bottle,

and so on (Figure 10.30;

Goldin-Meadow, 2003). This spontaneously devel-oping communication system

showed many parallels to ordinary language learning. The children began to

gesture one sign at a time at approximately the same age that hearing children

begin to speak one word at a time, and they progressed to more complex

sentences in the next year or so. In these basic sentences, the deaf children

placed the individual gestures in a fixed serial order, according to semantic

role—again, just as hearing children do.

More recent evidence has shown

just how far deaf children can go in inventing a language if they are placed

into a social environment that favors their communicating with each other. In

Nicaragua until the early 1980s, (A)

deaf children from rural areas were widely scattered and usually knew no others

who were deaf. Based on the findings just mentioned, it was not surprising to

discover that all these deaf individuals developed homemade gestural systems

(“home signs”) to communicate with the hearing people around them, each system

varying from the others in an idiosyncratic way. But then a school was created

just for such deaf chil-dren in Nicaragua, and since then they have been bused

daily from all over the coun-tryside to attend it. Just as in the American and

many European cases, the school authorities have tried to teach these children

to lip-read and vocalize. But on the bus and in the lunchroom, and literally

behind the teachers’ backs, these children (age 4 to 14 in the initial group)

began to gesture to each other. Bit by bit their idiosyncratic home signs

converged on conventions that they all used, and the system grew more and more

elaborate (Figure 10.31; Senghas, Román, & Mavillapalli, 2006). The

emerging gestural language of this school has now been observed over three

genera-tions of youngsters, as new 4-year-olds arrive at the school every year.

These new members not only learn the system but also elaborate and improve on

it, with the effect that in the space of 30 years a language system of

considerable complexity and semantic sophistication has been invented and put

to communicative use by these children (Kegl, Senghas, & Coppola, 1999;

Senghas, Kita, and Özyürek, 2004). Perhaps it is true that Rome was not built

in a day, but for all we know, maybe Latin was! In sum, if children are denied

access to a human language, they go to the trou-ble to invent one for

themselves.

Related Topics