Chapter: Psychology: Motivation and Emotion

Cultural and Cognitive Aspects of Threat and Aggression

Cultural and Cognitive Aspects of Threat and Aggression

In

many cases, humans (just like other animals) become aggressive in an effort to

secure or defend resources. This is evident in the wars that have grown out of

national disagreements about who owns a particular expanse of territory; on a

smaller scale, it is evident when two drivers come to blows over a parking

space. Humans also become aggressive for reasons that hinge on symbolic

concerns, such as insults to honor or objections to another person’s beliefs or

behavior. The latter type of aggression is clear in many of the hateful acts

associated with stereotyping. It is also a powerful contribu-tor to the

conflict among ethnic groups or people of different religions.

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES INAGGRESSION

Whatever

the source of the aggression, it is obvious that people vary enormously in how

aggressive they are (Figure 12.15). Some of us respond to provocation with

violence. Some turn the other cheek. Some find nonviolent means of asserting

themselves. What determines how someone responds?

For

many years, investigators believed that aggression was more likely in people

with relatively low self-esteem, on the argument that such individuals were

particularly vulnerable to insult and also likely to have few other means of

responding. More recent work, however, suggests that the opposite is the case,

that social provocations are more likely to inspire aggression if the person

provoked has unrealistically high self-esteem (Baumeister, 2001; Bushman &

Baumeister, 2002). Such a person is particularly likely to perceive the

provocation as a grievous assault, challenging his inflated self-image; in many

cases, violence will be the result.

Other personality traits are also relevant to aggression, including a factor called sensation seeking, a tendency to seek out varied and novel experiences in their daily lives. High levels of sensation seeking are associated with aggressiveness, and so are high scores on tests that measure the trait of impulsivity, a tendency to act without reflecting on one’s actions (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Joireman, Anderson, & Strathman, 2003).

In

addition, whether someone turns to aggression or not is influenced heavily by

the culture in which he was raised. Some cultures explicitly eschew violence;

this is true, for example, in communities of Quakers. But other cultures

prescribe violence, often via rules of chivalry and honor that demand certain

responses to certain insults. Gang violence in many U.S. cities can be

understood partly in this way, as can some of the fighting among the warlords

of Somalia. Cultural differences are also evident when we compare different

regions within the United States; for example, the homicide rate in the South

is reliably higher than in the North, and statistical evidence suggests that

this contrast is best attributed to social differences and not to factors like

population den-sity, economic conditions, or climate (Nisbett & Cohen,

1996).

How

exactly does culture encourage or discourage aggression? The answer in some

cases involves explicit teaching—when, for example, our parents tell us not to

be aggressive, or they punish us for some aggressive act. In other cases, the

learning involves picking up subtle cues that tell us, for example, whether our

friends think that aggression is acceptable, or repugnant, or cool. In still

other cases, the learning is of a different sort and involves what we called observational learning. This is learning

in which the people around us model through their own actions how one should

handle situations that might provoke aggression.

We

noted, though, that observational learning can also proceed on a much larger

scale, thanks to the societal influences that we are all exposed to. Consider

the violence portrayed on television and in movies. On some accounts, prime-time

tel-evision programs contain an average of five violent acts per hour, as

characters punch, shoot, and sometimes murder each other (Figure 12.16).

Overall, investigators estimate that the average American child observes more

than 10,000 acts of TV violence every year (e.g., Anderson & Bushman,

2001).

Evidence

that this media violence promotes violence in the viewer comes from studies of

violence levels within a community before and after television was introduced,

or before and after the broadcast of particularly gruesome footage of murders

or assassinations. These studies consistently show that assault and homicide

rates increase after such expo-sures (Centerwall, 1989; Joy, Kimball, &

Zabrack, 1986). Other studies indicate that chil-dren who are not particularly

aggressive become more so after viewing TV violence (e.g., Huesmann,

Lagerspetz, & Eron, 1984; Huesmann & Miller, 1994; for related data

show-ing the effects of playing violent video games, see Carnagey &

Anderson, 2005).

These

studies leave little doubt that there is a strong correlation, such that those

who view violence are more likely than other people to be violent themselves.

But does this correlation reveal a cause-and-effect relationship, in which the

viewing can actually cause someone to be more violent? Many investigators

believe it can (Anderson & Bushman, 2001, 2002; Bushman & Anderson,

2009; Carnagey, Anderson, & Bartholow, 2007; Cassel & Bernstein, 2007).

Indeed, the evidence persuaded six major professional societies (including the

American Psychological Association, the American Medical Association, and the

American Psychiatric Association) to issue a joint statement noting that

studies “point overwhelmingly to a causal connec-tion between media violence

and aggressive behavior in some children” (Joint Statement, 2000).

LIMITING AGGRESSION

Whether motivated by a wish to defend a territory or a desire to repay an insult, aggres-sion is costly. If we focus just on the biological costs to the combatants, aggression is dangerous and can lead to injury or death. For some species, and for some forms of vio-lence, these costs are simply the price of certain advantages—for survival or for repro-duction (e.g., Pennisi, 2005). Even so, natural selection has consistently favored ways of limiting the damage done by aggression.

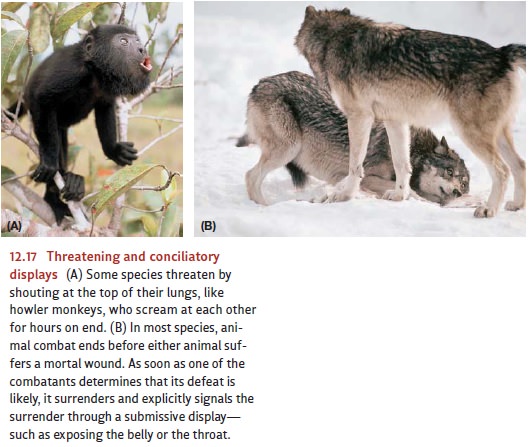

One

way that natural selection seems to have done this is by ensuring that animals

are keenly sensitive to the strength of their enemies. If the enemy seems much

stronger (or more agile or better armed or armored) than oneself, the best bet

is to concede defeat quickly, or better yet, never to start the battle at all.

Animals therefore use a vari-ety of strategies to proclaim their strength, with

a goal of winning the battle before it starts. They roar, they puff themselves

up, and they offer all sorts of threats, all with the aim of appearing as

powerful as they possibly can (Figure 12.17A). Conversely, once an animal

determines that it is the weaker one and likely to lose a battle, it uses a

variety of strategies for avoiding a bloody defeat, usually involving specific

conciliatory signals, such as crouching or exposing one’s belly (Figure

12.17B).

Similar

mechanisms are evident in humans. For example, the participants in a bar fight

or a schoolyard tussle try to puff themselves up to intimidate their opponents,

just as a moose or a mouse would. Likewise, we humans have a range of

conciliatory gestures we use to avoid combat—body postures and words of appeasement.

All

of these mechanisms, however, apply largely to face-to-face combat; sad to say,

these biologically based controls have little effect on the long-distance,

large-scale aggression that our species often engages in. As a result, battles

between nations will probably not be avoided by political leaders roaring or

thumping their chests; soldiers operating a missile-launcher cannot see (much

less respond to) their targets’ concilia-tory body posture. Our best hope for

reducing human aggression, therefore, is that the human capacity for moral and

intellectual reflection will pull us away from combat, and that considering the

cruelty and destruction of violence will lead us to reconcile our differences

by other means.

Related Topics