Chapter: Psychology: Motivation and Emotion

Cultural and Cognitive Aspects of Sexuality

Cultural and Cognitive Aspects of Sexuality

As

we have seen, our sexual behavior clearly has powerful physiological bases. At

the same time, it also has substantial cultural and cognitive components. In

this section, we consider proximal situational determinants of sexual behavior

as well as more remote evolutionary determinants of mate choice.

SITUATIONAL DETERMINANTS OF SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

Sex

is everywhere—in billboard advertisements, on television, in movies, and in

supermarket tabloids (Figure 12.20). Do these sexually charged images encourage

sexual feelings and behaviors? Or do they give vent to our sexual desires and

thereby decrease our sexual behavior?

Laboratory

studies find that men typically report greater sexual arousal in response to

sexually explicit materials than women do (Gardos & Mosher, 1999). However,

this finding may in part reflect the fact that most sexually explicit materials

are developed to appeal to men rather than to women. When researchers presented

sexually explicit films that were chosen by women, there were no gender

differences in response to the films (Janssen, Carpenter, & Graham, 2003).

Does

this arousal actually encourage sexual behavior? Findings on this point have

been mixed, but it appears that exposure to such material does, for at least a

few hours, increase the likelihood of engaging in sexual behavior (Both,

Spiering, Everaerd, & Laan, 2004). Much more concerning, however, have been

findings from studies of the effects of sexually explicit material on sexual

attitudes. In one study, Zillmann and Bryant (1988) found that viewing sexually

explicit films made participants less satisfied with their partner’s appearance

and sexual performance. Far more troubling, films of women being sexually

coerced increased male participants’ willingness to harm women (Zillman, 1989).

In short, then, pornography may have a small effect in encouraging sexual

behavior, but it may have a larger effect on perceptions, and, worst of all, violent pornography has a more powerful

effect in encouraging sexual aggression.

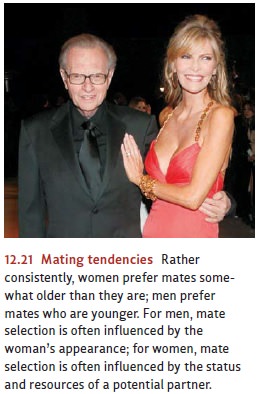

MATE CHOICE

In

most cultures in the modern world, both men and women are selective in choosing

their sexual partners, and mating usually happens only when both partners

consent. However, the sexes differ in

the criteria they use in making their choices (Figure 12.21). According to a

number of surveys, the physical attractiveness of the partner seems more

important to men than to women, while the social and financial status of the

partner matters more to women than it does to men. It also appears that men

generally prefer younger women, whereas women prefer older men. The data also

indicate that all of these male-female differences are found in many countries,

including the United States, China, India, France, Nigeria, and Iran (D. M.

Buss, 1989, 1992; D. M. Buss & Barnes, 1986).

How

should we think about all of these points? In earily, we looked closely at the

evolutionary account: An attractive woman is likely to be healthy and fertile,

so a male selecting an attractive partner would increase his chances of

reproductive success. Likewise, a younger woman will have more reproductive

years ahead of her, so a male choosing a younger partner could plausibly look

forward to more offspring. Any male selecting his mates based on their youth and

beauty would be more likely than other males to have many healthy offspring to

pass along his genes. Thus, through the process of natural selection these

preferences eventually would become widespread among the males of our species.

The

female’s preferences are also sensible from an evolutionary perspective.

Because of her high investment in each child (at the least, 9 months of

carrying the baby in her womb, and then months of nursing), she can maximize

the chance of passing along her genes to future generations by having just a

few offspring and doing all she can to ensure the survival of each. A wealthy,

high-status mate would help her reach this goal, because he would be able to

provide the food and other resources their children need. Thus, there would be

a reproductive advantage associated with a preference for such a male, and so a

gradual evolution toward all females in the species having this preference

(Bjorklund & Shackelford, 1999; Buss, 1992; Schmitt, 2005).

We

also noted that cultural factors play an important role. For example, in many

cultures human females only come to prefer wealthy, high-status males because

the females have learned, across their lifetimes, the social and economic

advantages they will gain from such a mate. In these cultures, women soon learn

that their profes-sional and educational opportunities are limited, and so

“marrying wealth” is their best strategy for gathering resources for themselves

and their young.

The

importance of culture becomes clear when we consider cultures that provide more

opportunities for women. In these cultures, “marrying wealth” is not a woman’s

only chance for economic and social security, so a potential husband’s

resources become correspondingly less important in mate selection. Various studies

confirm this predic-tion and show that in cultures that afford women more

opportunities, women attach less priority to a male’s social and economic

status (Kasser & Sharma, 1999; also see Baumeister & Vohs, 2004;

Buller, 2005; Eagly & Wood, 1999; W. Wood & Eagly, 2002).

In

short, there seems to be considerable consistency in mating preferences and a

contrast between the criteria males and females typically use. This consistency

has been documented in many cultures and across several generations. But there

are also varia-tions in mate-selection preferences that are clearly

attributable to the cultural context. These data clearly illustrate the

interplay of biological and cultural factors that governs our motivational and

emotional states.

Related Topics