Chapter: Psychology: Motivation and Emotion

Obesity

Obesity

The

physiological and cognitive mechanisms regulating an organism’s food intake

work remarkably well—but not perfectly. We see this in the fact that organisms

(humans in particular!) can end up either weighing far more than is healthy for

them or weighing too little. In some cases, the person is underweight

because—tragically—poverty and malnutrition are common problems in many parts

of the world (including nations that we would otherwise consider relatively

wealthy). Even when food is available, though, people can end up underweight.

Here, we deal with the more common problem in the Western world: obesity, a

problem so widespread that the World Health Organization has classified obesity

as a global epidemic (Ravussin & Bouchard, 2000).

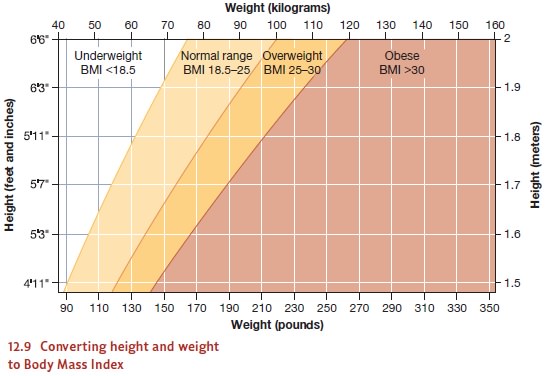

Obesity

is sometimes defined as a body weight that exceeds the average for a given

height by 20%. More commonly, though, researchers use a definition cast in

terms of the Body Mass Index (BMI),

defined as someone’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of his height in

meters (Figure 12.9). A BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 is considered normal. A BMI

between 25 and 30 counts as overweight, and a BMI of 30 or more is considered

obese. A BMI over 40 defines morbid

obesity—the level of obesity at which someone’s health is genuinely at

risk. For most people, morbid obesity means a weight roughly 100 pounds (45.3

kg) beyond their ideal.

THE GENETICROOTS OF OBESITY

Why

do people become obese? The simplest hypothesis is that some people eat too

much. In this view, obesity might be understood as the end result of

self-indulgence, or perhaps the consequence of an inability to resist temptation.

This hypothesis makes it seem like people could be blamed for their obesity,

like the condition is, in essence, their own fault. Such a view of obesity,

however, is almost certainly a mistake, because it ignores the powerful forces

that can put someone on the path toward obesity in the first place. Although

people do have considerable control over what and how much they eat, the

evidence suggests that some people are strongly genetically predisposed toward

obesity.

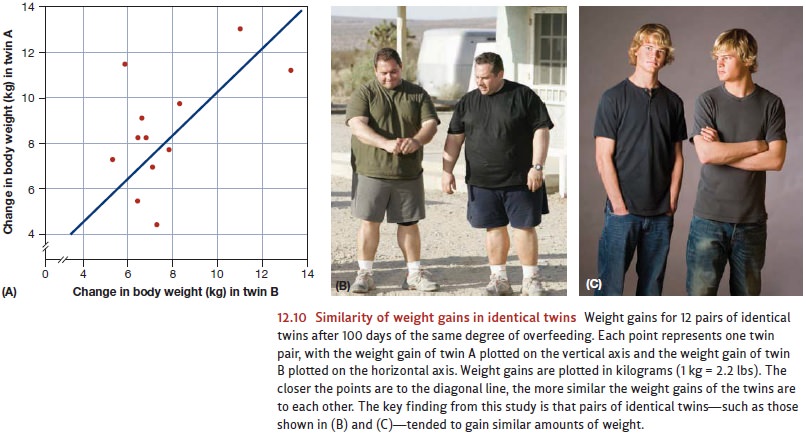

One

long-term study examined 12 pairs of male identical twins. Each of these men

ate about 1,000 calories per day above the amount required to maintain his

initial weight. The activities of each participant were kept as close to

equivalent as possible, and there was very little exercise. This regimen

continued for 100 days. Needless to say, all 24 men gained weight, but the

amounts they gained varied substantially, from about 10 to 30 pounds. The men

also differed in terms of where on their bodies the weight was deposited. For

some participants, it was the abdomen; for others, it was the thighs and

buttocks. Crucially, though, the amount each person gained was statistically

related to the weight gain of his twin (Figure 12.10). The twins also tended to

deposit the weight in the same place. If one developed a prominent paunch, so

did his twin; if another deposited the fat in his thighs, his twin did, too

(Bouchard, Lykken, McGue, Segal, & Tellegen, 1990; also see Herbert et al.,

2006).

It

seems, therefore, that the tendency to turn extra calories into fat has a

genetic basis. In fact, several mechanisms may be involved in this pattern, so

that, in the end, obesity can arise from a variety of causes. For example, some

people seem to be less sen-sitive to the appetite-reducing signals from leptin

and thus are more vulnerable to the effects of appetite stimulants such as NPY

(J. Friedman, 2003). For these people, a

tendency

to overeat may be genetically rooted. In addition, people differ in the

effi-ciency of their digestive apparatus, with some people simply extracting

more calories from any given food. People also differ in their overall

metabolic level; if, as a result, less nutrient fuel is burned up, then more is

stored as fat (Astrup, 2000; also M. I. Friedman, 1990a, b; Sims, 1986).

Given

these various mechanisms, should we perhaps think about obesity as some sort of

genetic defect, a biologically rooted

condition that leads to substantial health risk? Proponents of the “thrifty

gene” hypothesis emphatically reject this suggestion. They note that our

ancestors lived in times when food supplies were unpredictable and food

shortages were common, so natural selection may have favored individuals who

had especially inefficient metabolisms and, as a result, stored more fat. These

individu-als would have been better prepared for lean times and thus may have

had a survival advantage. As a result, the genes leading to this fat storage

might have been assets, not defects (J. Friedman, 2003; Fujimoto et al., 1995;

Groop & Tuomi, 1997; Ravussin, 1994).

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS AND OBESITY

Clearly,

then, “thrifty genes” might have helped our ancestors to maintain a healthy

body weight, but our ancestors lived in a time in which food was scarce. The

same genes will have a different outcome in modern times—especially for people

living in an afflu-ent culture in which a quick trip to the supermarket provides

all the calories one wishes. In this modern context, the “thrifty genes” can

lead to levels of obesity that create seri-ous health problems.

Whether

for genetic reasons, though, or otherwise, the evidence is clear that obesity

rates are climbing across the globe. In the United States, roughly 23% of the

population in 1991 was obese; more recent estimates of the rate—30%—are

appreciably higher (J. Friedman, 2003). Similar patterns are evident in other

countries. Over the last 10 years, for example, the obesity rates in most

European countries have increased by at least 10%, and, in some countries, by

as much as 40%. These shifts cannot reflect changes in the human genome;

genetic changes proceed at a much slower pace. Instead, the increase has to be understood

in terms of changes in diet and activity level—with people consuming more

calorically dense, high-fat foods and living a lifestyle that causes them to

expend relatively few calories in their daily routines.

This

increase in obesity rates is associated with increased rates of many health

problems, including heart attack, stroke, Type 2 diabetes, and some types of

cancer. The debate continues over the severity of these risks for people with

moderate levels of obesity—e.g., a BMI between 30 and 40 (Couzin, 2005; Yan et

al., 2006). There is no debate, however, about the health risks of so-called

morbid obesity (a BMI of 40 or higher), and this makes the worldwide statistics

on obesity a serious concern for health professionals.

Related Topics