Chapter: Psychology: Motivation and Emotion

The Many Facets of Emotion

The Many Facets of Emotion

We

experience emotions such as

happiness, fear, sadness, pride, and anger when we consider our situation

(either real or imagined) to be relevant to our active personal goals (Scherer,

Schorr, & Johnstone, 2001). Some goals that make a situation meaning-ful

are of long-term concern, such as wanting to be liked. Other goals may be more

fleeting, such as hoping to get the last slice of cake, or rooting for the

underdog in a football match.

Whatever

the goal may be, once we’ve evaluated a situation as being personally

rele-vant, three types of changes are evident that, taken together,

characterize emotion. These changes affect our behavior (how we act), our

subjective experience (how we feel), and our physiology (how various systems in

the body are functioning) (Mauss, Levenson, McCarter, Wilhelm, & Gross,

2005). We can identify similar changes in the states we call moods, but psychologists distinguish

emotions from moods in several ways. For one, emotions typically have a clear

object or target (e.g., we are happy about something, or mad at someone); moods

do not. Emotions are also usually briefer than moods, lasting seconds or

minutes rather than hours or days.

BEHAVIORAL ASPECTS OF EMOTION

Some

of our bodily responses to emotion are quite general, such as a broad pattern

of approaching with interest in response to emotionally positive stimuli, or a

general withdrawal in response to emotionally negative stimuli. Perhaps the

most prominent behaviors associated with emotion, however, are our facial

behaviors—our smiles, frowns, laughs, gapes, grimaces, and snarls.

Charles

Darwin hypothesized that our facial expressions of emotion are actually

vestiges of our ancestors’ basic adaptive patterns (1872b). He argued, for

example, that our “anger” face, often expressed by lowered brows, widened eyes,

and open mouth with exposed teeth, reflects the facial movements our ancestors

would have made when biting an opponent. Similarly, our “disgust” face, often

manifested as a wrinkled nose and protruded lower lip and tongue, reflects the

way our ancestors responded to foul odors or spit out foods. (For elaborations,

see Ekman, 1980, 1984; Izard, 1977; Tomkins, 1963.)

In

support of this position, Darwin noted that our facial expressions resemble

many of the displays made by monkeys and apes. Darwin also believed that the

expressions would be identical among humans worldwide, even “those who have

associated but little with Europeans”. This point, too, can be confirmed—for

example, in observations of children born blind, who nonetheless express emotions

using the typical, recog-nizable set of facial expressions despite the fact

that they could not have learned these expressions through imitation (see, for

example, Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1970; Galati, Scherer, & Ricci-Bitti, 1997;

Goodenough, 1932).

A

different test of this universality claim involves comparisons between cultures

(Russell, 1994; Tracy & Robins, 2008), but only a tiny number of studies

have used the participants most crucial for this test: members of relatively

isolated non-Western cul-tures (Ekman, 1973; Ekman & Oster, 1979; Fridlund,

Ekman, & Oster, 1983; Izard, 1971). Why is this group crucial? If research

participants, no matter where they live, have been exposed to Western movies or

television, their responses might indicate only the impact of these media and

thus provide no proof of the universality claim. Therefore, we need

participants who have not seen reruns of Western soap operas, or Hollywood

movies, or a slew of Western advertising.

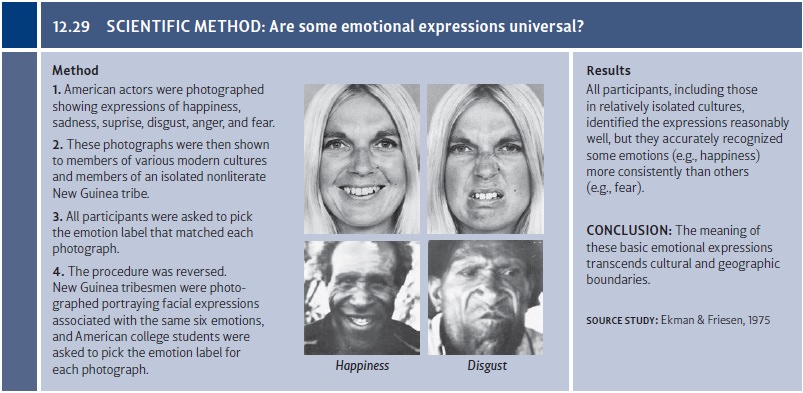

In

one of the few studies of this critical group, American actors were

photographed showing expressions that conveyed emotions such as happiness,

sadness, anger, and fear. These photographs were then shown to members of

various modern literate cultures (Swedes, Japanese, Kenyans) and to members of

an isolated nonliterate New Guinea tribe. All participants who saw the photos

were asked to

pick

the emotion label that

matched

each photograph. In other cases, the procedure was reversed. For example, the

New Guinea tribesmen were photographed portraying the facial expressions that

they considered appropriate to various situations, such as happiness at the

return of a friend, grief at the death of a child, and anger at the start of a

fight (Figure 12.29). American college students then looked at the photographs

and judged which situation the tribesmen in each photo had been asked to convey

(Ekman & Friesen, 1975).

In

these studies, all the participants, including those in relatively isolated

cultures, did reasonably well. They were able to supply the appropriate emotion

label for the pho-tographs, or to describe a situation that might have elicited

the expression shown in the photograph. But they were more successful at

recognizing some expressions than at recognizing others. We highlighted the

biological roots of smiling, and, in

fact, these were, in this study, generally matched with “happy” terms and

situations, with remarkable levels of consistency (Ekman, 1994; Izard, 1994;

see also Russell, 1994). Other emotions, such as disgust, were less well

recognized, but still identified at levels well above chance, suggesting that

the meaning of emotional expressions tran-scends cultural and geographic

boundaries.

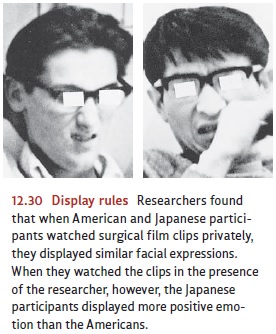

Let us note, though, that even though the perception of emotions may be similar in all cultures, the display of emotions is surely not. A widely cited example comes from research in which American and Japanese participants were presented with harrowing surgical films (Figure 12.30). Participants first watched the films privately (i.e., with no one in the room with them), but their facial expressions were recorded by a hidden camera. The facial reactions of Americans and Japanese were virtually identical. But when the participants then watched one of the films again while being interviewed by an experimenter, the results were quite different. In this context, the Japanese showed more positive emotion than the Americans showed (Ekman, 1972; Friesen, 1972). Thus, when in public, participants’ facial expressions were governed by the display rules set by their culture—deeply ingrained conventions, often obeyed without awareness, that govern the facial expressions considered appropriate in particular contexts (Ekman &Friesen, 1969; Ekman, Friesen, & O’Sullivan, 1988).

Of

course, display rules are not limited to a person’s reactions to a gruesome

film. Other studies have extended the analysis of display rules in contexts as

diverse as par- ticipating in sports (H. S. Friedman & Miller-Herringer,

1991) and receiving presents one does not like (P. M. Cole, 1985). Research has

also explored the way in which indi- viduals

differ in their

knowledge of display

rules (Matsumoto, Yoo, & Nakagawa, 2008). These differences include

variation not only from one person to the next, but also

between the genders.

For example, women

in Western cultures

are more likely to express their emotions than men are, particularly

emotions such as sadness (Brody & Hall, 2000; Kring & Gordon, 1998).

EXPERIENTIAL ASPECTS OF EMOTION

Along

with changes in our behavior, emotion also involves changes in how we feel.

Indeed, emotional experience has long been the essence of poetry, literature,

and other forms

of artistic expression

that are all

replete with expressions of

undying love, mortal hatred, and

unquenchable sadness. How can

we study these

fleeting and complex

feelings hidden inside

the mind (Barrett, Mesquita,

Ochsner, & Gross, 2007)? Here, as elsewhere, scientists begin by seeking a

proper classification scheme, and one proposal has focused on defining specific

categories of emotions (see, for example, R. S. Lazarus, 1991). One problem

with this approach, though, lies in

defining exactly what the

categories are. Common language gives few clues. There are over 550 emotion

words in

English (Averill, 1975), and many

more in other

languages that cannot

be translated readily into

English. However, as

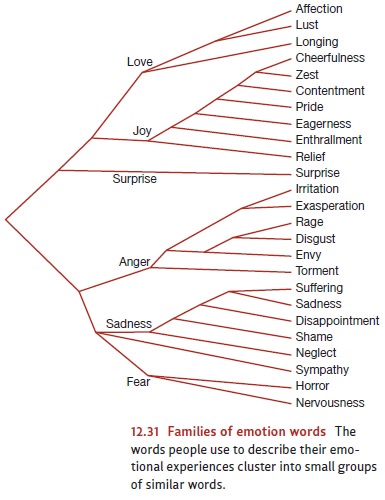

Phillip Shaver and

his colleagues have shown, people typically use emotion

words in ways that reveal a relatively small num- ber of “clusters,” which are

defined by words with similar meanings (Shaver, Schwartz, Kirson, &

O’Connor, 1987). As in Figure 12.31, one cluster involves words associated with

love, another involves words associated with joy, and other clusters describe anger,

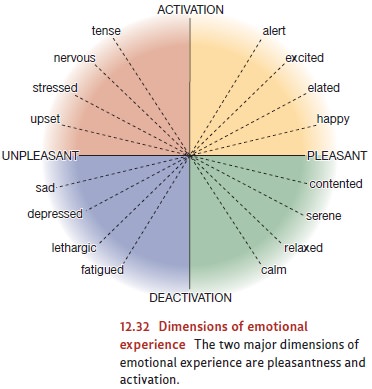

sadness, and fear. An alternative approach describes emotions in terms of

dimensions rather than categories: “more

this” or “less that” rather than “this type” versus “that type.”There are

various ways in which we might define these dimensions, but one relies simply

on how pleasant or unpleasant the emotion feels, and then how activated

the person feels

when in the

midst of the

emotion (Barrett, 1998; Larsen & Diener, 1992; Russell, 1980, 1983);

these two axes can be used to create a circle within which all the various

inter- mixtures of the dimensions can be described, as in Figure 12.32.

Either

of these categorization schemes can help us figure out how emotions relate to

one another—which are similar, which are sharply distinct. But neither scheme

really tells us what the emotions really feel

like, and so neither scheme answers

questions about individual or cul- tural

differences in emotional

experience. Does your happiness

feel the same as mine? When

someone in Paris feels triste, is

that person’s feeling the same as the

feeling of someone

in London who

feels sad, or

someone in Germany who feels traurig?

For

that matter, how should we think about cultures that have markedly different

terms for describing their emotions? The people who live on the Pacific Island

of Ifalik lack a word for “surprise,” and the Tahitians lack a word for

“sadness.” Likewise, other cultures

have words that

describe common emotions

for which we

have no special

terms.

The Ifaluk sometimes feel an emotion they call fago, which involves a complex mixture of compassion, love, and

sadness experi-enced in relationships in which one person is dependent on the

other (Lutz, 1986, 1988). And the Japanese report a common emotion called amae, which is a desire to be dependent

and cared for (Doi, 1973; Morsbach & Tyler, 1986). The German language

reserves the word Schadenfreude for

the special pleasure derived from another’s misfortune. Do people in these

cultures experience emotions that we do not (Figure 12.33)? Or are emotional

experiences common across cultures, despite the variations in cultures’ labels

for emotional expe-riences? On these difficult questions, the jury is still out.

PHYSIOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF EMOTION

When

we respond emotionally, it is often a whole body affair, and the bodily

reactions associated with different emotions certainly feel different from one another (Levenson, 1994). That is, not only

do the emotions differ in how they feel inside our “head,” but they also seem

to differ in how they feel in the rest of the body. The sick stomach and

wrinkled nose of disgust, for example, feel decidedly different from the

squared shoul-ders and puffed chest of pride. And anger’s hot head and coiled

muscles seem opposite fear’s cold feet and faint heart.

From

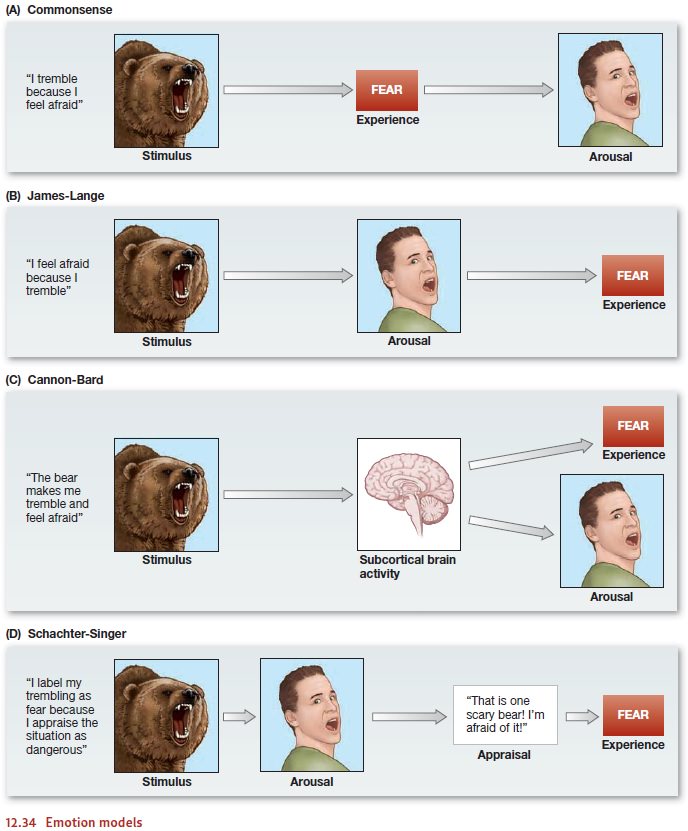

a common-sense perspective, it seems that emotions arise when we encounter a

significant stimulus, and this encounter leads to bodily changes that dif-fer

by emotion (Figure 12.34A). Interestingly, this sequence of events was turned

on its head by one of the first emotion theories in the field, namely, William

James’s the-ory that different emotions provoke different patterns of

physiological response (James, 1884). According to the James-Lange theory of emotion (Carl Lange was a European

contemporary of James’s who offered a similar account), the reason emo-tions

feel different from one another subjectively is that we sense the different

phys-iological patterns produced by each emotion. Specifically, this view holds

that emotion begins when we perceive a situation of an appropriate sort—we see

the bear or hear the insult. But our perception of these events is, as James

put it, “purely cog-nitive in form, pale, colorless, destitute of emotional

warmth”. What turns this perception into genuine emotion is our awareness of

the bodily changes produced by the arousing stimuli. These changes might

consist of skeletal movements (running) or visceral reactions (pounding

heartbeat), but only when we detect the biological changes do we move from cold

appraisal to emotional feeling, from mere assessment to genuine affect (Figure

12.34B). Moreover, the claim is that the specific

character of the biological changes is crucial—so that we feel fear because

we are experiencing the pattern of bodily changes associated with fear; we feel

hap-piness because of its pattern of changes in the body, and so on.

Subsequent theories, however, made quite different predictions about the degree of physiological patterning we should expect in emotion. For example, Walter Cannon, whom we met earlier as a pioneer in the study of the “fight or flight” response, believed that our physiological responses are quite general (W. B. Cannon, 1927). According to the Cannon-Bard theory of emotion (Philip Bard was a contem-porary of Cannon’s who espoused a similar view), it’s not easy to distinguish the bodily changes associated with different emotions, so that the bodily changes associated with anger are actually rather similar to the changes associated with happy excitement (Figure 12.34C).

Cannon’s

view gained support from early studies in which participants received

injections of epinephrine, which triggered broad sympathetic activation with

all its consequences—nervousness, palpitations, flushing, tremors, and sweaty

palms. These biological effects are similar to those that accompany fear and

rage, and so, according to the James-Lange theory, people detecting these

effects in their bodies should experience these emotions. But that was not the

case. Some of the participants who received the injections simply reported the

physical symptoms. Others said they felt “as if ” they were angry or afraid, a

kind of “cold emotion,” not the real thing (Landis & Hunt, 1932; Marañon,

1924). Apparently, the visceral reactions induced by the stimulant were by

themselves not sufficient to produce emotional experience.

Even

so, there is an obvious challenge to the Cannon-Bard theory. If different

emo-tions produce comparable physiological responses, then why do we have the

subjective impression that our bodies are doing quite different things in

different emotional states? This question was addressed by the Schachter-Singer theory of emotion

(Figure 12.34D). According to this theory, behavior and physiology are (as

James proposed) cru-cial for emotional experience. James was wrong, though, in

claiming that the mere per-ception of these bodily changes is sufficient to

produce emotional experience. That is because, in addition, emotion depends on

a person’s judgments about why her

body and physiology have changed (Schachter & Singer, 1962).

In

a classic study supporting this theory, participants were injected with a drug

that they believed was a vitamin supplement but really was the stimulant

epinephrine. After the drug was administered, participants sat in the waiting

room for what they thought was to be a test of their vision. In the waiting

room with them was a confederate of

the experimenter (someone who appeared to be another research participant but

was actu-ally part of the research team). In one condition the confederate

acted irritable, made angry remarks, and eventually stormed out of the room. In

another condition he acted exuberant, throwing paper planes out the window and

playing basketball with balled-up paper. Of course, his behavior was all part

of the experiment; the vision test that the participants were expecting never

took place (Schachter & Singer, 1962). Participants exposed to the euphoric

confederate reported feeling happy, and, to a lesser degree, par-ticipants

exposed to the angry confederate reported that they felt angry. Although this study

has come under criticism (G. D. Marshall & Zimbardo, 1979; Mezzacappa,

Katkin, & Palmer, 1999; Reisenzein, 1983), it remains influential because

it is a reminder that bodily arousal only partially determines the emotion that

is experienced.

Over

the past 50 years, researchers have tried to clarify how the body responds

dur-ing emotional experiences. One of the most interesting conclusions from

this research is that our perceptions of bodily differences among the emotions

may in some cases be illusions, compelling experiences that are not well

grounded in reality (Cacioppo, Berntson, & Klein, 1992). It seems,

therefore, that the various emotions are surprisingly similar if we examine the

body’s response “from the neck down.”

Even

so, the emotions are distinguishable biologically—in the pattern of brainactivation associated with each

emotion. Evidence on this point comes from studiesin the field of affective neuroscience (R . J. Davidson

& Sutton, 1995; Panksepp, 1991, 1998), whose proponents argue that emotions

arise not in one, but in multiple neu-ral circuits. Some brain regions are

activated in virtually all emotions (Murphy, Nimmo-Smith, & Lawrence, 2003;

Phan, Wager, Taylor, & Liberzon, 2002)—for example, the medial prefrontal

cortex. One likely possibility is that this section of the brain plays a

general role in attention and meaning analysis related to emotion. Other brain

regions, however, seem to be related to specific emotions. For example, fear is

often associated with activation of the amygdala, and sadness is often

associ-ated with activation of the cingulate cortex just below the corpus

callosum (although activation in these brain regions is not specific to these

emotions; see Barrett & Wager, 2006). Many researchers are convinced that

brain data like these will eventu-ally allow us to determine the extent to

which different emotions have different phys-iological profiles.

Related Topics